Ted Woolsey Remembers Final Fantasy 6, Evading Nintendo's Censorship Rules, and the Early Days of Localization

In 1994, a translator changed game localization by writing a "deathless" apocalypse.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

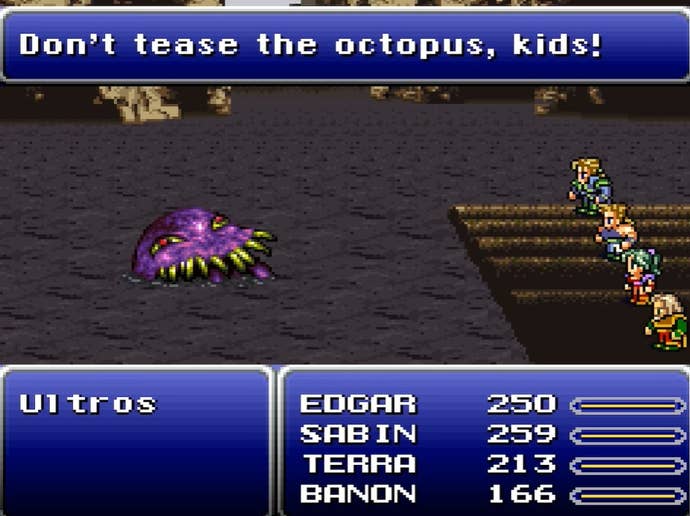

Every RPG enthusiast can recall what game they were playing when they were struck by the fandom's universal epiphany: The realization that RPGs can treat us to rich stories and deep character rosters that rival classic fantasy novels. We don't say it often enough, but the people who translated those games and added flavor to their characters, stories, and worlds deserve some credit for these discoveries. It's fine to journey for 60 hours with wooden heroes; it's better to come come away from the adventure bright-eyed and stuffed full of one-liners like, "Don't tease the octopus, kids!" and, "You sound like a chapter from a self-help booklet."

The 16-bit era was a renaissance for console RPGs, especially for Westerners. Though RPGs wouldn't reach anything close to mainstream popularity until Final Fantasy 7 hit the PlayStation in 1997, the candy-colored sprites in Secret of Mana and the solemn, realistic backdrops of Final Fantasy 6—released in the West as Final Fantasy 3— turned some heads and won some hearts. In time, these newly-baptized RPG fans and the veterans who fell in love with the genre through Dragon Warrior came to the same observation: Many of the RPGs produced by Square Enix (then Squaresoft) boasted next-level translations in an era where video game localizations were still infamous for being shoddy.

Squaresoft's RPGs weren't just clear and competent. They built up the worlds they belonged to, gave life and character to hero and monster alike. In particular, the localization for Final Fantasy 6 is so ingrained in fans' minds that certain character quirks and bits of dialogue have carried over into modern Final Fantasy games. Professional authors even cite Final Fantasy 6 as a major inspiration for their works.

It's remarkable to realize Square Enix's ability to deliver such a powerful story about death, devastation, and the end of the world while under the watchful eye of Nintendo of America's content censors. That's why the man behind the translations, Ted Woolsey, is still celebrated for his work.

There are slings and arrows too, however. The war between people who prefer colorful, highly localized interpretations of Japanese content and the people who prefer straight translations is as old as internet fandom. For the entirety of the 16-bit RPG renaissance and beyond, the liberties Woolsey took with Final Fantasy 6's translation was a hot battleground on Usenet, message boards, and IRC chat rooms.

No More Spoony Bards

Woolsey joined Squaresoft's American office at Redmond, Washington in 1991. Final Fantasy 4 had just been released in the U.S. as Final Fantasy 2. It was one of the biggest and most ambitious RPGs to exist on the SNES at the time. Its story took players across a vast overworld before it plunged down to an underground land, and then shot for the moon. Unfortunately, the epic atmosphere of Final Fantasy 4's journey was damaged when it came West thanks to a translation so poor, it still lives in infamy. Sure, Final Fantasy 4 gave us the wonderful, baffling scene of an agonized father crying "You spoony bard!" before launching himself at said bard for letting his daughter come to harm. But for the most part, Final Fantasy 4's SNES translation was full of broken sentences, grammatical errors galore, and strange glitches.

The translation wasn't just unpleasant to read, it was unpleasant to produce, which was why Woolsey was brought on to head localizations. Before Woolsey arrived, localizing games was a catch-as-catch-can task at Squaresoft, and several unusual "writers" contributed to the pot. "I think the process of finalizing the screen text had been so painful—even the finance lead and office admin worked to rewrite/edit the script until it passed certification at Nintendo of America—that Square actively searched for some options to improve things," Woolsey tells me over email.

