Shear Terror: Nine Questions with Project Scissors' Hifumi Kono

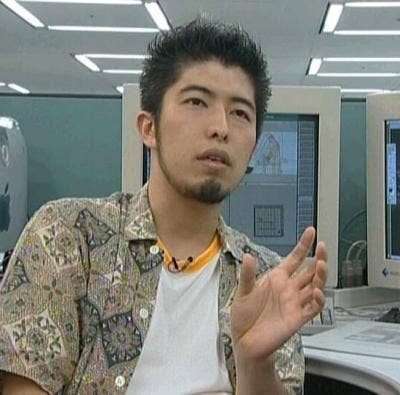

Clock Tower's creator shares his thoughts on revamping his classic horror series for a new generation.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

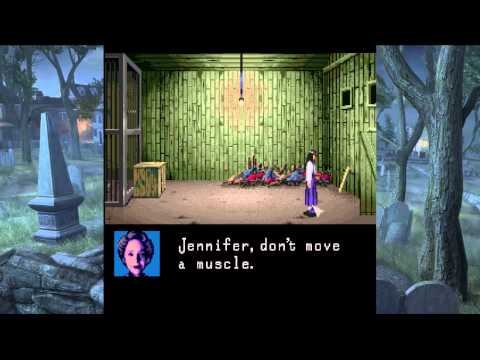

Though it doesn't carry the same degree of clout as Resident Evil or Silent Hill, Human Entertainment's Clock Tower series pioneered the survival horror genre in the mid '90s—and helped define the PlayStation as a platform full of experiences you wouldn't find anywhere else.

Nearly 20 years since the series' debut on the Super Famicom—and more than a decade since Clock Tower's 2002 PS2 swan song—creator Hifumi Kono is back with Project Scissors, a spiritual sequel to his original creation. Kono currently acts as CEO of the development studio, Nude Maker, and Scissors marks the first time he's touched survival horror since directing 1996's Clock Tower 2 (released for the PlayStation in America as Clock Tower). The gaming industry's been through an indescribable amount of changes since these much simpler times, so I caught up with Kono to see if his take on horror has changed in the passing decades.

USgamer: The Clock Tower games you worked on seem to be inspired by an older style of horror film—specifically, the work of Dario Argento. Have the many changes to the horror genre in the passing decades informed your approach to Project Scissors?

Hifumi Kono: I have kept my eye on how horror films have changed over the years. Peter Jackson basically killed the 80’s horror trend with Braindead (aka Dead Alive). After that, we witnessed the rise of situational horror with SAW and Cube. Recently, there have been good mockumentary and spiritual horror films, as well as innovative efforts with films such as Antichrist and Martyrs.

With these changes in horror, it took a while for me to formulate my “ideal” horror. Horror as a genre may seem limiting, but in fact it is a very deep genre, and I’m sure everyone has their own ideal horror. While I embrace and appreciate the diversity in the horror genre, I felt that as a creator, I should present my own version of ideal horror.

USg: Can you talk about what the consumer reaction to the original Clock Tower was like? Do you find, all these years later, people have accepted the idea of a video game experience where they're not necessarily empowered?

HK: [F]or Clock Tower 1 that came out on SNES, I recall it was only accepted by a limited audience due to it being different from the other games at the time. After Clock Tower, there has been an increase in games with limited methods of retaliating against the enemy, though not as extreme as Clock Tower. Thanks to such games, I feel the audience today feels less disinclined towards such game systems.

Plus, there is always the pioneer-type audience sensitive to innovation in every age, who are waiting for games with a new style.

USg: Did you feel that the relatively primitive technology of the Super Famicom and PlayStation held you back in any way? What can you do now that you couldn't before?

HK: I think the evolution with the camera-work and how much freedom developers are given is a big step forward. With the SNES and PS1, it was impossible to show the character hiding in a locker without situation-specific programming, and a unique set of graphic assets for that specific situation. Today, we can easily do this with the same graphic assets used in the game.

USg: The previous Clock Tower games played very much like the point-and-click adventure PC games that were popular at the time. Are you going for the same format with Project Scissors?

HK: For a common publisher, the point-and-click system is probably one of the first elements to be avoided. As we can tell from Capcom’s Clock Tower 3, it became almost common sense to get rid of the point-and-click interface when targeting a larger share of users.

However, the point-and-click system does have its merits, like allowing for a wider range of dramatic effect. And the horror I want to create is filled with dramatics. So, after looking at the game from all angles, I have decided to keep the point-and-click interface for Project Scissors.

USg: What do you think is the hardest thing about trying to scare a player?

HK: The atmosphere. From my perspective, I feel this is crucial to horror. Gimmicks that scare you, like a jack-in-the-box, or a sequence of gory scenes don’t make a good horror product.

Creating the atmosphere, and slowly breaking down the psychological barriers for horror for the monster to make its appearance. This is a classic and mainstream method in horror, but is most difficult to perfect. When done properly, I think it is the ideal method of creating horror.

USg: Do you still play adventure games? How do you feel about how they've evolved over the years?

HK: I play more adventure games than other genres. I was impressed with Heavy Rain, and voted for it as a member on the panel of judges, to receive the Game Designers Award for the Japan Games Awards. I was amazed at how adventure games had evolved, since we only see text-based adventure games with a limited budget in Japan, due to its limited market. There aren’t many high quality adventure games, but I hope the genre continues to survive as a genre we can really sit back and enjoy with a nice glass of whisky.

USg: Was it impossible to regain the rights to the Clock Tower name, or is this new "Project Scissors" title intended to indicate a new direction for the series?

HK: As unfortunate as it is, it is hard for creators with limited capital to hold rights for games. For all of the games that I have worked on, my main focus was investing in the development process, and not saving money, so I couldn’t buy the rights.

Another reason, and this is the bigger reason, is that the concept for this project is “a return to roots.” Clock Tower 3 changed the game system, which was supposed to be the ‘evolution’ of the Clock Tower franchise. In my opinion, however, the best game system for this franchise was the point-and-click, as implemented in the early Clock Tower titles.

At the same time, there are users that appreciate the game system in Clock Tower 3, and for users that started out with Clock Tower 3, I thought it unwise to revert back to the old system in the same franchise. So in order for me to create a game with an ideal game system, I needed to start anew and create a new IP.

USg: Can you talk about the biggest differences in game development between the mid-90s and today? Do you particularly miss anything about the older generations of hardware?

HK: The biggest change is in the expanded budget, and risks increasing with it. To risk-hedge, games began to be planned based on market research. This project is a resistance to the current situation in the industry. From a hardware and technological standpoint, I think it has become easier to create games today—with middleware such as Unity, graphic assets can be bought, and higher hardware capability allows for rich post-production. Since entertainment is tight-knit with technology, I think we have to look to the future, rather than just looking back nostalgically at hardware from the past. But to be completely honest, there are times when I miss the cheap-yet-image-evoking graphics of the past.

USg: What do you personally find scary? Have any of your fears made it into one of your games?

HK: Eraserhead by David Lynch is the scariest for me. Fear is an emotion that arises in the presence of the unknown, so I find inexplicable catch-22 situations most horrifying. Because trying to explain the situation adds to the horror by evoking further troubling imaginations.This is why when I create horror games, I don’t explain everything and try to stimulate the user’s imagination. I think this is clearly shown in the SNES version of the original Clock Tower.

A horror title that I had undervalued this past decade is The Beyond by Lucio Fulci. There seems to be an underlying meaning, yet the [film's] paradox rouses the imagination. But then again, there are many people who think Mr. Fulci is plain silly, but we may never know...