Seeing Red: The Story of CD Projekt

Eurogamer's Robert Purchese explores how the Witcher dev went from a Polish parking lot to open world glory.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

I travel to Warsaw in Poland to visit CD Projekt, celebrated house of The Witcher, and there's one thing I discover that I can't stop telling people: The Witcher 2 was very nearly canned, and the entire company almost collapsed.

It was 2009, two years after the first The Witcher, and the global economic crisis had CD Projekt on its knees. The money from the first game had been burned trying to clear up the mess of The Witcher: White Wolf, the console game that never was. Elsewhere, the publishing-distribution business CD Projekt was founded on had become a black hole, sucking money away, and GOG was barely big enough to sustain itself.

It was the scariest moment in Marcin Iwinski's 20-year career. "The company is my baby, is my first baby," he tells me. "Then there is my daughter and then my son. And I realised that I might lose it."

Rather than hit the ground running after The Witcher, CD Projekt was about to fall flat on its face. "It was looking pretty grim back then. It was very edgy. We had probably a year where we were scraping money to make the payroll at the end of the month."

It's not what I expected, and not what I see before me now: Iwinski in a plush, dimpled leather chair in the middle of a trendy office, all exposed brickwork and glass walls and ventilation shafts, where some 200 people now work. There's a motion capture studio, a dazzlingly bright red toilet, suits of armour, swords, awards and a brand new vegetarian canteen. And all around me, an army is making The Witcher 3, a game so prestigious Microsoft boasted about it during the Xbox One conference at E3.

All this nearly... wasn't? "This was a few months of horror," Iwinski says. "And I don't know what happened, but at a certain point I realised that if this doesn't work I'll just do something else -- maybe I'll restart the company. And overnight the stress just went away and I had new power to do things.

"I don't know why this happens, it sounds extremely Buddhist, but there was something to it: as long as I was attached I was paralyzed. This is very much the approach we have to things: people can make mistakes, OK, but we have to learn from them and we cannot repeat them."

Iwinski would go on to help CD Projekt through a complicated but lifesaving reverse takeover which listed the company on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. And three months later investors were lining up. "It's totally against the logic but that's how it works."

This Polish Rocky of game development had rebounded off the ropes and was punching above its weight again. In only two games and a console port, CD Projekt rose from gutsy nobody into world beating somebody. But once upon a time there was nothing. There was just a boy called Marcin Iwinski living in the Eastern European "jungle", as he calls it, of Poland.

He loved games -- and he still does -- but when he was a boy it was almost impossible to buy them. The shadow of Soviet Russia and socialism loomed large. You couldn't buy those exciting computers Westerners were playing games on, not in Poland, and for most people, travelling beyond East Germany was a fantasy. But not for Marcin Iwinski's father, who produced film documentaries. He could travel, so Marcin Iwinski got a computer, and the Sinclair Spectrum had him at "10 PRINT 'Hello'".

"I was many times asked, 'Oh, so you were a pirate -- your roots are from the computer games market?' I say, 'Hey, for starters it wasn't illegal and second, look at a lot of the presidents or the founders or the key shareholders of IT companies in Poland now: who are these guys?'"

Marcin Iwinski

But he hungered for games, and there were no shops that sold them. Fortunately Polish copyright law didn't exist either, so computer markets sprang up in major cities at weekends, where games and computer bits would change hands for money. "It wasn't really legal," he shrugs, but there was no alternative so people turned a blind eye.

When he wrote a broken-English letter to a Greek man, whose address he'd found in the swap section of an imported Your Sinclair machine, he took his first steps towards his future career. He asked for games to be copied onto a blank tape and two weeks later he got them. "And I'm super happy. I arrive at the computer market over the weekend and I was a superstar. I brought new releases no one had before," he says. "I still remember one of the games was Target Renegade. It was an excellent game."

Then, two very important things happened. The first was Iwinski failing to qualify for a computer course he desperately wanted to take in high school, because this landed him in mathematical physics slap bang next to his future business partner of many years, Michal Kicinski, who was selling Atari games at the time. They hit it off immediately, "playing a lot of games, skipping school regularly."

The second very important thing was CD-ROM. "People who were not a part of this don't remember how revolutionary it was. I mean what is Blu-ray?" scoffs Iwinski. "[CD] was 400-something floppy discs on one CD; it was a total game changer."

