Retronauts: The Continued Relevance of Isometric Games

A bird’s-eye view and large-scale battles ensure that gamers are still in love with isometric games.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In many ways, isometric games are representative of an entire generation of gaming.

So many seminal role-playing and strategy games of the 1990s—Diablo, Baldur's Gate, StarCraft, X-COM: UFO Defense, and more—use an isometric camera perspective that, to an entire generation of PC gamers, represents games becoming bigger, more tactical beasts. The following decade saw a sharp decline in the number of isometric games as developers shifted to emphasize larger on-screen characters in first and third-person games, but we're now seeing something of a resurgence—and their renewed popularity has less to do with nostalgia for old games than with the real and unique advantages this perspective gives gamers.

What we think of as isometric is really just a catch-all term for games that position their overhead cameras at an angle to display all three dimensions, where a top-down view displays only two. However, the term “isometric view” isn't technically accurate to describe the viewpoint in most of these games. Actual isometric perspective refers to a tilted overhead view where the three dimensions are scaled the same, but that ended up being surprisingly hard for developers to implement due to technical limitations of the time. What we see in games, however, is generally fairly close.

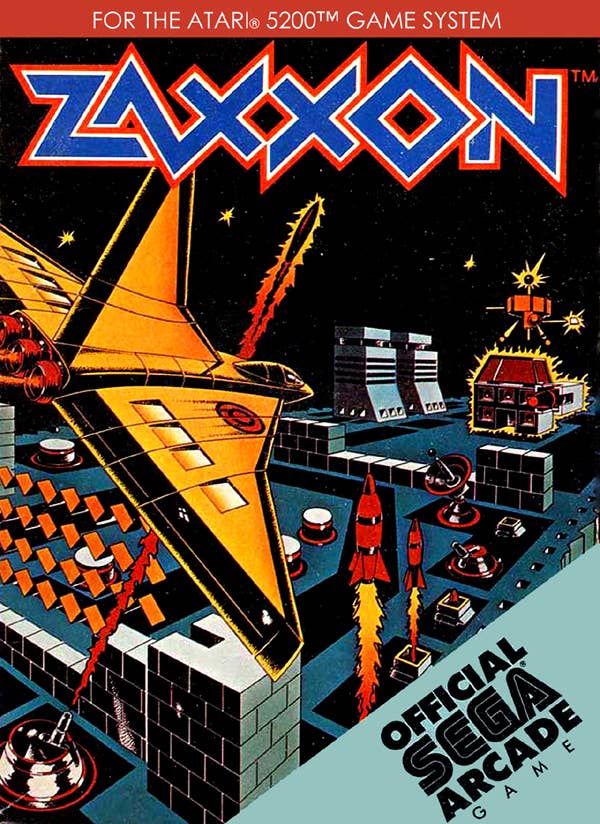

Beyond the many practical problems that isometric perspective solved, though, it originally came into being as a way to broaden what games were capable of at the time. The first significant appearance of isometric graphics in games came with Sega's arcade shooter Zaxxon in 1982. Its tagline, "Space games explode into a new dimension," was more than just marketing; it utilized projection methods to tilt the viewpoint and make you feel like you're piloting a fighter in three-dimensional space. This was huge, because until games like Zaxxon came around, viewpoints were mostly static and flat unless you were willing to work with vector graphics or complicated polygons. The depth isometric provides Zaxxon makes your ship truly feel like it's flying above the ground thanks to little details like the ship's shadow trailing just below. This also allowed the height your ship is flying at to truly matter given that, unlike overhead shooters, you could control the altitude of your ship, which mattered when it came to avoiding walls and aiming at grounded enemies. Both axes matter when it comes to aiming at enemies, a huge innovation that would soon spill over into other genres.

This new design would appear sporadically in games such as Congo Bongo, but it didn't become widespread until British microcomputer game Knight Lore from Tim and Chris Stamper (the brothers who would eventually form Rare). Much like Zaxxon, Knight Lore takes place in isometric environments meant to simulate 3D space. Here, though, you play as a knight who must explore a rather sizable castle in search of the objects that unlock the end of the game. The castle itself is divided into many one-screen rooms, another huge innovation never seen before—it predated The Legend of Zelda by a couple of years. Coupled together, these designs made you feel like you were exploring an actual world instead of moving from left to right along a painting. The depth isometric provides also allows for some platforming in the levels, a dimension The Legend of Zelda's overhead view was unable to pull off. Knight Lore inspired console action-adventure games such as Solstice, Equinox, and the Landstalker series, but it resonated most with microcomputer fans, and inspired a flood of clones, cementing isometric viewpoint as a computer game staple.

