Sega's Time Machine: How Sonic Mania and More Signal a Return to Sega's Glory Days

As Sega seeks to revive old properties, they may as well revive an entire decade.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Sega introduced a new title card this summer. Their classic blue and white logo slides along a human eye, less of a reflection (because for one it isn’t backwards) and more like the eye itself is projecting the logo like a TV screen. It has a damp blue tone and a soft-center focus. It has a buzzy ‘buh’ chime that sounds like you just agreed to copy a file off a memory card. It looks like it listened to Born Slippy nine times in a row.

It looks like all it’s missing is a radical tagline, which Sega used to keep in a pile. "Welcome to the next level." "Sega does what Nintendon't." Someone just barking "SEGA!" It’s most reminiscent of the "It's thinking" campaign, focusing on themselves in relation to human parts. In a video titled "The Future of Sega," Yakuza creator and Sega’s chief creative officer Toshihiro Nagoshi waxes philosophic about the company. "When is a person moved?" he asks. "When their heart skips a beat?" He concludes that Sega looks for emotive bodily reactions to games, ergo the stricken eyeball. He explains that their new direction is "experiencing the unprecedented," though this all may slyly be a part of doing a bit of the opposite, to enable a moment when that was more possible.

The late-90s tone and rhetoric of this campaign and reports that Sega wants to revisit their catalogue are a rare opportunity for the unique company. It seems more than anything Sega wants to build a time machine and wants us all to climb aboard. Not merely reviving Sega’s greatest games, but reviving the aesthetics of the years we were excited to play them.

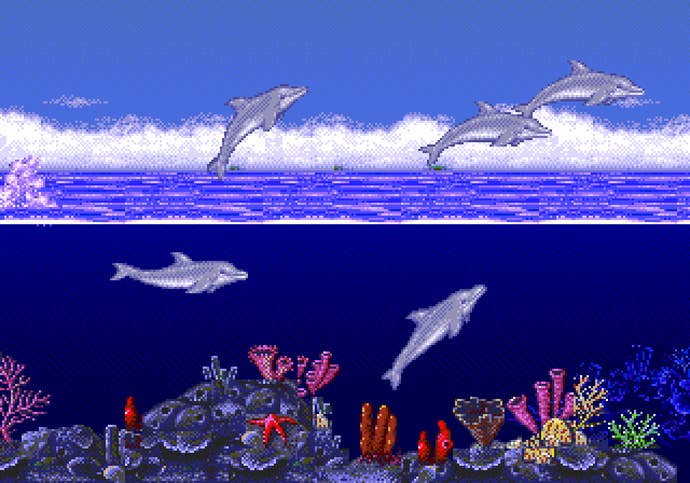

Sega has had a great strange history. In the late 80s they were relatively unheard of outside of arcades, but by the mid-90s had earned around 65 percent of the market share. They marketed aggressively. They opened up Japanese-style game centers around the world (some GameWorks, Playdiums and Sega Worlds are still hanging around). They introduced series after series, console after console. Sonic the Hedgehog. Ecco the Dolphin. Virtua Fighter. Sega Genesis. Sega Saturn. Sega CD. This jumble of hardware may have contributed to their downfall as competition tightened, but you couldn’t pray for a better closer than the Dreamcast.

Part of the reason Sega was so much more influential in the 90s than after is because they allowed themselves to become part of it. Nintendo and Mario are the Mickey Mouse to Sega’s Bugs Bunny. Mickey is timeless but also a little toothless, a Silly Putty personality that rises whatever the challenge is. Bugs is more irreverent, with attitude, co-starring in movies with Michael Jordan. That’s how you become part of a decade, how you become vogue—you try to become part of the culture. Heck, Sonic was almost a rabbit himself.

Sonic’s trademark is wagging his finger at the squares eating his dust, Mario’s trademark is saying his own name. Sonic’s early style guide has more shapes, static and layering than an 80s MTV ad fill. Sega gave grunge Comix Zone, hip-hop ToeJam & Earl, pop punk Crazy Taxi, and Electric Circus ravers Jet Set Radio. Sega was willing to anchor itself in a moment, but these plays dated themselves just as easily. Sega was more fashionable, and everything goes in and out of style.

After the Dreamcast dream ended, Sega became a publisher. They found some new hits with Super Monkey Ball, but it wasn’t long before they tried rehashing old properties. During the PlayStation 2 era they brought back Shinobi, Altered Beast and attempted a gritty Vectorman. But fans don’t just want retro things back by name alone. They want that warm nostalgic circa-98 feeling all over again.

Sega seems to realize that to stage a comeback, they’ll have to bring back their entire 'moment.'

There must be something in the air, because it's manifesting all over, and Sega may not even have to do most of the heavy lifting. There's Sonic the Hedgehog fashion collections. A vaporwave art leeching off Ecco the Dolphin that may or may not confuse its creator. A new Shenmue in the works. A new Seaman in the works. Very soon we'll have a new ToeJam & Earl to play with, largely based on the 1991 original. All three being made somewhat independently of Sega.