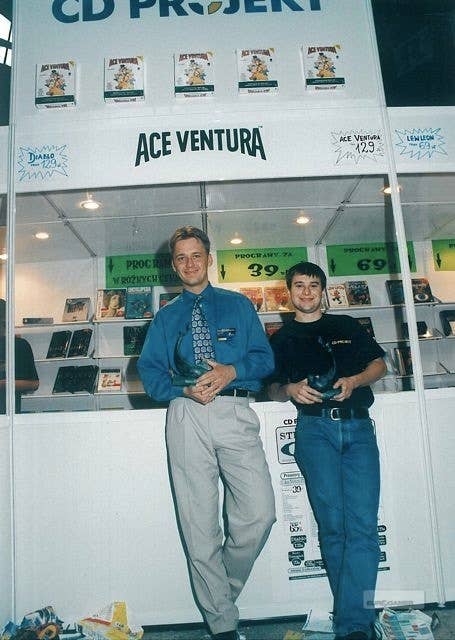

They imported games from small wholesalers in America to sell on in Poland -- and to play before everyone else -- games like Mad Dog McCree and 7th Guest. A business was born. "We went to the Tax Office and we knocked on the doors and said, 'Hey we want to start a company, what do you have to do?'"

The aptly named CD Projekt ("tseh-duh proiy-ekt", roll the "r") was formed in spring 1994. Marcin Iwinski was 20 years old. The two young men had $2,000 and a computer to their name, and their first office was a room in a friend's flat, rented for free. It was up so many flights of stairs that people would arrive for meetings drenched in sweat: "They were like huh huh huh [panting] -- where the hell are you?!"

"Funnily enough," Iwinski adds, "especially in Poland, I was many times asked, 'Oh, so you were a pirate -- your roots are from the computer games market?' I say, 'Hey, for starters it wasn't illegal and second, look at a lot of the presidents or the founders or the key shareholders of IT companies in Poland now: who are these guys?' These are the guys learning the ropes at the computer markets as well."

Not only was there nowhere else to come from, but those computer markets provided an important foundation for a core set of values that would serve CD Projekt for years to come. As it prepares The Witcher 3, there's a lot of love for CD Projekt -- but it's not blind adoration. It's appreciation of how CD Projekt goes about its business. Here's a company championing no DRM while others insist upon it; here's a company gifting additional content while others charge for it; here's a company respecting an audience rather than milking it. And it's all because of how the company grew up.

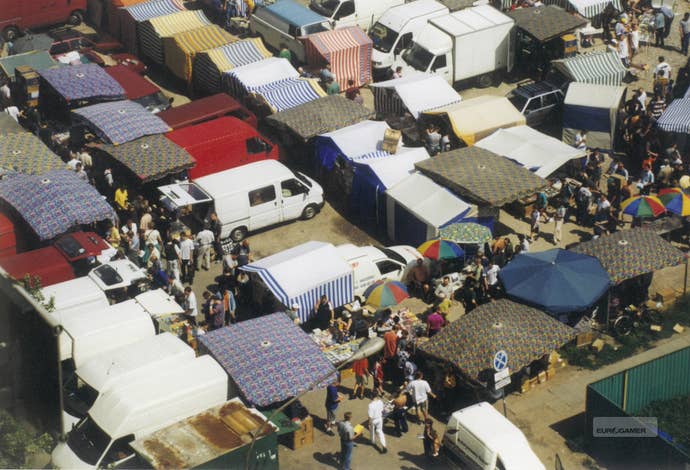

"Our main competition here in Poland was always pirates," says Iwinski. The national stadium in Warsaw -- a place rebuilt after the devastation of World War 2, and rebuilt again recently -- was home to Eastern Europe's largest flea market, and was Poland's largest exporter of counterfeit goods, game and music. "And," he grins, "you could buy a grenade launcher as well." You could pick up a pirated $25 computer game for $5, roughly 48 hours after release. "Kind of tough competition," he shrugs, not that there was anything he could do to stop it.

But what if he could convince people to buy a legitimate copy instead? He had an idea. "We made the biggest bet back in the day: we signed Baldur's Gate."

He knew it would be popular in Poland because it was a great game and he would localize it, something no one else was doing, so all the people who learned Russian at school rather than English -- as it was back then -- would be able to understand the game's hefty amount of text.

Best of all, Baldur's Gate being on five CDs meant even pirates charging $5 a CD would flinch.

