Sega Genesis 25th Anniversary: The Rise and Fall of an All-Time Great

A retrospective and oral history of the life and times of Sega's most successful machine.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The Nintendo Famicom dominated the Japanese home market throughout the '80s. From the time of its launch in July 1983, the Famicom was the go-to system of choice for Japanese gamers for a decade -- and it performed every bit as well in America, where it launched as the Nintendo Entertainment System.

For years no one managed to make significant inroads into Nintendo's domination, but that changed on October 29, 1988, when Sega launched its Mega Drive console Japan. While Sega didn't manage to completely liberate Japan from Famicom mania, a little under a year later on August 14th 1989, the Mega Drive - rebadged as the Genesis - began an assault on the U.S. games market that would eventually crush Nintendo's command here. And in the UK, it finally convinced gamers to consider consoles as a viable alternative to microcomputers. The birth of the Genesis marked the beginning of a new generation of video games: Not just in terms of processing power, but the shape of the business as a whole.

Sega Genesis gave Sega its most glorious moment in the sun. And it all began 25 years ago.

The genesis of Mega Drive

Sega made its first bid for the console market -- seemingly by coincidence -- on the same day that the Famicom launched in 1983. However, Nintendo's system proved far and away to be more popular than Sega's SG-1000 thanks to its superior power, graphics, and software lineup.

But Sega didn't call it quits; despite their machine's relative lack of popularity, the SG-1000 still managed to perform far better than Sega had hoped, and they continued to produce new contenders to face off against the Famicom. The SG-1000 gained a computer add-on (the SG-2000) and a more powerful sibling (the Mark III); the latter even made its way west as the Sega Master System, where it made a tiny ripple in the U.S. and a much more profound impact in South America.

After a few years of trailing almost invisibly behind Nintendo’s lead, Sega stepped up their game by making an early entry into the next generation of consoles with a 16-bit monster of a machine. The Genesis was powered by the same Motorola 68000 chip at the heart of the Apple Macintosh (in fact, it ran at almost exactly the same clock speed as the original Mac), putting the system on par with a home computer. Despite the heritage of the Genesis' innards, though, the era of console-computer hybrids was well and truly over by 1988. Instead, Genesis used its power entirely for the purpose of playing video games.

"The Genesis has an odd duality in that it started as a competitor for the NES and continued to stay ahead of the SNES. The style of games being made for it changed drastically, from the simple to the more modern-feeling. I think Genesis is especially interesting to fans of Nintendo platforms. It's a shame that these days almost all you can find in thrift shops and secondhand stores are worthless EA sports games. The system gets a bad rap because of that, but it has a lot of great games worth seeking out."

Jeremy Hasse

Sega’s wasn’t the first home system to dabble in 16-bit processing by any means. Mattel’s Intellivision actually ran on a 16-bit chip, if you want to be technical, and NEC’s PC Engine (TurboGrafx-16) used a 16-bit graphics chip to add extra muscle to the 8-bit processor at its core. The Mega Drive, however, left those other machines in the dust. While its capabilities would inevitably be eclipsed by the Neo-Geo and Super NES, it got its foot in the next-generation door early at a time when people were starting to hunger for experiences beyond what the NES could offer.

Arcade at home

With the hardware design of the Genesis, you could argue that Sega beat Nintendo at its own game. Nintendo's strongest consoles have always been based on low-cost, well-known chips (the Game Boy being the ultimate case-in-point), and Genesis ran on reliable industry standards. Besides the 68000 core processor, it also included a Z80 sub-processor (the same chip used in the Game Boy). By relying on well-known, established tech, Sega made the Genesis a breeze to program for.

"The Genesis delivered an arcade experience, which differentiated it from that other classic gaming titan, the SNES. What differentiates the Genesis for me is the way its FM synthesizer sounds. Much credit is due to Yuzo Koshiro, of course -- particularly his '80s Detroit House-flavored Streets of Rage 2 soundtrack. It's rare that sound designers look to the music and sounds of a particular geographical location in order to build mise en scene. More than that though, the wheezy rattle of the Genesis sound chip had a futuristic feel to it -- the first gasps of the future of gaming technology."

