Remembering Nintendo Power, the Pravda of Video Games

25 years ago, Nintendo dressed naked sales pitches in the trappings of journalism, and millions of children rejoiced.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Sometime toward the middle of 1988, something fantastic happened for three million kids who had noticed the product registration card in the Nintendo Entertainment System they'd received for Christmas a few months prior: A free magazine showed up in their mailboxes.

This wasn't just any old magazine, though. It was the premiere issue of Nintendo Power, nearly 100 pages crammed full of screenshots, artwork, previews, tips, and features dedicated entirely to games for their NES. And for a modest sum, kids (who dutifully asked their parents, of course) could subscribe to the magazine and be assured receipt of a similar stack of information every other month.

Sure, it was thinly veiled advertorial; endlessly effusive coverage of games with nary a critical word inserted edgewise comprised the sum total of Nintendo Power's content, and you had to look really hard to find a hint of snark or lack of enthusiasm for even the most mediocre piece of software. But that was perfect for the audience. Nintendo Power mostly sold to kids for whom the NES was their first-ever gaming experience, or the first console they owned, or who had weathered the Atari crash and hungered for new and exciting experiences outside of arcades. The NES audience 25 years ago didn't want to hear what was bad; they wanted to hear what was cool, what they should be excited about, and why their purchases were totally justified and brilliant. You know, exactly the same as today's console fanboys.

Unlike other game companies, Nintendo has always operated under a closed, insular business model. Nintendo Power was one of the first times we truly saw that style in action -- and the first indication of how effective it can be when executed properly. Nintendo Power focused entirely inward on Nintendo products, promoting only software for the company's platforms and giving first priority to first-party software launches. Much like Nintendo's hardware business, their in-house magazine served their own needs first and foremost and offered a far from egalitarian platform for third parties.

Yet for those proselytized into the Nintendo way -- which, let's be honest, meant most '80s kids who liked video games -- Nintendo Power's singular focus was perfect. Young gamers who owned an NES and could afford to buy only a few games each year didn't want to waste their time and money on magazines highlighting computer games or a section of screens of games on sale in Japan. They wanted information on the system they owned, details on games they could (and should!) own, and Nintendo Power offered those things and nothing but.

Nintendo Power also represented a microcosmic view of the Nintendo software ecosystem on a less obvious level. Much of the magazine's content (and even its design) was handled in Japan, with its American staff collaborating closely to tailor the content and design for the U.S. audience. Nothing about the magazine overtly screamed, "This was made in another country," but its garish design and jumbled layouts adhered closely to the Japanese periodical aesthetic that defines the country's gaming magazines to this day. Not surprisingly, NOA President Minoru Arakawa had conceived the Nintendo Power brainchild after being inspired by imported publications such as Famicom Tsushin (aka Famitsu).

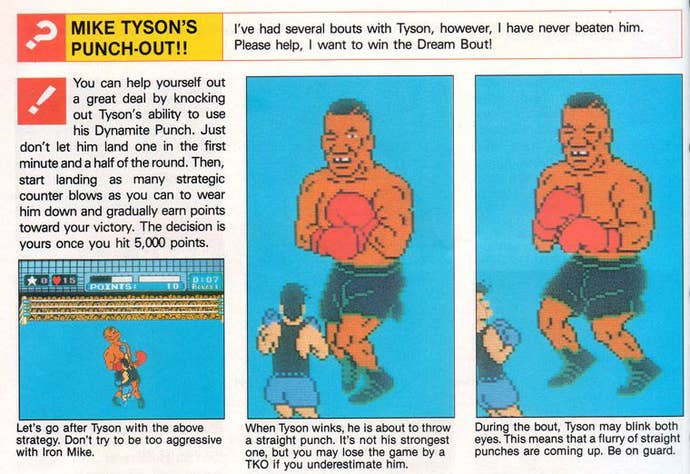

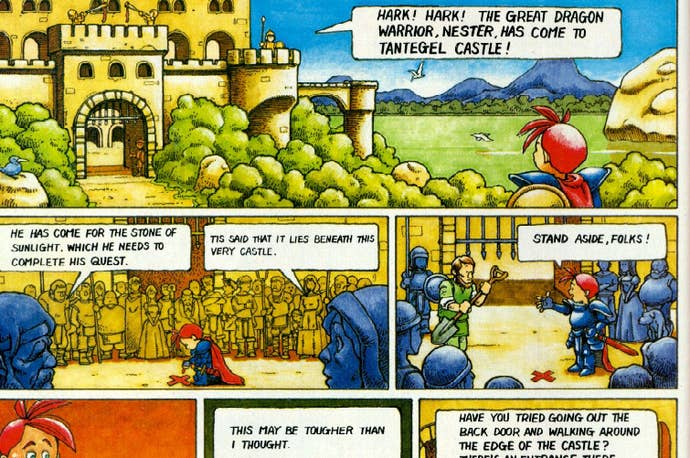

Where Electronic Gaming Monthly cheerfully swiped Famitsu's four-man "cross review" format, Nintendo Power's appropriation of the Japanese publishing discipline ran deeper. Features like its tips-and-tricks section, its expansive game maps (built from screenshots captured painstakingly in an era before emulation and digital video), and even goofy cartoon features like "Howard & Nester" echoed Japanese publishing tendencies despite having been crafted specifically for American readers. Top-flight Japanese illustrators like Katsuya Terada and Shotaro Ishinomori (of Cyborg 009 fame) contributed regularly to the magazine well into the 16-bit era, bringing into play unusually high-quality artwork that didn't come off as overtly anime-like (a style which, NES publishers strongly believed, was so deeply offensive to Americans that they were better off changing anime-style box art into ugly, amateurish paintings).

