Taking Games Seriously

Eurogamer's Daniel Starkey explores the new academia that's growing around games.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

For decades, video games have strived for cultural relevance.

Cultural identity struggles instigated by spats with politicians or critics from other media have led to a complex among many gaming hobbyists as well as designers and developers in the gaming industry -- that this medium has serious potential and deserves the same level of respect and critical scrutiny as any other. At the same time, there's a rise of game development programs and degrees at universities across the world; professorships, residencies and long-form game criticism are helping games through their adolescence and into adulthood.

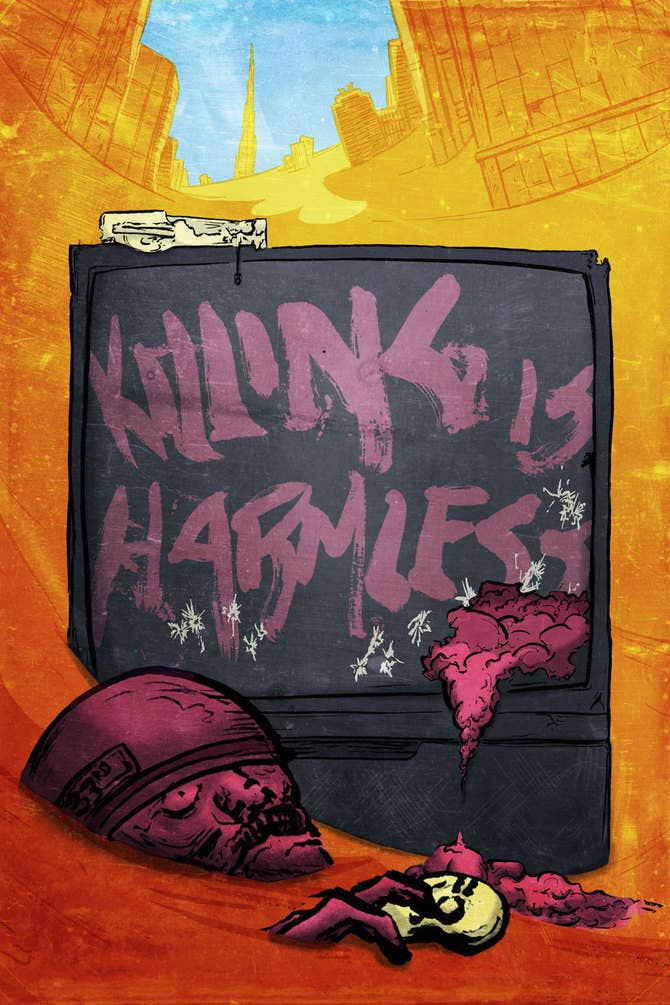

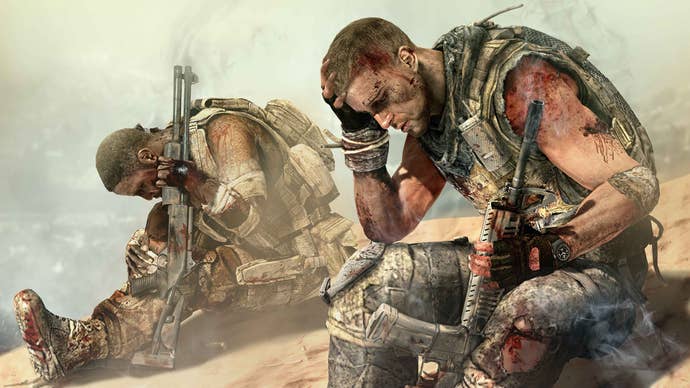

Killing is Harmless is perhaps one of the first attempts to boil down the essentials of a single game and provide focused long-form examination. Its subject, Spec Ops: The Line, darkly satirizes military shooters, games dominated by extreme death and destruction on positively ridiculous scales. The stakes are always tremendous and often involve terrorism, nuclear warfare and old Cold War tensions triggering new variants of last century's conflicts. Spec Ops: The Line takes heavy cues from classic, secondary school literature and approaches these games with skepticism. It doesn't say anything particularly unique, but it does so in a new way and specifically targets the demographic that mindlessly consumes the latest Halo or Call of Duty.

Brendan Keogh, the book's author, is a doctoral student from Australia. Along with his other project, Press Select, he's started something that he hopes will become the new norm for game criticism. "I used to go into book stores and go to the 'Culture' section and there would be books on a single film or books on a single music album. I used to always look for books on a single game because surely that existed, right?"

Except it didn't. Keogh wants to change that, move away from "objective" reviews that simply scroll through a checklist of must-haves; totally divorced from the culture that spawned them.

