Remembering Sega's First Console, the SG-1000

Remembering the SG-1000, the Japan-only console that served as the first tentative step in Sega's console dynasty.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Through the years, Sega has consistently played the Salieri to Nintendo's Mozart: Just as hard-working, every bit as prolific, but somehow unable to find that perfect spark of genius to catapult it to an equivalent level of fame. Although Sega has, at times, given Nintendo a run for its money -- the 16-bit era became all the more interesting for the vibrant enthusiasm with which Sega's Genesis shattered Nintendo's console market monopoly -- in the end, it just couldn't keep up. A little more than a decade ago, Sega's nearly 20-year run as a platform holder faded away as the legendary Dreamcast failed to overcome Sony's second PlayStation, and the company eventually accepted standard third-party publisher status.

Sega's was an uphill battle from the beginning, and their very first entry into the console market -- the 8-bit SG-1000 -- suffered from a combination of bad luck and short-sighted decisions. "The SG-1000 was a system that was up to the capabilities of consumer computers at the time that had the great misfortune of coming out on the same day as the Famicom in Japan," says former GamePro and 1UP editor Kevin Gifford.

The console game market was a different creature in 1983 than it is in 2013; midnight game releases didn't happen, and in fact there was no such thing as a dedicated video games section in most stores. Games had at some point migrated from the sports department to toys or electronics as the medium diversified beyond tennis- and ping-pong-inspired head-to-head amusements, but outside of an announcement in a newspaper entertainment column or a spread a few months after the fact in a computer magazine, the industry still didn't command an awful lot of press. The two systems' simultaneous day-and-date debut didn't have the same significance then as (for instance) the near-instantaneous arrival of Xbox and GameCube did in 2001.

Still, Nintendo advertised the Famicom quite vigorously, giving the system plenty of visibility among consumers. Furthermore, Nintendo had inroads with distribution thanks to its long history of marketing toys, dedicated Pong clone consoles, and the novel portable Game & Watch series. As a result, Famicom had a built-in advantage over the SG-1000 right from the start.

A good start isn't everything, though, and in fact Sega theoretically had a chance to catch up when Nintendo elected to recall early Famicom models to address a hardware defect. Sega's problem in the longer term, however, was that its hardware and business model simply weren't as forward-thinking as Nintendo's.

In a lot of ways, the SG-1000 represented a sort of last hoorah for the old ways. Everything about the system felt like a continuation of the business model laid down by Atari's 2600 and its competitors. On a hardware level, the SG-1000 effectively cloned the ColecoVision. The ColecoVision had been quite the powerhouse upon its U.S. debut in 1982; its hardware capabilities greatly outstripped those of the competition, and it sold (as well as it could, given its arrival into a saturated American console market on the verge of implosion) largely on the strength of the closest thing the world had ever seen to an arcade-perfect conversion of Donkey Kong. Sega's decision to work from that spec when designing their own entry into the console arena made sense; it put them at parity with the coolest machine available in the U.S., which was the world's leading home gaming market at the time of the SG-1000's development.

Unfortunately, Nintendo wasn't content to merely match their competition's standards but worked diligently to exceed them. The Famicom thus eclipsed the ColecoVision (and therefore the SG-1000) in terms of capabilities.

"From a hardware standpoint, the SG-1000 is very similar to a Colecovision," agrees Hardcore Gaming 101 editor Kurt Kalata. "For single-screen arcade games, the difference between a Famicom and an SG-1000 is not staggering, but the SG-1000 was terrible at games that required scrolling. If you compare Super Mario Bros. to the SG-1000 port of Wonder Boy, with its simplistic sprites and stuttering backgrounds, Nintendo's console totally shames Sega's on a very basic level."

Fittingly, it was once again Donkey Kong that provided the baseline comparison for the new system; impressive as the ColecoVision's version was, it didn't begin to compare to Nintendo's own conversion for Famicom. Not that anyone could compare versions of Donkey Kong with the SG-1000 in any case; after all, Nintendo wasn't about to license out their best piece of ammunition any further now that they'd entered the market. Sega was forced to debut their ColecoVision-like machine without Coleco's killer app.

"The SG-1000 had both inferior hardware and software," notes Kalata. "While Sega eventually became extremely popular in the arcade business, in 1983, their lineup wasn't up to snuff in comparison to Nintendo, who had a huge hit with Donkey Kong."

To compete, Sega shipped their system to stores accompanied by their own riff on the "guy climbs over obstacles in order to reach a gorilla" concept, Congo Bongo... but even then, it didn't make for flattering comparisons. While the arcade version of Congo Bongo boasted spectacular isometric graphics, Sega's home conversion was flat and ugly. Though vaguely recognizable as the same game, it didn't exactly instill confidence for a future filled with arcade-accurate conversions.

"Sega was in just as good a position as Nintendo, if you think about it," says Wired Game|Life editor Chris Kohler. "It was a popular maker of arcade games with some big domestic hits. I guess its games just weren't as impressive. The hardware always struck me as being rather underpowered than the generational leap that the Famicom provided."

Congo Bongo embodies a bigger problem with Sega's antiquated approach than merely the aesthetics and familiarity of the system's biggest titles. As Atari had demonstrated with the success of its 2600 against its technically superior competitors (and as Nintendo has proven time and again over the years), graphical power alone isn't everything. Sega's problem was that it adopted Atari's publishing philosophy, creating nearly all of the SG-1000's games in-house.