When Woolsey began working with Squaresoft, he wasn't necessarily a fan of console RPGs. He played King's Quest and similar PC RPGs, but immediately noticed that works like Final Fantasy 4 "tasted like something fundamentally different." Humbled by the scope of Squaresoft's stories, he was determined to do them justice with his translations. His first job was Final Fantasy Legend 3 for the Game Boy (which is actually a SaGa game that was localized under the Final Fantasy banner for the sake of name recognition).

"It was surprisingly long script with tons of complexity for a Game Boy product, and I learned much from my mistakes," Woolsey says. "I think on that title I started to get deeper into the narrative voices, opportunities to play with humor—and how to spot scatological humor that wouldn't pass muster at Nintendo of America."

Nintendo Says "No, No, No"

You probably won't find many localizers today who boast the ability to competently re-write poop jokes on their resume, but it was a vital skill for anyone localizing games for '90s Nintendo of America. Before the implementation of the ESRB in late 1994, Nintendo of America was strict about keeping its games family friendly. It became especially fastidious when Mortal Kombat's over-the-top Fatalities caused the media and the United States government to wring its hands over violence and other inappropriate video game content.

Professional localizer Clyde Mandelin has a comprehensive list of content considered "verboten" by Nintendo's early '90s localization standards. Bloody violence on the level of Mortal Kombat was obviously out, but Nintendo's No-No List also forbade nudity/sexual acts, swearing, religious imagery or terminology (God, Satan, Buddha, Hell, etc.), and any depiction or use of drugs or booze.

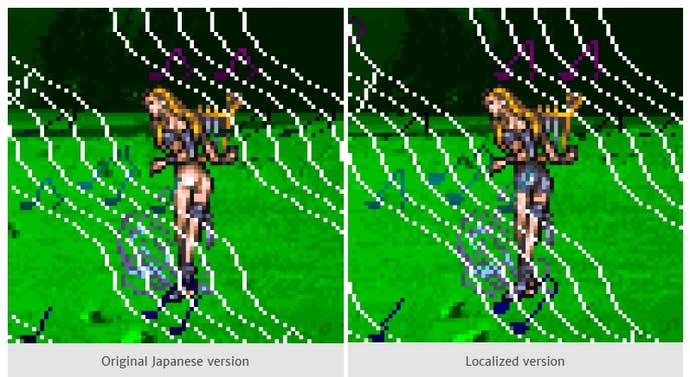

Squaresoft's 16-bit RPGs aren't necessarily bloody, but they contain plenty of mild swearing and the occasional bare bum. If you look at Mandelin's list of forbidden Nintendo content, you can see a specific example of how Final Fantasy 6 was altered when it came west: "Siren," an Esper who can be summoned by the good guys to put monsters to sleep, is airing her butt cheeks in the game's Japanese art. She was covered up for North America.

Final Fantasy 6 doesn't have flagrant nudity everywhere, but it is one of Square Enix's most mature works. Though the story starts with a typical narrative about a power-hungry Empire, everything spirals out of control and the world literally ends. Innumerable people die. Kefka, the insane god-clown ruling over the ruins of the world, only wishes to snuff out every life still scrabbling for sustenance in his broken kingdom. One by one, Final Fantasy 6's cast struggles to find its purpose in a seemingly hopeless universe.

Major parts of Final Fantasy 6's storyline involve suicide, teen pregnancy, and mass slaughter. Its length, depth, and gravity make it a difficult translation under the best conditions. But when Final Fantasy 6 was being localized, Nintendo disallowed words like "die" and "death." Ted Woolsey was expected to tell North Americans a story about the Apocalypse, and he had to do it without inferring that anyone actually dies.

We see poor little NPC character sprites get stabbed, choke on poison, fall into chasms, and even get squished between tectonic plates when a piece of earth heaves to life and launches skyward. But they're not dead. They're "doomed." They've "passed on." When your party falls in battle, they're "annihilated." It was OK for Final Fantasy 6's translation to suggest the party had been obliterated. What matters is they didn't "die."

I ask Woolsey a simple question about Final Fantasy 6's translation: How on earth did he manage?

Don't Say "Die." Say "Obliterated" or "Annihilated." Much Friendlier.

No surprise: Translating Final Fantasy 6 wasn't easy. Woolsey started the job by getting to know the characters, which inspired him to do right by them.

