Starfield review: Shoots for the moon and lands with some qualms

Starfield’s grandiose scope sets the scene for a few under-developed ideas in an otherwise thoughtful, muddy take on the sci-fi genre.

Starfield is about humanity peeling back the mysteries of the universe to understand its place in the cosmos. Except when it’s about exploration. Or pirates. It has an anti-war message, sometimes, when it isn’t promoting the military. Sometimes there’s smuggling, but you can be a space cop, or a space cop who smuggles contraband and beats up debt defaulters. No one in Starfield really cares what you do most of the time, though some of your companions get a bit unhappy if you murder people.

I don’t really know what to make of Starfield. After roughly 90 hours and nearly two weeks, I have no idea what it wants me to think, do, or feel about any of its themes. Bethesda’s head of publishing, Pete Hines, said Starfield only really gets going after 130 hours.

There’s a lot going on, too much for Starfield to fully develop or explore (which is ironic, given the game’s core conceit). As a coherent set of ideas and goals, well, it just isn’t. But the fun to be had when Starfield isn’t bent on being infuriating is tangible. Compelling. Intricate. I even stumbled on some interesting and surprisingly thoughtful narrative themes, eventually. They're just tucked deep in the pockets of the galaxy, far beyond what's apparent to the naked eye in the beginning.

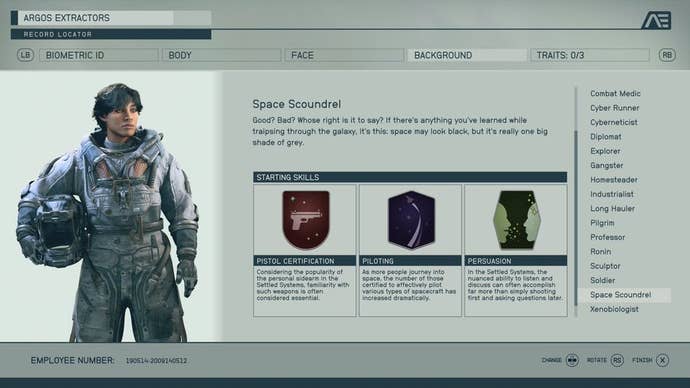

You start life in Starfield as a miner who stumbles on a mysterious artifact and has an even more mysterious reaction after touching it. Pirates invade; a man named Barrett theoretically swoops in to save the day (though you do all the fighting); and you end up with his ship and an invitation to Constellation – a storied band of explorers dedicated to surveying the galaxy.

As a Bethesda opening, it isn’t very good. The first step-out moment is rushed and uninspiring, and there’s nothing to anchor you in Starfield’s world, anyone in it, or even yourself. Your character is easily the studio’s least interesting protagonist, though that’s due in part to a lack of personality in most of your dialogue choices for roughly three quarters of the game.

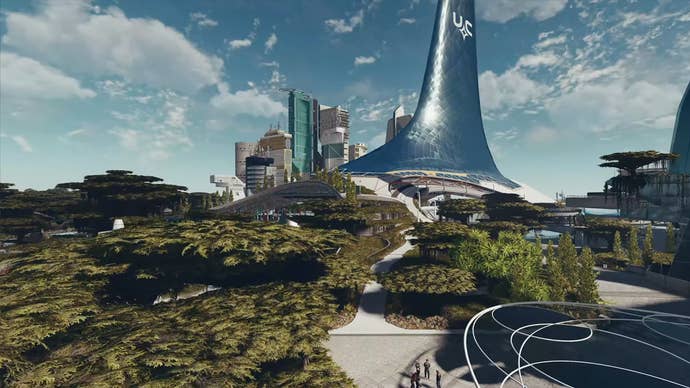

So off you go to New Atlantis, the oldest colony in the settled systems, a city with big theme park vibes and about six or eight character models that get reused ad nauseum for the nameless, unimportant people milling about. The other big cities are much the same – settlements themed around a few on-the-nose cultural elements, what you’d get if Disney made Epcot. In space.