Marc Halatsis

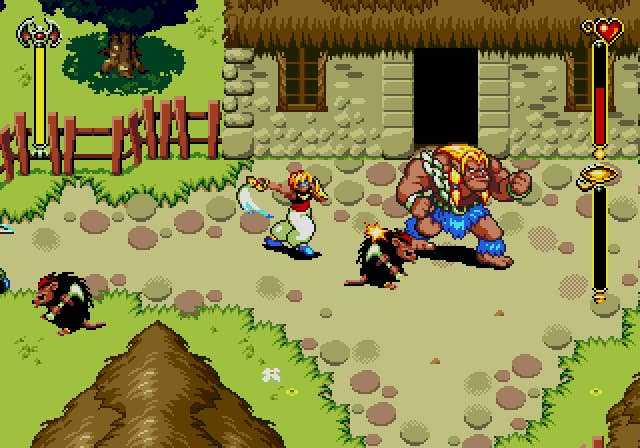

In fact, its architecture closely resembled that of most mid-to-late '80s arcade games. This was a brilliant move by Sega, as the concept of perfect arcade-to-home conversions still held tremendous sway in the late '80s. Genesis didn't waste any time showing off its arcade roots, quickly blowing away gamers with beautiful conversions of major hits like Strider, Super Thunder Blade, Ghouls 'N Ghosts, and The Revenge of Shinobi. While these ports weren't pixel-perfect, they absolutely demolished comparable offerings on competing consoles.

Japanese system, global success

Meanwhile, European developers were drawn to the system's similarity to Commodore's Amiga computers, producing a number of conversions and parallel releases that gave Mega Drive a leg up in Europe. The UK had shrugged with indifference at the concept of gaming consoles throughout the '80s, gravitating instead toward locally grown microcomputers like the Sinclair ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC. The Genesis, with its vivid graphics and raw electronic sound, caught many gamers' attention, even though Sega was ridiculously slow in bringing the console to launch in Europe.

"Whilst the U.S. had embraced the Atari and Atari-styled home consoles, the U.K. had never really caught on. If you had a machine that could play video games, it was probably a home computer like a ZX Spectrum or a BBC Micro, or maybe an Amiga. Around '91 or '92, Sega really pushed out its marketing for the Mega Drive. Arcades had never really caught on, so what the Mega Drive was capable of was really revolutionary. There wasn't much of the 'Nintendon't'-style advertisement, either; Nintendo wasn't really focused on Europe. By the time they started to get their stuff together, everyone -- and, more importantly, everyone's friends -- already had a Mega Drive."

Gord Allott

In fact, Genesis proved to be weakest in its own home territory. While it succeeded in the U.K. by awakening a nation to the potential of high-powered graphics and won the favor of Americans who were hungry for more authentic conversions of their favorite arcade games than the humble NES could offer, Sega never quite cracked the nut that is the Japanese console market. Why? Perhaps Nintendo simply had too strong a grip on the country, having effectively created its console industry with the Famicom.

Or, more likely, it wasn't Nintendo per se but rather the Nintendo style of game -- slower, deeper, less action-driven than Sega's arcade-inspired fare -- that appealed to Japan. Dragon Quest was bigger than Mario over there; yet despite a handful of strong RPGs like Phantasy Star IV and Shining Force II, the Genesis simply lacked the breadth and depth of adventure and role-playing titles Japanese gamers desired. Whatever the case, Sega managed to pry Nintendo's grip loose from the throat of the American gaming industry in a way many had long assumed would be impossible. Within a few years of the Genesis's debut, Nintendo's U.S. market share plunged from 90% to less than 50%. Super NES would ultimately claim majority control again, but only thanks to Nintendo's persistence and Sega's own screw-ups.

