Sid Meier's Cultural Victory

"If there's anything in reality that's not fun, we'll change it."

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

There is an invisible line running through the middle of the 20th century - it makes landfall somewhere towards the mid-1950s, I think - and it separates two generations of American (and Canadian) teenagers. On one side - the older side - are the teens who think everything is neat. Neat rollerskates! Neat baseball mitt! Wow, that's a neat subscription to Popular Mechanics you've got going on there! On the other side are the cool kids.

Sid Meier, it turns out, is one of these - if only just. Ask him about his early platformer, Floyd of the Jungle, and he'll laugh accommodatingly and admit it was a cool time to get into games. Ask why he stopped making simulations, and he'll shrug accommodatingly and tell you he put all of his really cool ideas into the last one he worked on. The basic challenge of a designer is about being cool, too: "It's about finding what's cool and making sure it stays in and finding what isn't, and making sure that gets left out." Sid Meier, accommodating to the end, makes it all seem to simple. Making things seem simple - much like making things seem cool - is kind of his gig. In truth, though, it isn't really simple at all, is it? What's he been up to all these years?

If you've ever played a Sid Meier game - even one of the many which have had their own particular lead designers while still carrying his name on the box - you'll know what to expect. Simple inputs leading to wonderfully non-simple outputs, all the fun of real complexity channeled through a series of deceptively straightforward exchanges. Meier's best known for strategy games, and his reputation, in part, rests on the fact that he's managed to make them approachable without sacrificing their glorious depths. He's guided millions of players from their first settlement and on to the apocalyptic clashes of full-blown empires by way of that famous series of interesting choices he often talks about.

Meier argues that interesting choices lie at the heart of games. It could sound like empty philosophizing (like most maxims, it's been debated endlessly too), and yet, when you play his stuff, there's always that helpful structure waiting for you. Where to settle? When to build? What to research next? Congratulations - you've just hit the Renaissance.

The man, it transpires, is quite a lot like the games. In conversation, Meier's wide-ranging but level-headed, genial but precise. There's a peculiar kind of clarity to the thinking of this undemonstrative character with the grey zip-up cardigan, the dimly amused manner and the Don Rickles voice, blessed with an occasional Looney Tunes lisp - the same clarity that has helped shape the last few decades of games.

It's a clarity sharpened, perhaps, by the limitations of the first wave of home computers. "In the early days, we could never create a world on the screen that was as vivid as what you can create in your imagination," Meier explains to me when we sit down together in a Firaxis meeting room lined with framed game art and game disks - a lengthy career neatly arranged under glass. "The thing on the screen was just a stimulus for your imagination, basically. Now today we can get closer to showing you things that looks realistic, but your imagination is still more capable of creating something exciting than what we can put on the screen. We still look at the game as a stimulus for what we can get to happen in your mind."

He shifts the thought around in his head and nods to himself. "That's part of the reason why turn-based games work in so many cases, I guess: you feel like you have the freedom to take whatever time you want to think about consequences and possibilities. Your mind is doing all this cool stuff, and that's what we're trying to get to happen. We still remember that it's important to get the player's total brain engaged and not just the tips of their fingers."

This is a simple idea expressed in fairly undramatic terms, but it gets closer to nailing the richness of strategy games - the way that they can feel, at times, like the richest of all games - than anything else I've heard recently. It certainly nails the experience of playing Civ, at any rate.

Oh, Civilization! Sid Meier's most famous creation is a series that, as the name deftly suggests, puts all of human history at your command. It's a procedural reconfiguring of our species' entire experience in which the fate of nations plays out in a million different ways - although, granted, most of them conclude with Gandhi firing nukes. Civ's a game of real scope, in other words. It's a game that should be absolutely overwhelming - but in practice it rarely is.

"The core of Civ is the idea that the individual pieces, if you look at them in isolation, are actually pretty simple," explains Meier. "If you look at the rule about how your city grows or how combat happens, they're very simple and understandable. There's no mystery about how many hexes or squares this unit can move or how long it will take to discover a technology.

"So the complexity really comes in your mind as you trade-off or compare or evaluate different strategies," he continues. "It's not that you're trying to figure out what the computer's going to do or what random numbers it's going to roll. It's more like: here are all these pieces. It's like playing chess. Every piece is very well defined, but it gets interesting once they start to interact with each other. With Civ, you step in there and you kind of know the lay of the land - but what you do with all that stuff is where it gets engaging."