It cost nearly $50,000 to licence 3,000 copies from Interplay, and localization cost the same again. Then there was marketing, physical production and the nice touch of hiring famed Polish actors to voice some of the game's roles -- another way of boosting popularity. "Back in the day it was a lot of money," he winces. "The whole company was relying on it."

Baldur's Gate cost the equivalent of $50 when it came out, which was expensive for Poland -- CD Projekt usually charged $25. But inside the box was all the added value a pirate wouldn't provide: a parchment map sealed with wax, a Dungeons & Dragons rulebook, sourced locally, and an audio CD. The cheapest pirates could sell the five-disc game was $25. Iwinski was hoping people prepared to pay that much would be prepared to spend even more for something special.

"Our core value is DRM-free and we will not sacrifice that."

Marcin Iwinski

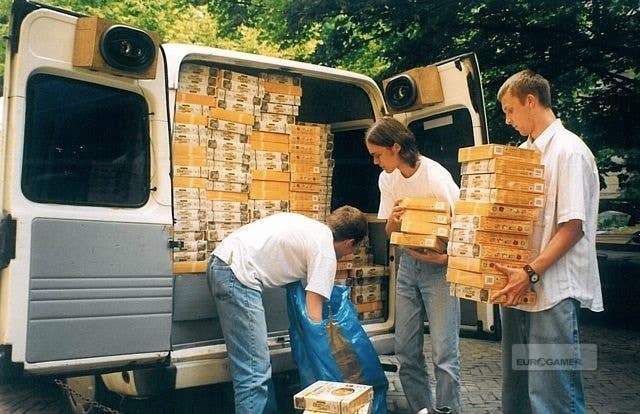

They were. Three months before release, orders way exceeded expectations. 5,000 became 6,000 became 7,000 became 8,000. "There wasn't even one retail chain in Poland handling games at the time, so it was orders from wholesalers, little shops here and there, computer markets. We had to take an external warehouse to handle it, because in our warehouse/office we could fit, tops, 5,000 units.

"And on day one we ship 18,000 units." It was a success that opened doors for CD Projekt around the world, and business took off. And it was a lesson well learned in the power of value.

Today, CD Projekt's digital distribution platform GOG no more tries to prevent online piracy than CD Projekt tried to prevent computer market piracy all those years ago. But GOG adds value to games by doing all the hard work, by finding and remastering games, by offering technical support, by bundling manuals, soundtracks, guides, and by striking a good deal. And there are no strings attached. "Our core value is DRM-free and we will not sacrifice that."

Adds Iwinski: "People have really silly ideas, and pirates are successful because they just do it right. It works, it's freedom, and OK it's free on top of that, but people want to pay for games and Steam has proven that, we have proven that. The real driver of success was listening to what gamers want, what they already do, and offering them this."

Five years after launch, GOG has 2 million visitors each month, and annual turnover has only just stopped doubling. And all that money, and all the money from a successfully relaunched online distribution business, referred to as CD Projekt Blue, gets pumped back into the main event: CD Projekt Red, the game maker.

"The idea was there from the very beginning," Iwinski says of making games. He tried when he was younger but discovered by the Amiga days that he was, he laughs, a "s**t of a programmer. But we really wanted to have our own game."

Baldur's Gate had gone part of the way there, and at the same time the "super adventure" of distribution-publishing in Poland was wearing thin. The excitement of blazing a trail had ebbed away as hassle crept in from newly created shop chains on one side and publishers on the other. Iwinski and Kicinski looked in the mirror and asked themselves, "Hey, do we really want to be just a simple box shifter?"

The nudge they needed was provided by famed games people Feargus Urquhart (Obsidian) and Dave Perry (Gaikai), who were at Interplay at the time. They wanted CD Projekt to take Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance to Poland, but it was a console game and Poland only did PC games. It wouldn't sell. "Well, why don't you convert it?" Interplay asked. "Yeah!" our Polish entrepreneurs responded. "We'll try."

The person they thought could handle the project was Sebastian Zielinski, Poland's star developer at the time, a man responsible for a Wolfenstein rip-off called Mortyr 2093-1944 -- a game slammed everywhere but Poland, where it was very popular indeed. He led the project but it was the second employee after him, a movie storyboard artist called Adam Badowski, who was the real catch. He is the studio head of CD Projekt Red today.