In some ways, the success of the Genesis would help cause Sega's downfall. The incredible performance of the machine under the eye of a foreign subsidiary reportedly didn't sit well with Sega of Japan; rather than seeing Sega of America's victory as an opportunity, they saw it as a threat to their authority and constantly pushed back against their overseas counterparts. This internal rivalry helped fuel poor business decisions and caused a lasting schism that played a significant part in the company's eventual departure from first-party status.

"I'd say there are two major reasons for Sega's inability to maintain the momentum gained on the Genesis. The first is that it confused the market in the U.S. By the mid '90s, you had two models of the Genesis, two models of the Sega CD, the 32X, the Pico, the Game Gear, the Nomad, and all the hype surrounding the impending release of the Saturn. The market was already clogged up with systems from multiple manufacturers and Sega overloaded itself. Not to mention the U.S. market was suffering a bit of a downturn at the time, probably due to the recent recession.

"Despite all that, I think that Sega may have been able to weather the storm had Hayao Nakayama not officially killed all 16-bit and 32X support in 1995 in order to concentrate on the Saturn. It was the best decision for Japan, but definitely not for the U.S. It seems like that decision had long-reaching effects on Sega's U.S. market -- [Sega of America president] Tom Kalinske left, Sega's internal studios were shaken up, in-development projects were killed or began porting to the Saturn, Sega of America basically lost power, and ultimately a very healthy-sized user base ended up abandoned."

Greg Sewart

Superiority through blackmail

But before Sega could fall, it had to rise -- and its ascent was impressive. Perhaps not surprisingly, it had just as much to do with third-party developers as with Sega's own projects.

Third party publishers, especially in the U.S., were eager for an alternative to the Nintendo Entertainment System. The NES's popularity made it clear to all that there was plenty of money to be made in console gaming, but thanks to a rigged licensing structure most of that money went to Nintendo. With unfavorable manufacturing and distribution terms, low accountability, and harsh limitations on quantities and titles, the NES licensee program sucked for everyone who wanted in on Nintendo's insanely popular system.

Sega initially intended to duplicate Nintendo's licensing system, but Electronic Arts forced their hand. Trip Hawkins and Bing Gordon assigned a team of engineers to reverse-engineer Genesis software and figure out a way to produce valid games for the console without going through Sega's process, then used the threat of offering their own much more favorable Genesis licensing program to other third parties (which would have destroyed Sega's business model) in order to negotiate a better deal. While being strongarmed like this must have infuriated Sega executives, it ultimately worked to their benefit. The more attractive terms of Genesis licensing versus what Nintendo offered for NES and Super NES drew publishers to the system in droves.

This was particularly true for American and European publishers, who had never managed to replicate the success of their Japanese counterparts on NES. Not only did Japanese third parties have a several-year lead on the machine over U.S. developers (who were initially reluctant to commit to console production after seeing the carnage that had ensued in the wake of Atari's collapse), but even after the west jumped in Nintendo's requirements put American developers at a disadvantage. Because the company insisted on manufacturing all NES cartridges in-house, in Japan, American publishers had to wait for their software to putter across the Pacific once produced, adding several weeks to the already hit-or-miss distribution process.

On the other hand, Sega's model was much friendlier to American businesses, and for the first time since the Atari era western developers were able to thrive in the console market. The NES may have given Japan its entrée into the global console market, but the Genesis made consoles truly international. Even some of Sega's key titles, like Sonic the Hedgehog 2, were developed in tandem with the U.S. team at Sega Technical Institute (which was headed by PlayStation 4 lead architect Mark Cerny).

We all scream ("SEGA!")

The American frenzy for Genesis was no accident, nor was it pure luck. Sega of America managed to secure an unusual amount of autonomy from its parent corporation, and it made use of this freedom to target its audience with laser focus.

The prevalence of locally created software certainly helped. After spending more than half a decade in exile on PCs, American developers were ready to make their return to consoles, and the Genesis offered a welcome door. EA definitely led the charge with its extensive library of licensed sports titles, and Madden NFL in particular went from hit to smash when it leapt from PCs to Genesis. But a fair few of the system's other big titles came from American minds, from the quirky (Toe Jam & Earl) to the juggernaut (Mortal Kombat).

