Reanimated: The Story of Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodlines

Eurogamer's Rick Lane looks at the troubled RPG and how fans kept it alive long after its developer abandoned it.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

On November 16, 2004, two games powered by the Source engine were released for the PC. The first was quickly heralded as a modern classic, leading to its creators becoming one of the most influential companies in the games industry. The second was largely ignored, resulting in the closure of its developer and the scattering of its designers to the winds.

"It was dumped on the market at the worst possible time - most people didn't even know we were out," says Brian Mitsoda, the former lead writer on Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodlines "Both fans and the Troika devs are always going to wonder what the game could have been like with another six months."

Bloodlines was sent out to die. An unfinished game released prematurely by its publishers Activision, it didn't stand a chance on the shelves, especially alongside the hotly anticipated Half Life 2. But the commercial death of Bloodlines wasn't the end for the game. Thanks to a German analytical chemist with a passion for fixing broken things, Bloodlines has received not six months of additional work, but nine full years.

This is the story of two men who breathed life into the same game - one before it was born, the other after it died.

Troika Games was founded in 1998 by Jason Anderson and Leonard Boyarsky, and work began on Bloodlines in November 2001. Mitsoda joined Troika just under a year later, after a spell at Black Isle Studios working on Torn, an ambitious RPG running in Monolith's 3D Lithtech engine. Development of Torn was cancelled in 2001, and Mitsoda was attracted to Troika after hearing about what they were working on.

"They were still a garage developer when so many studios were becoming factories, and they were making full-fledged RPGs," he explains. "I got really excited when I saw what they were doing with both the White Wolf license and the setting, and I made them quite aware of how intrigued I was to work on the project. Apparently, they thought I was a good match too and I was hired that night."

Mitsoda was employed as lead writer on an RPG at a time when RPGs were enjoying critical success after critical success. In the three years prior to Bloodlines' initiation, Baldur's Gate, Planescape Torment, System Shock 2, and Deus Ex had all been released, and they all shared many commonalities. Many-layered systems, expansive worlds with broad player choices in how to explore and interact with them, and fantastic writing.

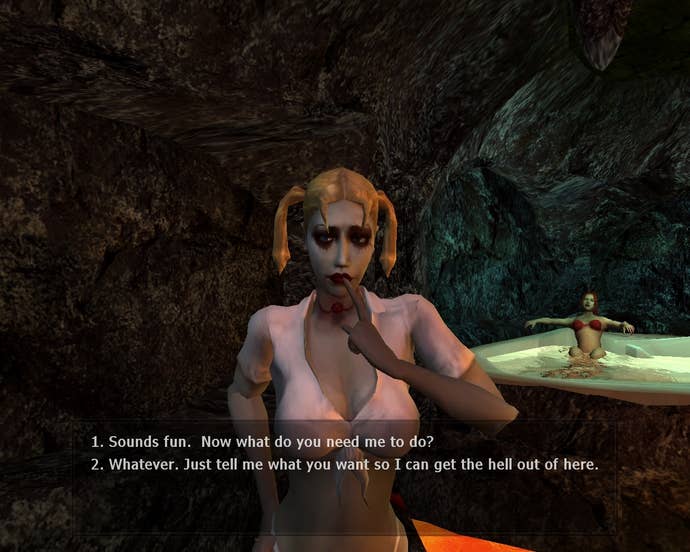

Bloodlines seemed intent on outdoing them all. The Troika team approached the project with what Mitsoda has previously referred to as "kitchen sink design". The game featured four huge hub-based environments with many more enclosed levels sprouting from them. It included both melee and ranged combat, a stealth system, nine playable races, seven classes, four types of dialogue influence methods, and a sprawling, many-threaded story with a distinctly adult blend of humour and horror.

"We were told to wrap it up in a matter of months at a point where we knew that was going to require a lot of crunch. It was obvious we weren't considered a very important project anymore."