A PlayStation 2 dev kit was smuggled from Interplay's offices in London over to Poland, and work on Dark Alliance PC begun. But then the phone rang, and it was Interplay and the Dark Alliance deal falling apart. "But we already caught the virus," says Iwinski. They wanted to make a game, but what could they make?

There is no bigger fantasy license in Poland, a country steeped in medieval history, than Wiedzmin ("veedj-min"), or, as we know it, The Witcher -- actually an English translation created by CD Projekt. The books are written by Andrzej Sapkowski, a man with little love for video games, but with a fantasy so wonderful he's regarded as a Polish Tolkien. "That's what he means to us," stresses Iwinski. "He's just in a different league than anybody else. If you say 'Sapkowski' it means top class -- there is nobody else."

Such is his prestige that Iwinski hadn't even considered it likely he'd be able to sign the rights. But there they were, ripe for ripping from hands of a Polish mobile gaming company that wasn't doing anything with them. "We got in touch with [Sapkowski] and we ask: 'We heard that the game is really not happening and maybe we could talk?'" Sapkowski, a writer not a businessman, didn't seem to know what was going on. "You find out," was his answer. So they did. They told him the mobile game wasn't being made. "OK, make me an offer," he replied. So they did. "It wasn't a huge amount of money," recalls Iwinski, but it worked. "We got the rights and that's when the real difficulty started, because we had to make a game and we had no real idea of how to do it."

First things first: form a studio. Sebastian Zielinski's team became CD Projekt Red, and were based 120 km south of CD Projekt in Warsaw in a town called Lódz ("Wooj"). Quite the commute, and the reason Iwinski and Kicinski couldn't visit very often. But under the tutelage of this Polish expert, CD Projekt Red created a demo in a year. "It was a piece of crap," chuckles Adam Badowski. "We tried to convince Marcin and Michal not to go on the first business trip with the demo, but they decided..."

... to show it to a dozen publishers all around Europe on the most expensive and powerful laptop money could buy. "After two weeks of meetings we get two emails saying, in a very nice British way, 'It's not so good.' So pretty much: 'Boys, go home.' We were shattered. We were like, 'Oh my god we suck.'"

Sebastien Zielinski lasted about as long as that first Witcher demo. "One day I arrived with one of the guys at our Lódz office -- we told [Zielinski] before that we will be moving it to Warsaw and closing it down, and he said 'OK, I'm not interested'. We offered every single person a job and all of them took it. We took a huge taxi, we loaded the equipment and on the same day we moved it to Warsaw. And we put them in the warehouse." They've remained there to this day.

Michal Kicinski took over development and BioWare helped out with the Aurora engine, which had previously powered the Neverwinter Nights series. Iwinski was friendly with Greg Zeschuk and Ray Muzyka, and BioWare even went a step further, offering E3 stand space to the game if the demo was any good. It was, so BioWare did -- and The Witcher couldn't help but be noticed in the stampede for Jade Empire in 2004. In a twist of fate, that was also when BioWare announced Dragon Age, a series The Witcher will go head to head with next year -- only this time as an equal.

The Witcher 1, the game CD Projekt Red initially predicted would take 15 people to make, would end up taking 100 people five years to make, and cost an unprecedented 20 million Polish Zloty (the equivalent of around $20-$25 million in today's money, Iwinski believes). More importantly, adds Iwinski, "That was all the money we had. Plus some."

Poland had no game developers to fill the team with, and CD Projekt Red had no international pull to entice people from overseas, so bankers and doctors and people from all walks of life with a passion for games and trying something new were converted instead. But like CD Projekt Red, they didn't know what they were doing -- they were learning on the job.

Ideas spiralled out of control as the team tried to build something as complicated as Baldur's Gate and as epic as The Witcher fantasy. The game was cut two or three times but still they ended up with 100 hours of gameplay. "This just shows that probably, if we wouldn't have cut it..." 'What,' I interject, 'it would be bigger than Skyrim?' "No," he laughs, getting the reference, "probably more likely we would have been out of business."

Atari emerged as the publisher with the best deal (though Codemasters and Koch were in the running) and CD Projekt Red dug deep. "For half-a-year we were working 12-hour days every day, all weekends, all the time," remembers lead character artist Pawel Mielniczuk. And Adam Badowski was sleeping under his desk. "Really! For three days, in the same clothes. Stinky times," he chuckles.