Civ's been engaging - and sometimes infuriating - its players for years, back since the first game was initially conceived as a real-time, rather than turn-based, offering. That aborted real-time version's interesting not just as an amusing historical quirk, though, but because it's a chance to glimpse Meier with his game design head on, sifting through rules and their consequences, zeroing in on nuances that the player may never notice, but which could still shape their experience nonetheless. When Firaxis designer Jake Solomon was working on XCOM: Enemy Unknown, Meier cautioned him that the project was leaning towards becoming a game that the player was always trying not to lose rather than one that they were striving to win, and, back in the early 1990s, he made a similarly quiet, similarly crucial distinction between different approaches to Civ.

"The original design of Civ was a lot closer to SimCity," he explains. "You'd just take SimCity and ratchet up the scale. I want to zone a city in this area; we're going to do agriculture over here. You'd stand back and watch the numbers move. Fun. It really distanced you from the game, though, and at one point we just said: let's try moving the units around and being very clear that everything happened because you did it.

"That was the a-ha! moment," he laughs. "Before that you were just spending most of your time watching the action. The really big thing was that your mind wasn't in the future wondering about what was going to happen next. Your mind was trying to unravel what just happened a minute ago. If you're behind the game, that's actually not fun at all. You want to be looking forward and anticipating what comes next."

That's the ideal Civ player as designer right there: staring down at the game from high above the action, yet able to put themselves on the ground in the middle of things when a problem appears: I'm looking backwards too much. I'm missing the real potential. Meier describes Civ as the project he's learned the most from, and that may be due to its wealth of problems - some of which have been easy to fix, others of which are seemingly intractable and have inspired the kind of creative thinking that intractable problems often do.

"With Civ 1, we were just amazed that it could happen," laughs Meier. "That you could pretend that the entire history of civilization was happening there on your computer. But it's natural for gamers to be unsatisfied - to have in their mind how I would have designed this game. Every gamer is a game designer. You play the game, you have fun with it, you see what's new and cool about it, but then you say, well, this doesn't work quite as well as I would like, or I would have changed this, or whatever.

"In the early days, we could never create a world on the screen that was as vivid as what you can create in your imagination."

"Take the endgame. There's a moment in Civ where you're like, 'I know I'm going to win, but it's going to be another 1000 years before that happens.' We've had lots of different approaches to tackle that - and the richness of Civ probably lends itself to numerous discussions of that type. There are these classic problems that Civ creates that we're always trying to solve: the endgame, combat. Still, we have the luxury of doing a new one every now and then so we can try and take some of these things and see what we can do with them."

Whatever you think of the various lead designers' solutions to the series' problems, Civ's longevity is fascinating, as is the passionate debates that erupt when a new version introduces extra victory conditions, or opts for hexes and removes stacking. The game is over 20 years old: why do people still care so much?

The answer may hinge on a couple of typically Meieresque distinctions, the first concerning the sly difference between learning and education. "We make a really strong separation between those two," says Meier. "Education is somebody else telling you what to think. Learning is you expanding your mind on your own or trying things out. Grasping a concept not because it was told to you but because you experienced it. That's the kind of thing that we try to provide in a game like Civ. That's the most rewarding experience for a player: learning by doing, and then owning that concept because you did it, because you tried the alternatives and that was the best one."

Secondly, Civ games are built from history but they're never bound by it. At one point in our conversation, I ask Meier whether he thinks the problem with Civilization's choice of endgames can be tied to the problem with, well, civilization's choice of endgames. None of those are much fun, either.

"We actually reject that point of view," he chuckles, leaning forward in his chair. "If there's anything in reality that's not fun, we will change it. There's no hesitation about changing the world, our vision of the world, our interpretation of the world, to make the game more fun. We're not restricted by what really happened or what's real. If it comes down to a decision between what's realistic and what's fun, we're going to choose the fun path and then rationalise it based on some obscure historical incident where the 300 stood off the Persians or whatever. You can always find some historical precedent to rationalise a decision you made. If Civilization isn't fun enough then it's not because civilization isn't fun. It's because we made a bad decision."

Meier's so serious about the designer's divine right to change history that he's enshrined it in one of his famous ten rules of game design: do research after the game is done. His rules are worth reading, as it happens, both for an insight into the games Meier's been involved with and, I suspect, an insight into the man himself.