"Sega was really a groundbreaking company," says Toejam & Earl series creator Greg Johnson, who is releasing the newest game Back in the Groove with Adult Swim. The original T&E was an odd brew of roguelike and cartoon nonsense, a cult hit over the ages though its immediate sequel was a traditional platformer. Back in the Groove isn’t running from the past. It’s a slick, colorful high-def presentation of the original’s formula, two hip-hop aliens meandering around gathering space junk to escape Earth, a planet of idiots. In an email conversation Johnson says he loves the Sega catalogue, way beyond just the games he made for them. (Space Channel 5, Seaman, Alex Kidd and NiGHTS to name a few.) As far as Sega’s motion to revive the 90s, he thinks it’s the right move for the company.

"There is definitely a big retro-love movement in the games industry now," says Johnson. "I think it's great. Sega fans love those old games and that old feel. I think Sega is being smart." If this moment will help out the new ToeJam and Earl, he says we’ll just have to see when it comes out.

While there’s excitement for these revivals, nothing’s heated up the crowd quite like Sonic Mania, a game that doesn’t just look like it homages the 90s but looks like it was made in 1994. Sonic has always been Sega’s star, but their constant attempts to revolutionize him has worn down the speedy franchise. In the same way trying to become part of a culture glues you to it, trying to escape their roots has made Sonic look tacky and desperate to hop back into the zeitgeist. It seems those errors are finally being resolved, and the efforts may be rewarded. The creators behind Sonic Mania have their goals. "Our philosophy," says programmer Simon Thomley, "[is to] basically make the player feel what we did when we played back in the 90s."

Thomley’s family picked up a Master System from a Florida outlet store when he was a kid, but it was during a shopping trip in 1991 when he first met the blue needlemouse. "I saw the original Sonic the Hedgehog on display for the first time and was blown away by how fast and smooth it looked, how sophisticated the physics seemed to be," says Thomley. "As I watched it, I knew that not only did I want to play it, but I also had to learn to accomplish the same thing. I was 11 at the time. Within the year, my family got a Genesis, and from there I followed Sega through their entire hardware line and beyond."

Sonic Mania seems to be the ultimate tribute to 90s Sega. Not merely another 2D Sonic game, but one created as if it came out on the heels of Sonic CD for the Saturn. Those colors, motion graphics, sprite works, music, it’s all enthusiastic, magical, confident and bright. They seem untouched by the last two decades, unlocked from a time capsule. By placing the right fans in charge of Sonic, the game isn’t weighed down by any existential crisis for where Sonic can go ‘next.’ Thomley says the project is "a realization of a 26-year dream." Thomley and Christian Whitehead, who cut their teeth on fan-games before making official remastered versions of Sonic games, are working closely with Takashi Iizuka and Kazuyuki Hoshino of Sonic Team to ensure their tribute feels authentic.

Some of the newest elements seem completely unfazed by history. One of the new levels, Studiopolis Zone, is themed around cable television. It feels like it only makes sense in the context of the late-90s. The sunsetting cityscape feels like a backdrop for a bygone Late Show, and the various obstacles, gizmos and font-styles have a kind of peak-Turner Broadcasting worship to them. The idea was one Whitehead has had for a while, the name especially. The media-themed world also opened up opportunities for more Sega easter eggs.

"Everyone on our team became a fan of Sonic during his 2D era," says Thomley. "This is a game that we very much would want to play ourselves, and not only are there many older fans who are eager for the return of this look and feel, we also want to share it with newer generations. There are a few more colors and higher-fidelity music, but at its core, we tried to remain faithful to the originals in all aspects of the game's style. As such, we tend to look at the "target era" more in terms of “what if the classics had a 2D sequel on the Saturn?""

Sure, nostalgia is in itself trendy these days. Between games and film, audiences are becoming something of a test subject, poked with needles in the brain to see if a new Baywatch movie is more desirable than a King of the Hill revival. Netflix probably has an entire think tank around resurrecting Urkel. As retro overwhelmingly becomes the contemporary norm, to make an earnest connection with the audience is going to take much, much more sincere than some name recognition and sugar in the ears. It’s going to take a whole new sort of brand conditioning, not just reviving the property, but understanding the culture that propped it up. What good is a new X-Files season without the broadband conspiracy theory culture? What good is a new Sonic the Hedgehog without the confidence that Sega had with its inspiring bonafide ideas?

These cycles are nothing new, kingdoms rise and kingdoms fall and every young parent wants to take their kid to their first Star Wars. People like retro because people like returning to a special, whimsical place. The past is the ultimate escapism. Nostalgia is a lot like that goofy anomaly from Star Trek Generations, a floating uncontrollable ‘Nexus’ that will either teleport us back to a bygone Christmas morning or, I don’t know, destroy every planet in the star system. Being part of a moment may have frozen parts of Sega in history, but these days people want those moments back, not just the games but the feeling that the decade is continuing instead of being replayed.