Your next stop is Constellation headquarters, a cozy lodge that’s part-Victorian social club and part-high tech research lab. The Constellation missions move the plot along, your main story quests, comprised of MacGuffin hunts that ferry you around star systems and teach you the basics. You can (and should) also take on faction missions that plunge you into the Settled Systems’ murky politics, where the galaxies really come to life, and you meet a fascinating cast of characters.

A lot of the people you meet are broken and lonely, rootless, metaphorically floating in space with no direction. If not that, they’re working under exploitative conditions – or they’re the ones doing the exploiting. It’s a setup rife for exploration and some profound insights, but Starfield never quite asks why people are like this. It rarely investigates the human condition further. That lack of willingness to explore its own themes throughout the game is at odds with how rapt you can be in the intricacies of its world, of its systems. Starfield leaves you to do the exploring, thematically as well as mechanically, and how appealing that is will depend on the player. When it works, it works wonders.

Starfield takes American ideas and social systems and spreads them across the galaxies, which, okay, I have to admit that’s probably what us Americans would try to do if we lived in space. But the point is that it just doesn’t make sense for that to be all there is. All citizens of Earth left the planet and spread throughout star systems, so we should see more evidence of multiple cultures, societal problems and opportunities, and ways of thinking.

Instead, the overarching issues are essentially the same debates that occupied high-level American political thinking since the end of World War II – namely, the role of government. Starfield wants to make a statement about Big Government and bureaucracy in the United Colonies (and also problems with Big Military, though Starfield doesn’t like to bring that up too often). Then the Freestar Collective illustrates the potential hazards of the opposite, of loose, decentralized federations with little oversight. A tension exists between the statements the game tries to make, and though the minutiae is finely-detailed and well-textured, the overall package is toothless and inert.

One of my least favorite sets of quests was on Mars, where the only difference you can make for the oppressed miners there is helping them find ways to work harder, and more often, without changing the structures that exploit them. Extrapolate from that what you will.

Religion plays a significant role in Starfield, but the only religious and philosophical strains of thinking are rooted deeply in American and Western European traditions. Except the people who worship the giant snake god, branded as “foreigners”, who dedicate themselves to a holy war on behalf of their true god, because of course they do.

The limited scope for other ideas, other possible ways of living and thinking, holds Starfield back from being as deep as it probably wants to be. But, within those limitations, there are several deeper moments that stand out thanks to their attention to detail and thoughtfulness. And they make all the difference.

The Sanctum Universum is one of my favorites. The Sanctum is Generic Space Monotheism, but there’s a fair bit of nuance in how Bethesda created it. The priest on New Atlantis’ name is Father Aquilas (likely a reference to the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas mixed with a nod to Aquila from the Christian New Testament). The Aquinas vibes intensify if you read the church’s doctrine, which Father Aquilas wrote, where he combines strains of Plato’s philosophy with science and some forward-thinking monotheistic ideas about finding a god in space, blending several traditions into something new. Thomas Aquinas was famous for being one of the first medieval thinkers to do the same for Christian philosophy.

It’s a nice, even impressive, touch. And it’s when you see these delicate, artisinal flourishes in the galaxy that Starfield shows what it is truly capable of. Another example is a companion who arrived at a form of Deism – the belief that a higher power exists, but doesn’t meddle in human affairs – by reading Renaissance and Enlightenment-era philosophy. Those same writings inspired the first Deists in Western Europe, and there’s a welcome element of realism in having people recycle old ideas to come up with something sort of new-ish – that’s just what we do, and Starfield is at its most honest, and most appealing, when it realises these ideas wholesale.

“But… what about everything else?” you’re probably asking. I asked myself the same question after about 30 hours of traveling around, talking to people, and doing various odd jobs around the star systems, so I decided to find out. The answer is that it depends on what you’re doing and how invested you are in the idea of it. Starfield falls over itself to give you everything and let you be anything – though it rarely stops to consider whether any of it is worth doing or being.