"I played as much of the game as I could to get a sense of the scope. I felt a connection to the characters and when I began translating—it felt as though I were channeling their personalities, enjoying their foibles and pitfalls as I proceeded," he says. "In the end, I grew to care about the games in a very personal way that made me want to try and keep producing better work, a credit to the creative teams at Square."

As he played, Woolsey was able to identify some of the narrative arcs that probably wouldn't get through Nintendo of America's content filter. He devised ways around them whenever possible. "I wanted to pull as much of the drama in as possible, to try and retain what I could of the more shocking events in the game," he says. "I did my best to try and find alternatives and work around some of those blockers."

Woolsey found some interesting ways to make Final Fantasy 6's startling moments more appropriate for western audiences, and it's interesting to look back on what Nintendo gave a pass. A subplot involving a pregnant 16-year-old and her terrified boyfriend could remain—as long Woolsey made the two a married couple. The conflicted heroine Celes was still allowed to attempt suicide when she hit rock bottom in the second half of the game—as long as Woolsey made it seem as if she jumped to "perk up."

Celes' jump doesn't make sense in the context of the game either, but suicide was obviously a firm "no" in Nintendo of America's books. Woolsey did what he could, which forced him to come up with creative solutions for several despair-ridden NPCs who likewise jumped to their deaths. Celes learns these NPCs actually "passed away from boredom and despair." This is another instance where the "softened" localization winds up being more disturbing than the source material. A quick end by suicide seems preferable to wasting away on a lonely island surrounded by poisoned water. It's like seeing your party "Annihilated" versus just being told "You have died."

On the plus side, these weird oversights by Nintendo arguably made some of Final Fantasy 6's most intense moments that much more memorable for western audiences. Whenever something naughty did slip through, it seared your brain. I distinctly remember visiting the town of South Figaro in the second half of the game and spotting a man and a woman hiding amongst some trees. When you talk to the couple, the man says something to the effect of making new lives to replace the ones lost. He runs off, and the woman follows. The NPCs aren't exactly undressed and fumbling at one another, but the implications are clear. I ask Woolsey how this interlude slipped under Nintendo's hawk-like gaze. He admits the jumbled process of translating old RPGs made it easy for things to slip between the cracks.

"That [scene] is a good example of one of the issues of localizing a huge game composed of multiple discontinuous files," he says. "I probably had no idea what the context was for that dialogue and since the game was so big, it is possible that NPC exchange never made it into the VHS tape(s) we had to make to accompany each submission to Nintendo of America.

"There were hundreds of short blurbs or asides like that in the text files which led to some anxiety. As well as translation gaffes."

In retrospect, I'm glad the scene remained. A big part of Final Fantasy 6's message involves fighting back against darkness and despair. The randy South Figaro gent's celebration of life isn't subtle, but his heart (or otherwise) is in the right place.

The Joys of Stuffing 50 Pounds of Text into a 10 Pound Bag

Despite its long list of localization "Thou Shalt Not's," Woolsey says Nintendo of America wasn't necessarily his biggest hindrance in translating Final Fantasy 6. (Though he was asked to revise and resubmit parts of his localization more than once.) Unfurling Final Fantasy 6's text from compact Japanese characters to the sprawling English alphabet required a lot of memory in a time when a 32-meg cartridge game was considered enormous—and had a price tag to match.

"The hardest part of that game was the sheer size of the text versus what the EPROM [erasable programmable read-only memory] could accommodate as far as memory," Woolsey says.

"At some point I just had to dump the side-by-side Japanese and English translation and keep flipping sentences around and shortening things until it finally fit into the ROM configuration."

Woolsey hated to chop the script, and he believes "the game was poorer because of it." Unfortunately, it was necessary. "Final Fantasy 6 was still one of the most expensive SNES titles shipped in North America due to the memory capacity required to house the game," he says. "That in itself was a barrier to entry for the game for mass market consumers."

Indeed, it wasn't unusual for RPGs to sell for close to $100 USD. Phantasy Star 4, the Sega Genesis' best RPG, retailed for more than $80 USD thanks to its hefty 24 megs of memory. There are several reasons why Final Fantasy 7 successfully booted RPGs into the mainstream, and its CD format is undoubtedly one. The looser memory restrictions eliminated the need to build bigger cartridges, which in turn dramatically lowered the price of RPGs.

Thankfully, Woolsey's work received a careful makeover with 2006's Final Fantasy 6 for the Game Boy Advance. It did an excellent job of "completing" Woolsey's translations while retaining its charm. The translation was headed by Tom Slattery, who talked to RPGamer about the process in a 2012 interview. Final Fantasy 6 Advance is hard to find, but Clyde Mandelin has a thorough breakdown that compares Woolsey's translation to the re-translation. Final Fantasy 6 on mobile and Steam also use the re-translation, though the game's "upscaled" sprites and backgrounds leave something to be desired.

