Steve Golson Interview: The Story of Ms. Pac-Man, the Atari 7800, and the Hyperdrive

The tale of how a group of MIT dropouts got sued by Atari, created the best-selling American arcade game of all time, and annoyed Steve Jobs with a fan.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

USG: What other games did you produce?

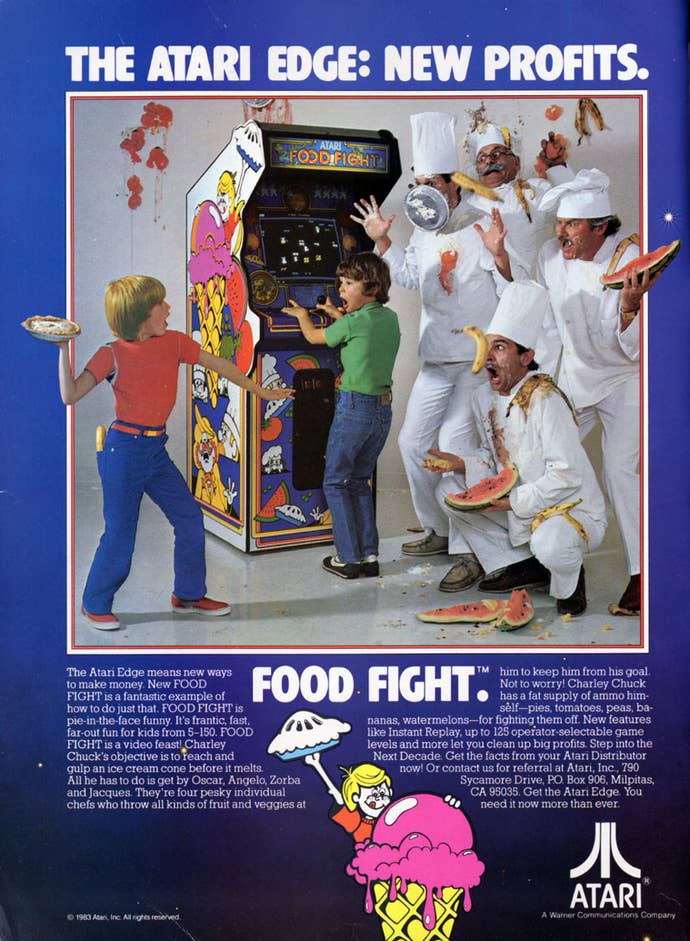

SG: Super Missile Attack, as a kit. Crazy Otto, which became Ms. Pac-Man and that sold 130,000 in the United States – the biggest build of any arcade game. For Atari, we designed two arcade games, Food Fight and Quantum. We also had a third game for Atari called Nightmare, which was complete and was out on test when Atari fell apart. That never got into production. However, it got far enough along where some Atari aficionados were literally able to fish it out of the garbage at Atari and get it working again. So there are some Nightmare games that you’re able to play – the guy that owns California Extreme has one.

For Midway, we did Jr. Pac-Man, and that came out in 1983. That was an obvious thing to do, so we did that as an arcade game for them. Then for Atari, we also did a tremendous amount of home cartridges for the 2600 and 5200, and the Atari 400/800 home computers. That really ramped up the work we were doing for Atari in '82 and '83.

We were very well known within Atari for doing arcade conversions. Atari would get the arcade title obviously for their own games, as well as other arcade manufacturers' games, like Dig Dug, Kangaroo, Xevious, and we'd put them on their home units. We did a phenomenal amount of that work for Atari in '82, '83 and '84. And then also in '83, we started work on what became known as the Atari 7800 Pro System, which was their next-generation home unit. The 2600 was very successful, but the 5200 wasn't. It had tremendous graphics, but wasn't backwards-compatible with the 2600. Technically it was wonderful, but there were so many flaws with it, it just wasn't very successful at all.

So we thought, let's do something that's 2600-compatible. We were in this interesting situation where actually, our development contract wasn't with Atari, but was with Warner. Some weird business reason why they wanted it that way. So we could go to Warner and say we wanted to develop this, and then hand it off to Atari and bypass all the horrible Atari politics and say here's a product for you to develop. Essentially, that happened. They had their own internal stuff going on at Atari, but we showed up with this idea and said, this is what we're going to do and it was obvious that it was a good idea. It had 2600 compatibility, and had amazing graphics for its day, and off we went. That was '83 and '84. We called it the 3600 initially, but it got renumbered once the marketing people got involved.

It was first announced in May of 1984, and Atari did this huge unveiling – here's our next-generation base unit for Christmas of '84. So think about it. If it's for Christmas, you've got to have it out in spring time so all the toy retailers can put in their orders, so it was going to be the huge big thing for Christmas of '84. We had 14 cartridges that we had designed, and a high score cartridge which was a really cool way of saving your high score from one day to the next, and there was going to be a computer keyboard peripheral, and it was going to be amazing. But then in July, Atari announced that they'd lost $600 million that year, and Warner sold it to Jack Trammel, and Jack came in and said we're a computer company, not a games company.

He was actually willing to put the 7800 into production, but at a vastly reduced dollar amount. The unit was supposed to sell for $150, and Jack said we're going to sell it for $80. And the cartridges, we were going to sell for $15, but Jack wanted to sell them for $8 each or something. There was only enough money in it for Jack, and nothing for us. We were like… "no"… and Jack was, "well, okay. We're not going to do games, we're going to do computers." So it sat on a shelf.