At its debut, Nintendo Power in many ways represented a culmination of Nintendo's existing publishing experiments, the Fun Club Newsletter and the Nintendo Player's Guide. The former took the form of a bimonthly newsletter (initially printed with two-tone ink but ultimately evolving into a glossy, full-color publication produced at considerable cost) that essentially read like Nintendo Power in miniature, highlighting upcoming games and offering tips and strategies for popular titles. Add to that format the essence of the Player's Guide, which laid bare the secrets of the system's best early-era releases (Kid Icarus, Castlevania, Metroid, etc.) through extensive maps, and the science of the magazine fell efficiently into place.

A gallery of Nintendo Power covers during the NES era represents a lineup of the finest 8-bit classics the system had to offer, with only a handful of duds breaking the streak

Surprisingly enough, you'd be hard-pressed to find serious criticism of the early years of Nintendo Power online. While its contemporary publications tended to brush it off (one roundup in a mainstream news periodical memorably described its design as "peanut butter-and-jelly layouts") and not take it seriously, its target audience -- the NES faithful -- loved it. The fact that it was decidedly one-sided, a step removed from advertorial, didn't matter. Nintendo Power preached to the choir, and those who hadn't been indoctrinated simply ignored it.

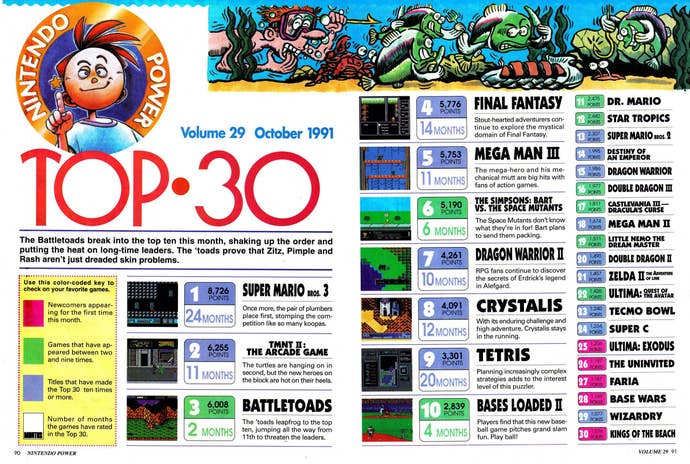

Perhaps this respect (or lack of disrespect, anyway) comes from the fact that despite its promotional nature, Nintendo Power had a remarkably amount of editorial integrity. For years, the book eschewed paid advertising. Of course, the periodical existed entirely to sell kids on NES games, yet the leads behind the magazine -- editor Howard Philips and Nintendo Vice President of Marketing Gail Tilden -- ran the coverage plan as a meritocracy. As they explained to Gamasutra, before being included in the magazine, each NES game first had to be evaluated through a "power system" that determined the "heat" each title generated among players and professionals alike. Licensees could beg all they wanted, but ultimately Nintendo Power focused on games whose quality and appeal held up; as such, the book effectively curated the system's highlights.

A gallery of Nintendo Power covers during the NES era basically represents a lineup of the finest 8-bit classics the system had to offer, with only a handful of duds breaking the streak. The inner pages admittedly tended to be a little less discriminating, with previews and even post-release coverage for obvious junk (e.g., LJN's dreadful offerings) penned by writers whose frustration becomes clear with the hindsight of adulthood and a proper understanding of irony. Still, truly poor NES games could only ever hope for a small box-out in the upcoming releases list at best, or perhaps a sympathy cheat code somewhere down the road. Nintendo Power curated the greats in expansive spreads and downplayed junk software through omission.

Nintendo Power's nature changed over the years as Nintendo's hammerlock on the U.S. gaming market weakened. As Sega's Genesis assaulted the company's American monopoly with both withering commercials and soaring sales, Nintendo Power shed its friendly NES-era trappings and took on a harder edge, with louder design, bolder colors, and even more aggressive typefaces. The transition into the 3D era saw Nintendo Power go into full propaganda mode, trumpeting Nintendo's official marketing line to ignore competing consoles like PlayStation and Saturn until the N64 finally launched and it was at last time to "change the system." While the magazine had always existed as a marketing mouthpiece -- its title reflected the company's NES-era tagline, "Now you're playing with power" -- that fact grew more evident as Nintendo's dominance slipped and its blinkered focus on Nintendo products began to ring false, like a state-run paper that echoes the hollow propaganda of a crumbling regime.

Still, even if its ulterior motives consisted entirely of building sales, Nintendo Power stood as a valuable ambassador and tool for discovery in its prime. Among other things, the magazine made a heavy push to promote role-playing games and other niches. Clearly Nintendo hoped to recreate those genres' success in Japan, but thanks to its constant emphasis on the likes of Dragon Warrior and Final Fantasy (and eventually the launch of a regular RPG column that even highlighted import-only titles) countless gamers discovered a style of game they might otherwise have ignored. Even brief blurbs for quirky mid-tier titles like River City Ransom and Golgo 13 lent them an air of intrigue that encouraged many players to investigate them.

Eventually, Nintendo's marketing ventured in a different direction as DS, Wii, and the so-called Blue Ocean deprecated the core gamer who had comprised the Nintendo audience for so long. The company handed over the reins of the magazine to Future, who revitalized Nintendo Power for several years until Nintendo elected not to renew the NP license. The magazine wheezed its last breath last year, and though self-published enthusiasts aim to take up the torch, no magazine will ever quite be like Nintendo Power... both for better and for worse.