When Mistakes Become Canon and Fans Get Furious

Woolsey's clever alterations to Final Fantasy 6's script and his dedication to the game's characters still echo in ways he never expected. As Woolsey himself admits, parts of Final Fantasy 6's translation are odd. Sentences often feel truncated, no doubt because of the strict memory limitations Woolsey worked with. Despite these problems, Woolsey's Final Fantasy 6 translation built up characters like no other RPG had at the time. His influence lingers: In Final Fantasy 14, players can fight a manifestation of Kefka, who cackles about making "a monument to non-existence"—a line Woolsey penned for the mad clown in 1994.

Even Woolsey's translation errors continue to influence the Final Fantasy series. Ultros, a giggling purple octopus with an irrepressible personality, was born in Final Fantasy 6. Ultros' name is supposed to be "Orthros," a reference to a two-headed dog monster from Greek mythology. But Woolsey gave Ultros a twisted sense of humor and ridiculous one-liners; even now the octopus usually keeps Woolsey's mistranslated name when he hops from game to game. The Final Fantasy 14 server named after him retains the "Ultros" moniker.

This Ultros slip is an example of a "Woolseyism," a TV Trope that references Woolsey's tendency to change RPG scripts (whether out of error, necessity, or narrative preference). Woolseyisms, which can extend to any Japanese-to-English media, are generally regarded as a positive thing. "Some of [Final Fantasy 6's] lines [are] so well integrated into the collective consciousness of the game that they have been embraced by the fandom instead of reviled," states the TV Tropes entry on Woolseyisms.

Woolsey is chuffed about his TV Tropes legacy. "Very cool, of course, to read through," he says. "Something like that makes you seem smarter than you are."

The TV Tropes page points out not everyone is a fan of Woolseyisms, and Woolsey acknowledges not everyone is a fan of his methods. "I've had my critics—gamers upset because I shortened or changed something, used a different name, etcetera," he says. "Sometimes I just outright blew it, of course! I understand and respect the passion and criticism—I think it is a function of localizing something that becomes iconic over time. It is difficult to explain to a broad audience why there isn't always a perfect or even reasonable one-one correlation between the original language and target language."

Not all of Woolsey's criticisms were deserved, however. RPG message boards in the late '90s and early aughts lit up with accusations of Woolsey censoring content in the games he translated when the case was Nintendo made the rules, not Woolsey. In fact, Woolsey did what he could to prevent Nintendo's rules from warping Final Fantasy 6's story and dialogue. Unfortunately, it was difficult for critics to grasp the complicated compromises that went into translating the game. It was easier to get angry and lob accusations across the internet. There is truly nothing new under the sun.

"Yeah, there were some very angry people. I understood the passion, and it would have been impossible to explain to everyone what the huge trade offs [with memory capacity] were," Woolsey says. "We had a platform, the SNES, that came with rules and regulations that were in place and needed to be followed if we wanted to ship. I had to be pragmatic about it all, but of course sometimes was taken aback at how vitriolic some of the attacks were."

It's not fun to stand directly in a stream of fan-venom, but Woolsey understands the fans' frustrations. "As I said, I think when people are deeply moved by these kinds of game experiences, they become defensive and inquisitive. I was one of the people between them and the 'authentic experience' they hungered for."

Woolsey currently works at the game studio Undead Labs as general manager, but he retains his love for localization. "I have never stopped missing it," he says. But localization has become a much more involved process since the '90s.

"Most games require studio work and script writing skills. Seems like for many larger games they need more of a Hollywood-style writing crew to handle the production work and real time edits demanded during recording," he says. "That's a world away from where I started, typing away in a quiet office."

Social media still argues—sometimes rages—about the superiority of pure translations over more liberal localizations, and vice-versa. The discourse is a mess; it's a tire fire that'll never burn out as long as there's always a controversy to throw on the blaze. Ted Woolsey didn't start the fire (with apologies to Billy Joel), but his RPG translations—and his translation of Final Fantasy 6 in particular—sparked the idea that game localizations can offer more than simple stories. They can offer something akin to epics, interactive novels that you never forget, even if the content within has been scrubbed to meet a vague standard of purity. Woolsey might not be in the industry spotlight like Hideo Kojima or Shigeru Miyamoto, but the mark he made on the JRPG genre during those days he spent "typing away in a quiet office" is indelible.