There are common themes throughout, most notably an emphasis on respecting the audience and on not showing off - make sure the player is having the fun, not the designer/computer; just because we can doesn't mean we should. It's possible to sense a gentle, rather Lutheran morality running through the list at times. Other entries, meanwhile, can only be the result of experience: double it or cut it by half is my favourite: when you're in the middle of things, big changes are more useful to a designer than small changes. I asked a friend who makes games about this one, and he admits he uses it all the time: "It gets you moving in the right direction super-quick," he said. "And it gets you moving when you're just stuck."

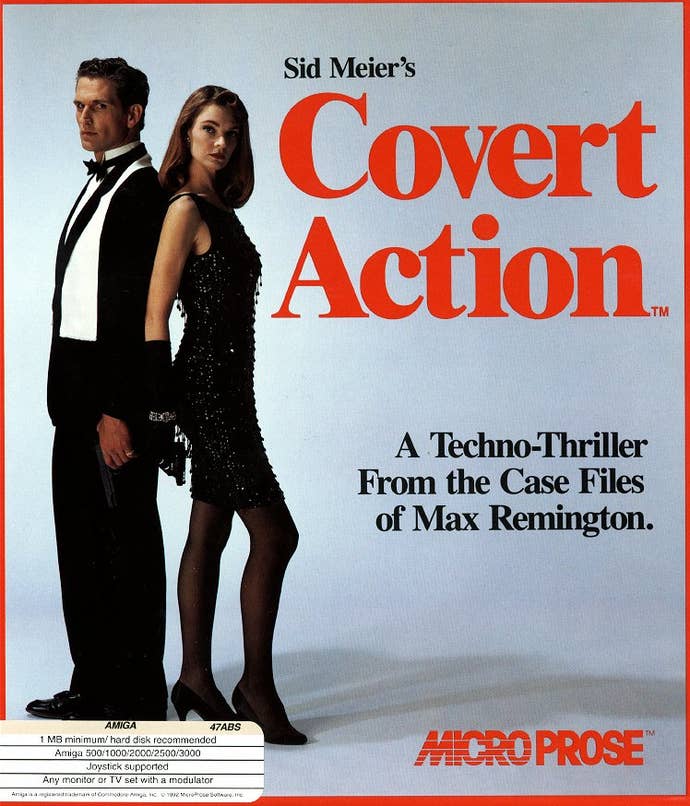

Civ remains a money spinner, but Meier hasn't limited himself to the narrow confines of, you know, human history. At MicroProse and now Firaxis, his name has been attached to spy games, simulators, even an oddball offering about Bach. "Back in the 1980s, we didn't have these genres to tell us what we could and could not do," he says. "That liberated us to do things like flight sims, Pirates! and railroad games. Floyd of the Jungle? No problem. It wasn't a case of finding a genre first and then picking a topic, it was picking a topic and then figuring out what are the tools, what are the gameplay elements that are going to make this work?

"I think we then went through the genre phase where everything was a real-time strategy, a first-person shooter, a turn-based strategy, and you had to define the genre first," he continues. "Today I think we're getting away from that again. Kind of because those genres are so full of stuff that we need to be innovative to get attention. It has to be... I'm not going to say weird, but it's tough! It's tough to get attention these days and one way of doing that is to do something weird. I think it spurs innovation in a lot of ways. Maybe nine out of 10 of these really innovative games don't work, but that 10th one pushes us and gives us new ideas."

Running a studio can be a bit like playing a strategy game, I suspect, and Meier's had to reroll the board at times. In 1996, along with the designers Jeff Briggs and Brian Reynolds, he left MicroProse, the company he had helped set up in the early '80s, to found Firaxis, where he works today. I wonder whether this decision was a real-world response to the endgame problem of 4X classics like Civ. MicroProse was a real beast by the mid-'90s - had it passed the exploration and expansion phases? Was Meier faced with a choice of exploitation and extermination?

"To some extent that's true," he says. "I have always enjoyed the design and programming part of what I do, and in order to do that it requires a publisher and a whole lot of people to let me do that. I've navigated my career based on: where can I keep doing those things that I like to do and work with good people to take care of the other parts? Every company has its own story, especially in this industry where there's such a lot of things going on. It's personally about me just finding a place where I can make games and work with good people, though. That was MicroProse for a long time. At a certain point things evolved and it felt like it could be better done in a different environment and that's where Firaxis came from.