"Over the course of a few years, Nintendo gathered up enough third parties that the SG-1000 was annihilated."

In the days before Activision went rogue, Atari singlehandedly programmed every game for 2600, even titles licensed from other companies. When third parties appeared on the market, Atari continued to go it alone rather than collaborate with those other publishers. Sega took a similar approach, producing a large array of games in-house and converting licensed games internally (or with the assistance of uncredited "ghost writer" contractors like Compile and SIMS). Only a handful of SG-1000 titles came from third parties; by and large, even existing hits like Lode Runner and Galaga came from Sega itself.

Nintendo, however, completely changed the nature of console game licensing within a year of Famicom's debut by embracing third parties, turning would-be competitors into partners. "Over the course of a few years, Nintendo gathered up enough third parties that the SG-1000 was annihilated, an act which also spelled doom for its successor, the Sega Master System," says Kalata. But Nintendo's approach required a sort of forward-thinking mindset that Sega simply didn't possess.

But it made sense for Sega to take a less ambitious approach to the console market than its competition. After all, Sega hailed from arcade roots, and its console business was a side venture, not a primary concern, in the early days.

"Until the early '90s, more or less, Sega's main business was focused firmly on arcade sales," says Gifford. "Consoles were a second thought and something they did largely because they were a Big Video Game Company and that's the way the industry was going."

Sega's heart remained in the arcades, where they pushed both technical and design innovation well into the new millennium: Super Scaler sprite processing, the powerful Model 1 and 2 boards, custom hardware like Samba de Amigo's maracas, and more. While they did produce some very entertaining original console titles in the '80s, by and large they treated their 8-bit consoles as little more than a tool for bringing their coin-op hits into the living room.

Nintendo, on the other hand, committed completely to the Famicom. The system launched the same day that Donkey Kong spin-off Mario Bros. debuted in arcades, and the company produced only two more original arcade games after that: The unpopular Donkey Kong 3, and the obscure Arm Wrestling. That marked the end of Nintendo's forays into the arcade for nearly two decades; as the Famicom gained traction, Nintendo's presence in public game centers focused entirely on promoting Famicom and NES releases with time-limited coin-op versions of its most popular home titles.

But the same lack of focus that arguably undermined the SG-1000's fortunes also lowered the stakes of its performance. Because it supplemented Sega's arcade business rather than replacing it, its modest popularity -- it sold less than a tenth of what the Famicom accomplished in Japan -- gave Sega reason to continue slugging it out in the console space.

"In terms of sales, they would've been more than happy if they sold maybe 50,000 systems," says Gifford. "Such were the scales that the Japan market worked with before the Famicom. They wound up selling more like 160,000 in the first year, and even though that's far less than the FC and most people considered it a failure, it still beat their expectations a great deal."

Indeed, while it's easy to look at the SG-1000's low sales and minute library relative to the Famicom and declare it a failure, clearly that wasn't the case; Sega remained in the hardware business for nearly 20 years. Had their initial foray into the hardware market been an abject failure, they surely wouldn't have stuck around for so long.

It's probably more accurate to view the SG-1000 as a would-be powerhouse dipping its toe in the water -- a tentative first step. The SG-1000 may have been built around a dated business model, and it may have lacked processing power (not to mention a decent joystick), but Sega took careful notes and iterated on the machine in quick succession. The SG-1000 was followed by the SC-3000, Sega's take on the Coleco Adam and MSX, and the SG-1000 II, which added support for an inexpensive card-based media format.

Eventually, this experimentation led to the Master System -- which, incidentally, bore the name Mark III in Japan, directly referencing its roots in the SG-1000. Despite featuring considerably more powerful hardware than its predecessor (more powerful than the Famicom, too), the Master System maintained a link to its heritage with its card slot, which was built to support SG-1000 II cards. While the Master System never managed to make significant headway against the Famicom, it represented the company's more serious determination to take control of the console market, an ambition that would come to fruition with the Genesis.

Were the SG-1000 the beginning and end of Sega's console dynasty, it would go down in history as yet another obscure failure from the chaotic early days of video gaming. Instead, it's something more important: An obscure not-quite-failure that gave Sega entrée into the soon-to-be-revitalized home games market. As a standalone machine in its own right, it offers little remarkable.

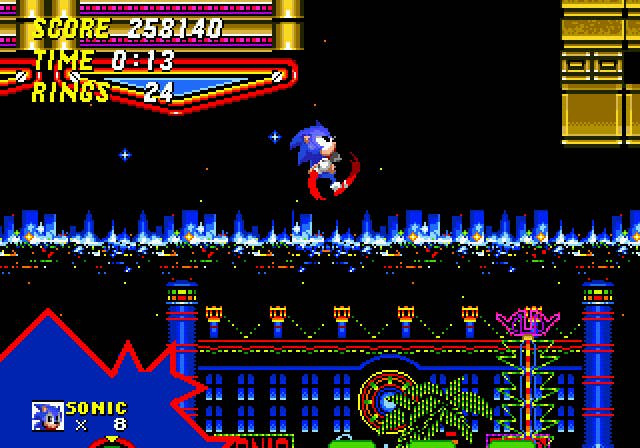

"It's really nothing but a historical curiosity now, as Sega's first game system," Kohler declares. But that's no bad thing. As the basis for a legacy that includes the likes of Phantasy Star, Sega Saturn, Sonic the Hedgehog, the Dreamcast and more, it's truly the germ of something wonderful.