"The game was a total mess," continues Mielniczuk, "and just at the very end it all came together. Actually it was amazing, because nobody was expecting that we will actually create a game from all the pieces scattered around." But from a standing start, from nothing, CD Projekt Red had. And in the autumn of 2007, The Witcher 1 was released.

"If you're a fan of compellingly realized environments, commendably realistic social interactions and full-blooded fantasy storytelling then pull up a pew," our sister site Eurogamer wrote at the time, "since The Witcher has a lot to offer."

It wasn't a masterpiece but it showed potential, and it was received warmly enough both critically and commercially -- it's sold more than 2 million copies to date -- to warrant a sequel. And this time CD Projekt Red could hit the ground running.

After the Enhanced Edition of Witcher 1 (offered as a free patch for existing owners, as with The Witcher 2), work started on two projects at once: The Witcher 2 and The Witcher 3.

The Witcher 3 was a background project to build an engine that would work with consoles, because BioWare's Aurora engine didn't, and consoles were a place CD Projekt Red always wanted to be. The plan was to move onto it after The Witcher 2.

The Witcher 2 would be built on Aurora again for PC, but it only got as far as a tech demo which, in those early days, Adam Badowski thinks "looked amazing". Brilliantly, this leaked. "We had a lot of leaks!" Badowski laughs.

The Witcher 2 on Aurora only got that far because at that point along came the big bad Witcher: White Wolf, which huffed and puffed and blew those plans down.

"I was ashamed at the time. We burned a lot of money -- our money."

Marcin Iwinski

White Wolf was to be a console conversion of The Witcher 1, and it was Atari's idea. Iwinski saw the logic in getting the brand established on console ahead of future games, so after initial reluctance he agreed -- a mistake, but how could he know that then?

CD Projekt Red didn't have the internal capacity to handle White Wolf development as well, so an impressive pitch won French studio Widescreen Games the job. CD Projekt Red wanted control, so Atari paid CD Projekt Red to get the game made.

After five months there were problems, and CD Projekt donated a dozen developers to the French studio to help out. Then more problems, and Iwinski began to suspect Widescreen's heart wasn't in it beyond being paid for reaching milestones. Adam Badowski had to fly down to help the studio crunch to produce an important vertical slice of the game for an Atari conference in Lyon, and it went down a storm, to cheers of "bravo!". But two weeks later there was another problem, and Widescreen wanted to push White Wolf back four to five months.

Enough.

"I'm not mentioning all the tensions, all the hours of stupid discussions on the phone, 'you are guilty', etc. The thing is, what we realised was they had no idea how to make it." More money was being spent on Widescreen Games each month than on CD Projekt Red in Poland. It was time for crisis talks, and to assess how bad the situation was.

"After five days of digging we sat down in a café in Lyon in the evening, we were probably five or six people, and said, 'What do you think?'" The answers grew increasingly worrying, one suggesting Widescreen would need another 30 people and an extra year of development to finish White Wolf. Then someone said. "Hey, let's cancel it and make another game! It will be easier than working with them." Eyes lit up. "The day after we told Atari we have to pull the plug."

Atari wasn't happy, and it was none other than big Phil Harrison (once of Sony, now of Microsoft, with an Atari interlude) who flew to France to hear both sides of the story. Iwinski remembers the meeting. "We were sitting on one side of the table, Widescreen Games on the other, and Phil," he says with emphasis, "in the middle. And we started fighting -- they started blaming us and we started blaming them."

A stern Harrison took Marcin Iwinski and Michal Kicinski aside, into a separate room. "And he said a very British thing like," and he imitates the accent, "'We are in real s**t here.' We were like, 'Yes Phil, we're sorry, we screwed up.'

"I was ashamed at the time. We burned a lot of money -- our money -- and then the next time I was in touch with Phil he told me that he is very very sorry but they have to send us a Bridge notice and we'll have to repay them the money that they gave us."

Iwinski flew to New York to negotiate and ended up signing over North American rights to The Witcher 2 years before the game had been made. "This would be repaying the debts for White Wolf," Atari had declared.

In May 2009, CD Projekt Red confirmed that work on The Witcher: White Wolf had been suspended. In reality, everything had been thrown in the bin -- nothing was reused. "We wasted so much time," laments Iwinski today.

