The 15 Best Games Since 2000, Number 9: BioShock

A brilliant combination of influences that bucked the trends of era and genre to stand as something wholly unique.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

We're currently in the middle of our daily countdown of the 15 Best Games Since 2000. Want to read more? Check out the rest of the entries here.

As a shooter, Irrational Games' 2007 hit BioShock was merely OK. It did its job, sure, but the speed and mechanics felt downright atavistic next to its FPS contemporaries from that same year, such as Call of Duty: Modern Warfare and Halo 3.

The answer, of course, is not to approach BioShock as a shooter. Yes, that may have been the genre into which it's most easily categorized, but the idea of hard and fast genres for games has grown increasingly obsolete these days. BioShock wasn't quite an RPG, and it wasn't quite an adventure game, but neither did it feel entirely like an FPS. It used shooting mechanics, the look and feel of '90s "Doom Clones," to accomplish something different than simply popping headshots — something more ambitious.

Admittedly, it was perhaps less ambitious than some would have preferred. BioShock, as the name suggests, came about as a sort of spiritual successor to Looking Glass Studios' PC classic System Shock, which in 1994 boldly bent FPS rules in order to squeeze in a narrative, RPG elements, and an adventure game-like inventory system. System Shock, in turn, had descended from Ultima Underworld, which had been a first-person dungeon crawler RPG that broke free of the format's traditional grid to become something like a proto-FPS. BioShock had deep roots, and in many ways its debut alongside Halo 3 seemed fitting: Just as Halo played like a technically amped-up but conceptually streamlined rendition of the Marathon games, BioShock felt like System Shock with the systemic depth replaced by more immersive graphics.

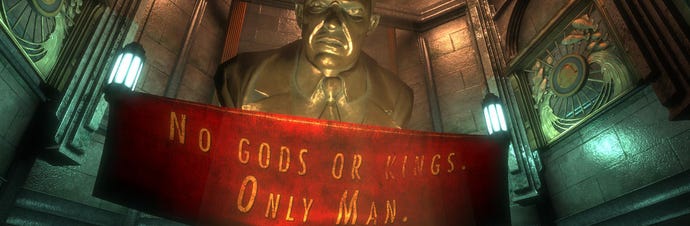

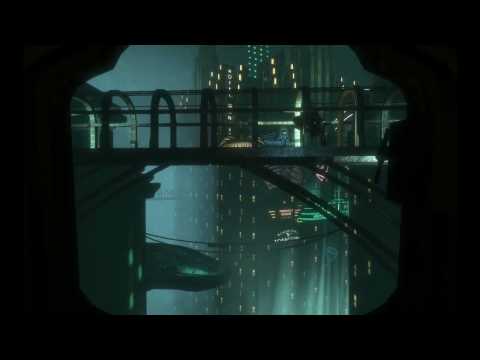

Streamlined doesn't always amount to dumbed down, though, and BioShock managed to take a pleasantly middlebrow approach to the shooter genre. Its tale was hardly a work of high literature, but it was nevertheless literate: Set amidst a collapsed undersea paradise, BioShock told a tale of Randian Objectivism. Personal freedom taken to its logical, apocalyptic extreme. In a place where "every man for himself" was a way of life, and science existed free of the mundane fetters of morality to curb its advances, the libertarian paradise that was Rapture had disintegrated beneath ambition, murder, and genetic experimentation run rampant.

"BioShock wasn't quite an RPG, and it wasn't quite an adventure game, but neither did it feel entirely like an FPS. It used shooting mechanics, the look and feel of '90s "Doom Clones," to accomplish something different than simply popping headshots — something more ambitious."

So yes, BioShock looked and played much like an FPS, but that wasn't really the point; the fact that its default setting imposed no penalties for failure made that much clear. Players were meant to explore Rapture, to face off against wandering supermen at their discretion, to follow vocal guidance from purported allies as they chose. BioShock often resembled a good Metroid game in the way it would point you in the right direction but leave the task of fine navigation up to you, forcing you to pay careful attention to your path.

As you worked your way through the interconnected chambers of Rapture, you tended to notice far more incidental details of the world around you than would have been the case in a more linear adventure frog-marching you from goal to goal. General details, like the masquerade masks (Rapture descended into chaos during a New Year's Eve party). Incidental story specifics, like the endless audio logs and posters for Dr. Steinman's plastic surgery lab. And, of course, the big picture: The destructive struggle between Rapture founder Andrew Ryan and mob boss Frank Fontaine.

No, BioShock may not have felt like much of an FPS compared to its more focused contemporaries, but it offered a degree of immersion those other games lacked. 2007 was the year that the FPS became frictionless; Halo 3 was extensively focus-tested and whittled down to a slick rollercoaster leading to its finale, and Modern Warfare took Halo's encounter-by-encounter design philosophy to its ultimate evolution, a pop-up shooter on rails. By contrast, BioShock was ugly, cumbersome, and rough... but therein lay much of its appeal. Its chunky play feel perfectly befit a world where art deco excess had given way to murder and decay; its sluggish pace turned its corridors into combat puzzles, allowing you no end of options for survival based on the powers you developed through experience and the dangerous (but potentially useful) tools you encountered along the way. And the extensive use of diegetic story audio lent gravity to your conflicts with the hulking Big Daddies and the mysterious, genetically enhanced Little Sisters they protected.

In a way, BioShock benefited from accidental genius. The player choice mechanic felt oddly lopsided — you could choose to harvest Little Sisters for their mystical ADAM or let them go free, but there was no downside to taking the moral high road. On the contrary, liberating the Little Sisters not only led to the best ending, it ultimately allowed you to grow more powerful than the "evil" route did thanks to the generous thank-you gifts the Little Sisters' "mother," Dr. Tennenbaum, would deliver periodically.

As it turns out, BioShock was never intended to feature choice; it was added at the insistence of the publisher. But the freedom to choose how to treat the Little Sisters perfectly fit the game's core themes of choice versus obedience, of selfishness versus compassion. Unwanted or not, it strengthened the central narrative, a perfect complement to the ultimate message of the adventure. The story's memorable twist, where (spoiler!) the player is forced through hypnotic programming to beat his own father — Andrew Ryan — to death with a golf club, serves as cutting commentary on the artifice of "freedom" in meticulously designed, story-driven games like BioShock. You can only choose the options the game allows, after all. But at the same time, Ryan's dying proclamation ("A man chooses, a slave decides!") also rings false in the hellish ruin of Rapture, a city where everyone was allowed absolute freedom of choice and all that resulted was disaster.

In BioShock, design and accident coincided harmoniously to create one of the most engrossing adventures in memory. It was lightning that seemingly can never be bottled; its sequels were good, but they fell short of the brilliance that made itself manifest here. Part shooter, part adventure, part sociopolitical tirade, BioShock absolutely stands among the greatest games of the century.