In fact, with Mortal Kombat, Sega of America perhaps best demonstrated its canny understanding of the U.S. gaming audience. While both Genesis and Super NES played host to the arcade fighter, Sega allowed Midway to release an uncensored version on Genesis whereas Nintendo demanded most of the game's trademark violence and gore be excised. Sales of the Genesis release greatly outstripped its Super NES counterpart, and even more damagingly cemented the notion of Super Nintendo as the console for kids in many minds.

"Sega's moxie cultivated quite the passionate fandom, and for a while it was genuinely awesome to participate in. Unfortunately though, creators tend to attract the fanbases they deserve, and as Sega's substance has deteriorated, so has its fandom. It still seems to burble in a cauldron today. You can't cultivate a healthy fandom based on what's hip. You need to have real passion involved, and that means promoting the people who actually make games and working to keep them with your company."

Matthew Stone

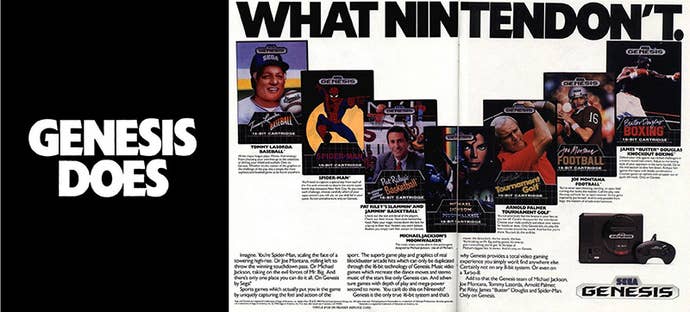

Sega parlayed Nintendo's safe, family-friendly reputation into an advantage. Its U.S. advertising was brash, loud, and aggressive. The company mocked its competition; no flaw in the Super NES was too minor for Sega's ad firm to turn into an attack point. For example, early Super NES games tended to suffer from slowdown as programmers learned to compensate for the console's comparatively slow CPU by playing up its other features; Sega presented Sonic the Hedgehog as something that could only have happened on Genesis and made up a catchy marketing term to promote the speed of its system. For millions of teens, Nintendo became the system your little brother played, because somehow Sega managed to sell the idea of a blue cartoon hedgehog as "edgy" and "cool."

"I'd say [Sega's] most important decision was to take on Nintendo openly with 'Genesis Does What Nintendon't' ad campaign as well as the subsequent campaigns directly comparing the SNES to the Genesis (showing the bigger library on the Genesis, comparing Sonic's speed to Mario, etc). It convinced [older gamers] that they were already thinking Nintendo was too kiddie for them and wow, look at this cool new system! Mortal Kombat was super-important, too. Allowing the blood and fatalities in that game wasn't only a great move from a consumer standpoint, but it helped create a bit of a media backlash against Nintendo's 'daddy knows best' philosophy."

Greg Sewart

Ironically, Sega's eagerness to embrace violence and gore ended up giving Nintendo one of its most effective weapons to counter Genesis's marketing. While Sega aimed for the hearts and minds of kids to convince them Genesis was cooler than Super NES, Nintendo aimed a little higher. Specifically, it aimed for the hearts and minds of parents, presenting the message that only Nintendo platforms were kid-friendly. Even if junior wanted a Sega system, mom and dad controlled the purse strings. Still, despite throwing Sega and the rest of the industry under the bus in front of Congress, Nintendo has never quite shaken the stigma of being the "kiddie" system... even 20 years later.

"The most noticeable influence the U.S. success had on the Genesis was the amount of violence found in the games. The Immortal, Sword of Sodan, Technocop, Road Rash, and many more games weren’t shy about letting the blood fly. I feel like Nintendo and NEC were just targeting 10-to-12-year-olds with their games while Sega knew rowdy teenage boys and adults would play as well. It worked for them; Sega's bloody version of Mortal Kombat nearly won them the console war."

