TGS: With Lode Runner Creator Doug Smith's Passing, The World has Lost a Gaming Pioneer

A tribute to the creator of the first Western-designed game to become a smash hit in Japan.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

While Jeremy is in Japan for Tokyo Game Show this week, he'll be blogging about interesting aspects of current Japanese game culture. Today, the passing of Doug Smith, who created one of the first Western games to become a major hit in Japan.

In 1986, my elementary school computer lab had finally begun to phase out its aging TI99-4/As in favor of more contemporary (not to mention more kid-friendly) Macintoshes. In hindsight, a room full of Macs was quite an investment for a school in those days, but we all took to the systems immediately and began expressing ourselves in all sorts of interesting ways.

I loved the Macs as much as anyone, but secretly, I only had eyes for a much older system, our school's sole remaining Mac forebear: The lab teacher's Apple IIe. Up until the Macs' arrival, the IIe had been the school's beefiest piece of hardware, easily shaming the countless TI machines the district had undoubtedly gotten on the cheap (Texas Instruments was a local manufacturer). It was enough of a beast that the lab teacher kept it around even after its mouse-driven successor had rendered it technically obsolete.

I didn't know about any of that, though. The Apple IIe played Lode Runner, and that was all that mattered.

It may seem strange in this day and age, when cheap and powerful computers appear not only in nearly every household but also in people's pockets (and soon on their wrists, it appears), but my family didn't have a computer when I was a kid. That didn't keep me from being drawn to and fascinated by video games, though; it just meant I had to get my thrills where I could. At the arcade. At friends' houses. And, after I ingratiated myself to the school's computer teacher, once a week in the lab.

Kids can be remarkably conniving and motivated when it comes to getting what they want, and I wanted to play Lode Runner, one of a handful of games installed on the Apple IIe that our teacher guarded ferociously; gaming on that system was a precious reward doled out for exceptional performance. So I volunteered for every opportunity to help in the lab. I leveraged my good grades and good behavior to finagle my way into a role as the official fifth grade lab helper. Every Friday, I'd spend some time helping clean things up and getting the computers back into order. (With Macs running System 2, that basically amounted to restarting the machines.) And when it was all over, I was allowed to spend some extra time in the lab doing as I wished. What I wished, of course, was to play Lode Runner. So while my classmates were back in the classroom working away at geography or something, I was trying to plunder all of the Bungeling Empire's gold.

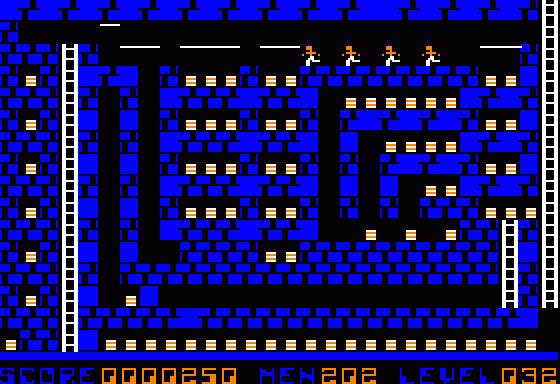

Lode Runner had a few things over other games of the era, but perhaps most importantly, it was fast. The game ran at an impressive clip, with fluid animation. Sure, the characters were rendered as simple stick-men, but I didn't mind; they moved with blinding speed and radiated far more personality than you might expect from such simple effigies of humanity. The minimalistic presentation of the game allowed not only for speedy action but also an impressive degree of intricacy in the level designs.

Lode Runner at heart was a maze-chase game, like Pac-Man. It didn't look or play quite like Pac-Man, but it grasped at the same fundamental appeal: You controlled a lone character beset by numerous foes. Unarmed, you could only evade your enemies and attack them indirectly — in this case by drilling holes that would cause your pursuers to become trapped and possibly destroyed once the curiously self-healing masonry of the stages repaired itself.

But trapping offered only a brief respite; a destroyed enemy would immediately regenerate elsewhere in the maze, sometimes appearing in the worst possible place. Taking the lethal approach was by no means a guaranteed solution. And your ability to create pits acted as a double-edge sword: Your lode runner (so called because his mission was to run around collecting piles of gold) could just as easily fall into the gaps you created... and unlike the Bungelings, you couldn't extricate yourself. You could easily become your own worst enemy

Lode Runner demanded the ability to look ahead and visualize routes, learn enemy patterns, and gain an instinct for the time your drilled holes would remain active and how quickly a Bungeling could free itself. Frankly, it was much more than my 10-year-old self could handle — but it was so well-designed, so fun, I felt compelled to try over and over again. Every week.