"I got super into the idea of critiquing popular culture while, at [school], I started to really enjoy writing", he said. "[I] pretty much tried to do 'What we do with films in class, but with games.' Not that I want games to be films, but that I think a single game is as worthy of critical attention to themes, aesthetics, and all that jazz no less so than a film. Or a novel or a theatre show or a dance or a poem." Now he occupies the ivory towers of academia, but wants to ensure discussions of games are accessible.

"I would like to see a broader appreciation in the industry of the fact they are not creating products but creative works, that they are producing and influencing culture with every game they release, whether they want to or not. I would like to see more game developers respect themselves as artists, essentially, even if they still try to be profitable."

Ian Bogost is perhaps one of the most influential figures guiding game design theory and working to shape the young art form. Noted as a professor, researcher and department chair at Georgia Institute of Technology, Bogost has written several books on criticism and design and frequently presents his findings and thoughts at professional conferences around the world.

Advocating the reconsideration of games' expressive potential, he writes on his personal blog, "Adolescence is videogame culture's greatest fear. That we will forever be stuck with juvenile power fantasies: fast cars, Big F**king Guns, and boob physics. That videogames will be lost to adulthood like comic books once were... Narrative writ large is mired in a permanent adolescence that videogames can now easily equal, the modest, subtle pleasures of the literary arts melting under Iron Man's turbines, impaled by Katniss Everdeen's arrow. Eventually adolescence ends, and we leave it. Unless it has fixed itself as our greatest aspiration."

Games, he says, have reached the critical level of saturation in pop culture necessary to move outside of the bounds of idle entertainment and into the realm of the serious, and affecting.

Brenda Romero, a game designer in residence at the University of California Santa Cruz, largely agrees with that potential. Notable for having a major part in the formation of both the tabletop gaming industry and the video game industry, Brenda is a veteran and literally wrote the book on Sex in Video Games. Since about 2008, she also worked on six board games collectively titled "The Mechanic is the Message". These games aim to tackle complex and emotionally charged topics and represent each of them through play. The New World, for example, wrestles with the harsh realities of the Middle Passage and the movement of captured slaves from Africa to the Americas. Train tasks players with rapidly and efficiently organizing pegs representing people into train cars. Only later is it revealed that the cars are destined for Auschwitz.

These types of games aim to communicate entire experiences. Instead of reading about slave ships or watching a movie about the persecution of Jews under the Third Reich, players live these moments of history. In so doing, these games can tap empathy more effectively than any other medium yet devised.

In a TedX talk, Brenda also described how she used The New World to teach her young daughter about the Middle Passage. The anecdote strikes a chord as Brenda describes her child's initial difficulty in understanding the real human cost of the slave trade. Instead, that same message was communicated effectively and ultimately internalized by a seven year old. Her participation in the facsimile of Triangular Trade made the entire concept real for her on a very personal level. Few media can claim to be so efficient at teaching such complex ideas - especially to young minds.

Echoing a similar sentiment, James Portnow said, "This is a medium like no other in the history of humanity, it's a medium where the audience isn't merely audient but participatory. The player has volition in a way that no 'viewer' does over their experience and this means that we can do things, we can explore human nature in ways we have never been able to before. This seemed like it deserved to be used for more than a way to kill the hours between work and sleep."

Portnow is a Master's Professor at DigiPen, a trade school that produced Narbacular Drop, the game that helped birth Portal. His students readily discuss his novel method of teaching. He focuses on the positive and asks that his students not just become great game designers, but collectors of life experiences. To craft a truly great game and communicate effectively through interactivity, he says," You first need to be fluent in life. Music, movies, books, relationships - everything."

When he's not teaching, Portnow is also one of the writers for the Penny Arcade TV show Extra Credits and recently launched a new, crowd funded project called Games for Good, which aims to change the popular dialogue about video games in the media. Both of these projects are meant to make the kind of academic discussions that might be shared at conferences accessible to the masses. They aim to democratize the medium in a sense, and in so doing help people develop a fluency in the medium.

More so than almost anyone else, James is almost ruthlessly optimistic. Despite the dozens of times games have been blamed for mass shootings, or for corrupting youth or being an intellectually vacuous waste of time, he still thinks it'll succeed as the next great medium of high art.

"I hope the industry continues to push the bounds of what can be done with interactive experiences. I hope that expense and familiarity doesn't frighten us into complacency." James said, "I hope that the next generation of players gets to play types of games I can't even dream of."

That, more than anything else, is a consistent thread tying all of these thinkers together. The desire, the will is there to do some something truly important with interactivity and to change the way we talk about games. They aren't made in a vacuum, they're products of the cultures that produce them and they have effects on the cultures that play them. Games are not only art, but they're powerful messages constantly being sent and received all over the world. With any luck a new wave of ludic-fluent professors, students and designers can take games to an exciting new realm of expression.