Eventually in 1986, Atari finally decided what the hell – let's sell the 7800, and it actually did quite well competing against the Nintendo NES – but it was two years late. It makes me wonder what the industry would have done if the 7800 had come out when it was planned, and what it would have done for Atari. I think so many in the industry didn't realize that a new generation of gamers was going to appear. The toy industry is so driven by fads, that in 1984 they thought the gaming fad was over, and they did not see it was going to come back – so kudos to Nintendo for bringing out the NES. But you look back and think, if only the 7800 had actually come out on time.

USG: What did you do after the Great Video Game Crash of '83?

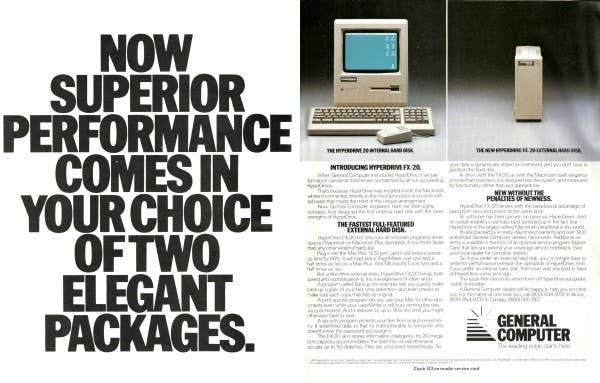

SG: We'd lost Atari, which was our manufacturing, sales, and marketing arm, and so if we were going to keep on doing games, we'd have to produce them ourselves. And frankly, the market had just gone through a terrible crash, so we thought, let's do something that'll make us money. At the time, we thought the Macintosh – which had only been out for a few months – was very cool, and we could see it was going to be a big hit. And just like our enhancement kits, you could see what this computer needed. And what it needed was a hard drive and more memory, yet it was designed to be a little beige box – the beige toaster – that you weren't allowed to get inside of. Well, there was a challenge for us! What could we do to the Macintosh, so let's figure that out.

So we figured out how to fit another circuit board inside this box that wasn't designed for it. Where can you fit a hard disk inside? So our guys made a paper mockup, and then we opened up a Macintosh and figured out that we could shock mount it inside the case. But then we realized there wasn't enough power, so we put in our own power supply. So that was the Hyperdrive, and it was the first really high performance hard drive for the Macintosh. So off we went doing Macintosh products.

There were a couple of things with Hyperdrive. Firstly, figuring out how to do it, which we did. Then we had to get control of the processor from a software standpoint. It turns out the original Macintosh had a self-test routine that was used for board testing, and the processor when it initially woke up looked out into this unused piece of address space and if it saw a particular pattern, it would think it was on the board tester, and it would transfer control out to the board tester and it could run. So that's what our code did. It pretended to be the board tester, and it immediately got control of the processor, and then it could run our ROMs and not the Apple ROMs. It was very much like hacking video games. It worked great – it was awesome.

We had an early negotiation with Apple because we didn't want end users to violate their Apple warranty if they had their brand new Macintosh ripped apart and the new board installed. This was done by a computer store. You'd buy an Apple Macintosh, and they'd also be a General Computer rep that would sell you the kit and install it for you without violating the Apple warranty. That was a critical negotiation.

Steve Jobs had been assured by his engineers that this was impossible to do: There was no way you could add a hard disk inside the Macintosh. Here's a story for you. I wasn't there, but the people who were took a Macintosh to Apple to demo it to Steve Jobs.

They bring in their Macintosh and they take it into Steve Jobs' office. First thing they notice is that there were no chairs. It's not that Steve's doing a power trip on you, it's just that he doesn’t think that anyone needs to sit down. The next thing is he comes breezing in, and says, "what's this?"

"Well, it's a Macintosh and it's got 48 more RAM chips on it, so it's got four times more RAM in it, and it's got a hard disk in it."

Steve was like, "Guys, guys. No. That'll never work. We work so hard to take as many chips out of it as possible, and you've added in all these new ones. It's never going to work."

We said, "It's working fine. It gives more memory."

Steve said, "There's not enough power. There's not enough power to run all that stuff. You're going to destroy the power supply."

We said, "Well, Steve, see, we put in our own power supply and grabbed right onto the 110, and we generate our own power. So there's adequate power."

Steve said, "Oh… well. But it's going to overheat. It's got all that stuff in there, and it's going to overheat. We carefully designed it so that there was just enough ventilation and it's going to overheat."

"But Steve, we put in a fan…"

"A FAN!?!"

So Steve Jobs was apparently totally against fans. He didn't like the noise, and he said, "This is terrible. You can't put a fan in there. It's going to be so noisy, people aren't going to like it."

"But Steve, it's running right now and you didn't notice."

"Oh.. well. It's the noise from the hallway. I'm sure I would notice it."

"Okay, thanks, bye."

But yet we negotiated with Apple to not violate the warranty, and so off we went with Hyperdrive, and it was a big success.

Since then, General Computer Corporation has transitioned into manufacturing and selling laser printers, which the company still does today. It's a far cry from its early days of modding coin-ops, but forms a fascinating story of how a company can evolve and change over the years.

Steve Golson currently works as a consultant under the auspices of Trilobyte Systems, where he applies his expertise in VLSI design, computer architecture and memory systems, and digital hardware design.