I didn't know at the time that Lode Runner was the brainchild of a single designer, Douglas E. Smith. At the time he invented the game, he had been a student not unlike myself, though a college student. I didn't know about the progenitors of Lode Runner, games like Heiankyo Alien and Space Panic. I also didn't know that Apple IIe was the original and optimal platform for the game; other systems tended to offer single-button controllers, but the IIe's joystick had two buttons, allowing me to drill blocks on either side of my protagonist.

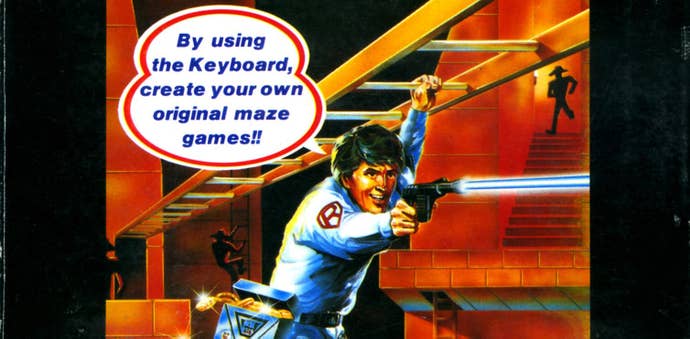

I also didn't appreciate what a magnificent innovation Lode Runner offered in its level editor. By many accounts, Smith's crowning achievement was the game's built-in feature that allowed players to construct their own puzzling stage layouts. Until then, game design had been a tool for the technically inclined; Lode Runner, on the other hand, provided a simple tile-by-tile interface that allowed players to cycle through stage attributes and make levels as intricate or complex as they liked.

In the early days, this became the Lode Runner legacy. Fans would send in their level designs, enough that the best of them soon found their way to a standalone release comprised entirely of fan creations. Critics and pundits alike applauded Lode Runner for being more than a video game; it was a tool for creativity and learning. No doubt this was how its presence was justified on our lab's Apple IIe.

In time, though, Lode Runner's legacy expanded well beyond anything Smith could have envisioned for it. The game sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the U.S., which in early '80s terms made it a massive smash success. But in Japan, it would sell millions. The game's 1983 debut and brisk action and simple-but-challenging mechanics made it a perfect fit for the new generation of game consoles appearing in Japan at the time. When Nintendo opened the doors to third-party Famicom licensing, Hudson's conversion of Lode Runner was first out the door. It became a monster smash.

Hudson's Lode Runner set the template for Japan's interpretations of the series: Cuter, chunkier. Hudson sacrificed speed for personality, but the essence of the game remained intact — and the Famicom's revolutionary two-button digital pad controller was perfectly suited for the game. Hudson even managed to retain Lode Runner's groundbreaking level editor, despite the lack of battery saves in 1984-vintage Famicom games. Instead, it could record to tape cassettes through a short-lived external data recorder peripheral.

Lode Runner's early presence on Famicom made it an iconic work for Japanese gamers — as beloved for those who were there at the beginning of Nintendo's long reign as something like Soul Calibur who were there for the end of Sega's. The game quickly found its way to a number of other systems, including multiple sequels for Famicom Disk System, Sega's SG-1000, and the Game Boy. Not all Lode Runners were created equal....

...yet the series retained a loyal following for years. Various Japanese developers continued dabbling with Lode Runner innovations well into the current century. Most notable among these was definitely Hudson's attempt to return to the well with Cubic Lode Runner for GameCube, an interesting if ill-advised effort to transform the game into a three-dimensional action title. In an interview with IGN more than 15 years ago, Smith somewhat bemusedly commented on Japan's eager adoption of his creation.

Despite hitting the big time with Lode Runner, Smith continued to work in video games through the end of the '90s with companies like DMA Designs (now Rockstar North) and Square USA (the defunct U.S. arm of the company now known as Square Enix). His credits include well-known titles like Lemmings, Final Fantasy VII, and Secret of Mana. Although his game credits dried up after the '90s — perhaps not coincidentally in the wake of Lode Runner 3D's failure to make a mark — his death, which current Lode Runner rights holder Tozai Games announced late last week, represents a true loss for video games.

Smith created one of the most innovative formative works of the medium, a game that managed to transcend international boundaries and become a beloved classic among American PC gamers and Japanese console fanatics alike. Level editors and game customization are taken as a given these days. And frankly, no one has ever managed to create a "trap 'em up" action game as fast, as diabolical, and as fun as Lode Runner.

I never personally met Smith, who dropped out of the games industry long before I entered the gaming press, but in some respects I owe him my career. Lode Runner captivated me as an elementary student, and the hoops I jumped through to play the game transformed it into something precious for me. It's no coincidence that one of the first games I bought with my own money once I finally managed to save up for an NES was Brøderbund's U.S. release of that famous Hudson port of Lode Runner. Smith's was a critical work both for a game-obsessed elementary student and for the medium as a whole, and today we're all poorer for his loss.