In place of character stats and proficiencies, you get several basic skill trees, improving things like pistol firepower or your stamina. These are deceptively shallow, and the more points you pump into the many, many available skills, the more fine-tuned your character will be. None are essential, but they're all useful; isn't that a reflection on what it's like being alive now, a worker in today's gig economy?

You can mod your weapons – think Call of Duty gunsmith, not Cyberpunk sci-fi pipe dream. Mods, and other upgrades, require materials, and materials mean trips into the wilds of space to gather vegetables, animals, or minerals. You get as much out of these systems as you put in; it feels like they're here for role-playing, not essential to the gameplay loop. At least you get incremental amounts of XP for literally everything you do; even the most uninspiring trip into another barren planet yields something, at least.

.jpg?width=690&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp)

The space experience takes place mostly in an instanced space just outside a planet’s atmosphere, and it's bland. Nearby planets and stations are too far away for you to reach via normal travel, and getting around requires navigating several menus and loading screens – enter the ship, leave your location, travel to another, dock, landing, and leave your ship. At least it loads quickly.

But when you're in your ship, you get to dogfight. Starfield is so very nearly a deep ship-captain simulator, but a lot of the piloting systems are pretty illusions. Every dogfight has a kernel of excitement, though, even if you can see behind the curtain as you toggle systems on and off for the 14th time.

Starfield’s outpost-building trumps its ship management, and dovetails nicely with exploration. You can (and should) build outposts on planets to help with supply lines and resource management. It sounds sterile, but a generous selection of furnishings enables you to turn functional buildings into oases of style and comfort in the middle of the empty sea of stars.

Outposts are also a handy excuse to pick up new crew members to keep them running. These members vary between procedurally generated stock crew (such as a random gunner or navigator) to complex characters with deep and interesting backgrounds – some of whom ended up being my favorite characters in the game, despite them playing a comparatively small role. When Bethesda deigns to look at the dirt under its characters' nails like this, the developer is best in class. It's just in space, that's so few and far between.

Building outposts also costs money and materials, which pushes you to seek out more quests and hunt down some of Starfield’s hundreds of lifeless resource-rich planets. The loop is well-greased, and propels you on, eternally. Despite how beautiful many of Starfield’s planets are, most of them – even the ones with life – have just a scant handful of “points of interest”; caves, landing pads, random geological formations.

It’s possible that I just missed a trigger to make something happen at a few of these. Overheard conversations and being in the right place at the right time often causes something new and unexpected to happen. Who knows? Maybe if I stood in a ditch on a planet in the Narion system at sunset, something worthwhile might have happened at that empty industrial outpost on Titan. But with a game this size, that level of specificity risks being whispered into the ether, the consequences lost in the vastness of space.

.jpg?width=690&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp)

There are a lot of very good quests in Starfield, even outside the faction missions. This is where Bethesda’s “everything and the kitchen sink” approach works well. One mission has you tracking down hackers who tapped the cash resources in New Atlantis’ premier bank. Another borrows from horror games and sees you fleeing a terrifying monster as you try to find a way of defeating it, and a few minutes later, you might find yourself exposing political corruption at the highest level.

Some of these are just your basic fetch quests, but the context around what you’re doing elevates them and keeps things interesting. The downside is that most of the satisfaction is limited to how invested you are in that quest, since even some of the best missions have little lasting effect on the world around you. Maybe that’s a comment on real life, though.

Starfield is not greater than the sum of its parts. If you add all its misshapen, under-developed pieces together, you get kind of a ramshackle kitbash, with a few extra bits left over. Some of those pieces are cleverly crafted and engaging, representing a developer at the peak of its power, though they often get lost in Starfield’s sprawling scope. What remains is often enjoyable, but often frustrating. There’s no denying this cosmic behemoth is special, but with a more focused vision, and some extra narrative daring, Starfield could’ve been something truly incredible.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)