Chris Iozzi

If the Atari generation introduced video games as a short-lived '70s fad -- the electronic equivalent of a Pet Rock -- and the NES generation established it into an enduring obsession for the young, Sega's Genesis began pushing the medium toward something resembling its contemporary form. Genesis was heavy on violence, on sports, and on image: Fundamental components of the engine that helps fuel today's console industry.

But Sega's sale pitch for Genesis also cemented the idea of choosing sides. Game marketing had encouraged tribalism ever since Mattel chortled at Atari 2600's stickmen and presented the "lifelike" quality of Intellivision's stickmen, but the console wars were never fought more passionately or by more fervent armies than in the 16-bit era. The market still skewed a little young for most players to be able to afford multiple consoles, and Nintendo's vastness made it an easy target for Sega's potshots. The gaming collective has never really outgrown that juvenile obsession with platform evangelism.

"The 'dudebro' appeal of the Genesis started as a really smart marketing move that simultaneously latched on to the trends at the time while also making Nintendo seem less 'cool' to the kids who were moving on to their tween and teen years. That image it built up, plus Nintendo's strict content policies at the time, lead to developers making exclusive titles for the Genesis that appealed to that demographic more in the form of 'extreme' sports like Road Rash/Skitchin', or games that made violence seem either grisly or cartoonish depending on the theme, like General Chaos or the Mutant League games. These games seemed so taboo at the time, which is why they were the ones I heard discussed at school or among my peers.

"It's hard to say from experience if Nintendo ever had the same appeal since most of my friends were Genesis kids, but lord knows they tried. You can make magazine ads showing Kirby as a desperate criminal or emphasizing the fart humor in EarthBound, but you can't hide that they weren't an accurate depiction of the actual game. Meanwhile, nothing cements the legacy of the Genesis' appeal more in my mind more than the Boogerman 20th Anniversary Edition Kickstarter, which is offering a green Genesis cart as one of the rewards despite the original game also having had a Super NES version. Because no one thinks of games like Boogerman as being on Nintendo, for better and for worse."

Adrian Sandoval

Subtractive add-ons

Sadly, Sega's grand accomplishments with Genesis would prove to be short-lived. While Genesis put up a great fight for several years, Nintendo fought to reclaim its market share little by little with key exclusives (notably Street Fighter II), graphical shenanigans (Donkey Kong Country), and simple endurance. But in the end, the blame for Sega's fall from the top rests most squarely on their own shoulders.

Simply put, Sega overextended the Genesis. While the core platform was strong, the company moved quickly to expand the system's capabilities with add-ons. First came the Sega CD, which added greater storage capacity, superior audio, graphical enhancements, and video playback to the system. Sega was hardly the only company to muddy its waters with a CD add-on in the early '90s; in fact, Nintendo was basically the only first party that didn't, and even then that wasn't for lack of intent.

But the benefits offered by the Sega CD had to be balanced against the fact that the add-on more than doubled the price (and complexity) of the platform. Furthermore, most of the top offerings available on Sega CD consisted of fairly niche material that, while well-regarded by history, didn't exactly leap off the shelves. Lunar: The Silver Star was a lovely RPG, but was it $299 for an add-on lovely? In the days before mainstream console gamers cottoned to nakedly Japanese pop culture, gems like Snatcher and Popful Mail relegated Sega CD ownership to a small, exclusive club.

Far less forgivable than the Sega CD, however, was the 32X. Whatever the intention behind the Genesis's second add-on, its combination of bad timing, poor messaging, and even worse software support felt like a slap to the face of Sega's most loyal fans. The 32X promised a power boost sufficient to make the Genesis competitive with the new generation of consoles (Jaguar, 3DO, etc.) cropping up in the mid '90s -- but at the same time, Sega was promoting its own next-gen console, the Saturn. A needless stopgap measure, the 32X ended up competing for fan dollars with the Saturn, and as Sega tripped over its own feet Sony swept in to build on what the company had accomplished in the Genesis's salad days.