On the back foot, CD Projekt Red scrapped The Witcher 3 and used the engine it had created to make The Witcher 2 instead. Only, the engine wasn't finished, so the first part of The Witcher 2 development was done blind, with nothing to prototype or test on. And then the global economic crisis brought CD Projekt to its knees, the scariest moment of Marcin Iwinski's career.

What's so impressive about this period of intense pressure is that Iwinski refused, even then, to take the easy way out and sign a quick deal with a publisher, jeopardizing the thing he cherishes most: creative control. The Witcher 1 took six months to sign to Atari because the contract wasn't right. Other new studios would have buckled, but Iwinski kept his head. Today, The Witcher 3 is funded entirely by CD Projekt. "We self-publish, practically."

The Witcher 2 took half the time to build that its predecessor did, despite being every bit as ambitious and with an engine to build as well. An entire location called The Valley of the Flowers had to be cut, even though it had "an amazing story plot". "It's not a girly place," Adam Badowski quickly adds, "it's a land of elves." And elves in The Witcher universe are as dirty and mean as everything else. The game's third act was also cut short because the team ran out of time.

But what was eventually released in May 2011 marked a huge improvement over The Witcher 1, and The Witcher 2 propelled CD Projekt Red into the big league. "There's simply no competitor that can touch it in terms of poise, characterization and storytelling," our sister site Eurogamer wrote at the time, "or the way in which it treats you not as a player -- someone to be pandered to and pleased -- but as an adult, free to make your own mistakes and suffer a plot in which not everyone gets what they deserve."

Better yet, it was achieved on the studio's own Red Engine, which would finally realize the company's console ambitions a year later on Xbox 360 (the studio didn't have the knowhow to tackle PS3 or the capacity to do both), with the Enhanced Edition of Witcher 2 -- a technical triumph, given what the studio managed to cram in.

Spring 2012, and soon another difficult decision loomed: "What are we going to do with next-gen?" And that was a while before anyone really knew what the consoles would be.

"But pretty fast we came to the conclusion that we want to make an open world game, a huge game, and what people expect from a game released by CD Projekt Red is an RPG with a great story that will also blow them away in terms of quality and graphics. And old-gen just didn't fit into that," says Iwinski. "We'd have to sacrifice so much and make a different game -- probably more Witcher 2.5. It was a no go.

"Back in the day it was a very brave decision, because a lot of the studios would be like, 'No!' Looking at it from a pure commercial view, it would be best to release it on all five platforms, but we wouldn't be able to make that game. It would be a different game; it wouldn't be this game."

So CD Projekt Red aimed high again, taking on multi-platform development for the first time and attempting an open world of a size that shouldn't be underestimated. The chunks of the game we've seen so far, however promising, are small portions meant to represent the whole -- there's still loads to do. How much? "I dunno!" blurts Badowski. "It's a simple question, a very general one, at the same time we have the production docs, everything, but the game isn't finished 90 per cent, it's not finished at all. But the whole storyline is set and implemented. Hard to say."

Around me the team is pushing towards "a very important deadline", a new section of gameplay, which will be shown to press first and then to the public. The plan is this year, although that's not in any way nailed down.

When will The Witcher 3 be released? It's a big secret, although I wouldn't expect it before the second half of 2014.

Whenever it comes, The Witcher 3 will mark the end of an era for CD Projekt, the end of more than a decade of using Andrzej Sapkowksi's world (what comes next, besides Cyberpunk, no one seems to know). It should cement CD Projekt Red as a big boy of game development, and The Witcher years will be remembered as a climb to greatness and a stepping into the limelight. But that light can be as unflinchingly harsh as it can dazzlingly bright, and no longer an underdog, CD Projekt Red will begin to feel the pressure of expectation.

But those days can wait, because next year Marcin Iwinski will be 40 years old, and it will be 20 years since his CD Projekt adventure began. He dared in those car parks all those years ago, and today he has achieved so much. He sits before me in a blue hoodie and jeans, a relaxed smile on his stubbly face, surrounded by a company not only continuing to set an example for Poland, but now the wider world.

"I feel very proud," he reflects. "The biggest success is that we've found and partnered with the most talented people. I want to say we've formed a family.

"Of course there are hard moments, as there are everywhere, but it's a very unique atmosphere. As long as it's here and we have the passion for games, and people are crazy talking about what they play, what they've seen or what comic they read, and not just pushing to deliver numbers on a daily basis, this will make sense.

"It's all about games and gaming."