"Part of our thinking was to go back to the good old days of a studio which was just focused on creating great games and was not as much involved in sales and marketing and all the other elements," he admits. "MicroProse was a public company at that time, and that brings with it its own pressures. It was time to remove some of the old distractions and get back to focusing on making games."

"If Civilization isn't fun enough then it's not because civilization isn't fun. It's because we made a bad decision."

Today, Firaxis' main series like Civ and XCOM may have their own design leads who operate with a lot of autonomy, but even a two day visit suggests a company that's been fundamentally shaped by Meier's personality. Based in what was once an old spice plant in Maryland - apparently it used to really stink of paprika - it's a friendly, rather studious place, broken into quiet groupings of little three- or four-man offices, each with a huge wooden factory door on rollers. In terms of deeper structure it's divided, albeit loosely, into developers who spend their time thinking about how to turn stuff like Anasazi pottery shards into an early game tech path, and developers who'd rather ponder how many shots a 1980s Corolla can take from a Sectoid before it erupts in flames.

For all Firaxis' dependency on storied series like Civ and XCOM, it's got one eye fixed on the future, too. Inevitable, right? That's how Meier wants people to play his games, after all. Perhaps, if you study history long enough, everything starts doubling back on itself anyway. "I really enjoyed those Floyd of the Jungle days," says Meier towards the end of our chat. "You kind of have to go with the flow in terms of where the technology is and where the audience is and what the hardware looks like. It's certainly been a trend with iOS and indie games and Steam and places like that where the smaller games are becoming a lot more viable in terms of getting published and getting recognition again, and people are being receptive to those kind of games. I love the game design part most of all, and in these smaller games you can do just as much game design as in a big triple-A game but you're getting it done in under a year as opposed to a couple of years."

Have there been constants in game design? Are there things that were true when Meier started making games and which are true now? "Actually, I think a lot more has remained the same than might appear," he says. "It feels like we're in an industry that, year to year, decides all of last year's rules are no longer valid and we have a whole new set of rules this year. In terms of game design, what works and what's core and what's essential when making a game, though, a lot of that to me really hasn't changed. That thing about how you really need to engage the player's entire brain and get their imagination working? That was a rule that was true when we started making games and is still a very useful thing today.

"Technology has shifted incredibly: multiplayer, the internet, forums, communicating with players. There are a lot of aspects that have changed, but those aren't really the central aspects. It's fun to see what the new platform is, what it can do, what it can't do, how we can apply our ideas to this new piece of technology. I still have a job because I'm a designer. If I was a programmer and I programmed using 1980s technology, I probably couldn't work today. If I was an artist and I could only do what I could in 1980 I probably wouldn't have a job today. I'm still designing with 1980s ideas and they still kind of work in the 21st century." He shrugs. "I picked the right career I guess."

Another constant, I'd suggest, is that Meier's teams continue to make games that refuse to be condescending to players. They break their complexity down into little pieces, but you still end up getting the full picture when you put it all together in your head, whether it's a tactical squad game that encourages you to juggle levelling characters with the specter of permadeath, or Haunted Hollow, a kid's title - on the surface - that leads you from learning the ropes to navigating base building and rock/paper/scissors combat in the space of about five minutes.

"The tone of our games?" muses Meier, "I guess that's just how I want to be spoken to, you know? It seemed a natural way to make games. They're called games, which can be a derogatory term, but they're a good thing! I'm often asked when I got interested in games, and I've always been interested in games. Everybody is interested in games. They're a natural part of being a human being. Treating the player as an intelligent person who's capable of making interesting decisions and understanding trade-offs, that's natural, too. Players enjoy learning and feeling progress and overcoming challenges. Yesterday they didn't do so well, today they're doing better. Tomorrow, they figure something new out. Those are the really rewarding moments."

Yesterday, today, tomorrow: he really does make it sound simple. It makes you think: we've all grown up with games, but not quite like this. Meier's been there for the entire story of video games, channeling us through complex ideas in a friendly manner. He's created some of games' signature franchises and he's found fascinating designers to take those franchises in new directions. He's helped shape games' cultural victory.

And that games have in turn managed to capture the mind of this creative, deep-thinking designer? That's probably a victory worth having.