And yet, even amidst Sega's strategic blunders, the Genesis soldiered on. Its software only grew more impressive over time, and the world's few Sega CD owners had access to some of the finest Japanese imports of the 16-bit era. Even more impressive was the Sega Channel, an online subscription service that basically worked like PlayStation Plus more than 15 years early.

"From my recollection, there really wasn't much the Sega Channel did 'wrong.' There was a good rotation of games each month, and generally in a really fair way. There were lots of holdovers for a couple months at a time to allow you to play through them (especially helpful with only one save file available at any given time), and then another batch of completely new material alongside them.

"It also felt like there were constant exclusives. I can remember playing Primal Rage, Earthworm Jim 2, and Vectorman well ahead of their release, not to mention gems like The Wily Wars which never saw a proper home release in North America. While Primal Rage wasn't exactly a showstopper, they did what they could with it, like a demo version leading up to a contest to see who could beat the game the fastest.

"Sega Channel was like a glimpse into the future: a relatively cheap monthly fee allowing constant and unlimited access to a catalog of games, new and old alike. Were it not for Sega Channel, I would not have discovered Shining Force II, whose soundtrack remains in constant rotation for me to this day. I had a chance to dabble in genres that I otherwise would never have even bothered renting. Perhaps the biggest thing working against Sega Channel, though, was its limited distribution. I consider myself extremely lucky to have been able to experience it. I saw the future in 1994, and it's only now that I feel we are even remotely approaching it again."

Michael Labrie

The Genesis legacy

While the triumphs of the Genesis tend to be overshadowed by the travails that Sega suffered in the years following the console's retirement, its successes shouldn't be diminished by its successors. Sega played a key role in ensuring the vitality and future of the games industry by breaking Nintendo's near-monopolistic hold on the U.S. and awakening the U.K. to the merits of television gaming. Even in Japan, where the Mega Drive duked it out with NEC's PC Engine for second place, Sega fostered variety and alternative choices for gamers.

The legacy of the Sega Genesis is best seen in its software library. As usual for Sega's consoles, its own internally developed projects hold up to the test of time. Meanwhile, third parties made remarkable strides on the system with both arcade conversions and great original material. Genesis gave birth to legendary developers Treasure. The relatively low production costs of Sega CD helped Working Designs establish itself as the first boutique publisher dedicated to niche import software. It served as the incubator for key modern sports franchises. Its intense, action-driven games remain addictive to this day, and its library of RPGs contains overlooked gems begging to be discovered by genre addicts. Americans got their first proper taste of Hideo Kojima's personal quirks with Snatcher, discovered turn-based strategy with Shining Force II, witnessed the glory days of vanished developers like TechnoSoft and Wolf Team, and maybe even played a few FMV games.

"Nintendo's platforms may be the home of my own nostalgia, but you can only play Super Mario World so many times. Playing the Genesis library is like a bizzaro-world late '80s/early '90 to a Nintendo fan. Many of the games have the same names but are completely different. The music sounds strange and mechanical, and there's a lot less pastel. Anyone who grew up in that time or appreciates those styles of games will find a lot of great things in the Genesis's library."

Jeremy Hasse

Two and a half decades after its debut, the Sega Genesis still holds a special place in many gamers' hearts. For the truly fervent, the console wars never actually ended, and Genesis will always be the superior choice over the Nintendon't-afflicted Super NES.

"Two things stand out to me about the Genesis's software. First, it was just as innovative, if not more so, than that of its peers despite having fewer buttons. The controller had the exact same amount of buttons as the NES, in fact!

"Second, the console is a good lesson and a warning to industry leaders everywhere: Don't get complacent. People never admire you simply because you are Nintendo or Sony or some other big name; they admire you because of what you did to give value to those names. Don't lose sight of that. Pay attention when your friends and partners start chafing under your restrictions because there will always be a Sega lurking nearby, ready to liberate your former allies from your oppressive rule."

Matthew Stone