It wasn't long before a wide variety of PC game genres began using isometric design as the industry standard. RPGs like Baldur's Gate, Icewind Dale, Planescape: Torment, Diablo, and Fallout as well as strategy games like the Civilization series all became defined by their in-game perspectives. But they employed isometric perspective because it solved so many practical design problems. Angling the camera gives players a wider view of the landscape and allows more of the geography to fit on the screen at once.

"A well-executed isometric system should never have the player thinking about the camera. You should be able to quickly and intuitively move the view to what you need to look at and never consider the camera mechanics. Trying to run a full-3D camera while playing out a real-time tactical battle is certain to cause a helmet fire in new players as they are quickly overwhelmed by the mechanics," says Trent Oster, BioWare co-founder and current Creative Director of Baldur's Gate: Enhanced Edition with Overhaul Games.

The ability to see more of the environment inevitably makes handling a large party much easier. InXile's Project Lead for Wasteland 2 Chris Keenan describes the difficulties that an isometric camera alleviates: “Wasteland 2 is about turn-based combat with upwards of 10 to 15 characters on screen at a single time. Players need to take environment objects into account for visibility, cover, and height as well as pay attention to traps and enemies that are entering the scene.” And the increased field of vision compared to points of view that center on a single character can create situations and feelings in players that other methods simply can't match.

"Isometric games also allow you to swarm the player with monsters, really evoking the feeling of being overwhelmed, which would be frustrating in a first-person scenario," explains Leonard Boyarsky, Senior World Designer for Diablo 3.

But as we've seen, games like Baldur's Gate began to fade from the forefront of PC design soon after the turn of the century. As graphical power increased, developers placed more of an emphasis on intense action and character-driven interaction than geography-spanning conflicts, like with BioWare’s Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic. Most strategy games never abandoned an isometric-like camera, but RPGs and more action-driven games shifted to the player as the focus while abandoning larger-scale, party-driven skirmishes that required a zoomed-out camera, which made each individual character smaller on the screen.

"If you're writing a big-budget AAA 3D title, you want the player to really feel immersed in the action. You also want your fancy models and artwork to be drawn big on the screen so that the player can be impressed. The big-money games will always be drawn away from anything that makes the creatures and terrain elements small on the screen," Jeff Vogel, Spiderweb Software President and creator of long-running shareware RPG series Avernum and Geneforge, explains, providing a stark contrast between these AAA games and the kind of games his company makes.

Yet even in the face of that flashy, expensive competition, he's found an audience for the types of games he loves to make -- and he's not the only one. Everywhere you look, you see renewed interest in isometric perspective from both developers and players. Obsidian’s Project Eternity, which recently saw a highly successful Kickstarter campaign, wants “to bring back the look and feel of the Infinity Engine games like Baldur's Gate, Icewind Dale, and Planescape Torment, and an isometric-like perspective is key to capturing that look and feel,” explains Adam Brennecke, Executive Producer and Lead Programmer. The PC version of Dragon Age: Origins includes an overhead camera that was clearly patterned after the seminal isometric RPGs of the '90s like BioWare’s own Baldur’s Gate.

You're also seeing different types of strategy games that never stopped using the perspective continuing to thrive, such as Civilization. And, of course, as Dave Adams, Lead Level Designer of Diablo 3 reminds us, you have legacy franchises like XCOM and Diablo that continue to appear in the same viewpoint as they first debuted with “because Diablo is isometric. It’s the combat model – we love tons of monsters coming at the player from all directions, and then scouring the corpse-strewn landscape for loot, of course.” For many developers, isometric isn't a technical limitation, but rather a viable gameplay style.

Nostalgia certainly plays a role in why you still see isometric perspective, but attributing its continued popularity solely to rose-colored glasses does a disservice to what it can accomplish. As the technical need for its use diminished, it refused to become obsolete. Call it limited if you want, but games that use it prove it's a smart piece of design that stands the test of time.