Brian Mitsoda

"It's flat out depressing just writing characters who keep reiterating how shitty their lives have become," Mitsoda says, "There's got to be hope occasionally, a feeling from a character that good might triumph - right before they get killed with a tree trimmer, preferably."

A frequently cited example of the scale of Bloodlines' ambition is the playable Malkavian character. Sired into the world with the double-barrelled problem of being mad as well as undead, the Malkavian sported an entirely different script to the other eight playable races. But Mitsoda points out that the writing the Malkavian was actually one of the least trying aspects of development. "It was, like most things, more work than we probably thought it would be, but I loved the change of pace for them. It wasn't too terrible to do the Malk lines, simply an additional column to change up answers or add additional ones in the dialogue tool."

More problematic, according to Mitsoda were the other, non-playable characters encountered throughout the game, particularly due to the fact they were all fully voiced and animated using Source's revolutionary animation system. "I had a lot of fun and frustration writing the Prince because he was such a massive character, but he was a lot riskier, I think, because without the right voice (Andy Milder), he could have been less complex, more heavy-handed."

Although the Source engine helped bring life to Bloodlines' characters in a way no RPG had witnessed before, it also brought its own difficulties to the project. The engine was still in development at Valve in tandem with the creation of both Bloodlines and Half Life 2, meaning the developers were working with new, largely unfamiliar code and tools with only one source of support if things went wrong.

While this had minimal effect on Mitsoda's writing duties, it is something he remains wary of to this day. "I don't really want to work with tech unless the tools for designers are there, the engine isn't in beta, the costs for the engine aren't a barrier, and that we can iterate on our tech for future projects," he states. "I really think the biggest drawback of AAA tech is that the design tools aren't keeping up with the graphics quality. If I need several dozen people to make any significant changes to your engine, it's useless to me."

The combination of unfinished technology, runaway ambition and a perfectionist attitude which led to reams of work being mercilessly scrapped meant progress on Bloodlines was painfully slow. After three years of development with no end in sight, Activision gave the team an ultimatum. "We were told to wrap it up in a matter of months at a point where we knew that was going to require a lot of crunch. It was pretty obvious at that point that we weren't considered a very important project anymore."

Troika did their utmost to ensure the game was release-ready, but it wasn't, and while Bloodlines was rightly praised for the quality of its world buliding and writing, the holes were obvious for all to see. Shortly after the release, most of the development team was let go, and those who remained spent Troika's final few months in a confused state between trying to plug the leaks in Bloodlines' code and outlining a new project that might hopefully save the company. "We were glad the game came out, but we weren't thrilled with the state it was in. We had no other projects signed and we were crunching on prototypes and pitches to try and get the team onto another game before the doors closed."

Bloodlines' release on the same day as Half Life 2 undoubtedly played a part in its commercial failure and the eventual closure of Troika in February 2005. But the game which stole Bloodlines' spotlight also played a small part in its redemption. While Bloodlines was failing to sell, Werner Spahl - an analytical chemist at the Univeristy of Munich - was enjoying Valve's masterpiece. "I mostly only played first person shooters at the time. But I liked the Source engine and thus just had to try Bloodlines, which was the other main Source engine game then."

Spahl, known online as Wesp5, grew up modding and patching existing games with his brother, creating an improved version of the Atari ST game Midimaze named Midimaze Plus. By the time of Bloodlines' released he'd also worked on modding projects such as Xen Warrior for Half Life and Theme Doom. Having mostly only played shooters, Bloodlines variety and depth fascinated him in spite of its flaws. However, the idea if patching Bloodlines didn't occur until he installed the community patch created by Dan Upright.

"It broke my game!" Spahl says. "So I contacted him and asked for a fix, to which he replied he was finished with the patch and that I should do it myself. He then explained me how, and after fixing the problem, I asked him if I could continue the patch to which he agreed."

Spahl took over the patching duties from version 1.2 onwards. Despite two official patches from Troika and two unofficial patches from Upright, there remained a vast amount which needed to be fixed. Indeed, Spahl didn't actually have time to playtest the game himself, instead relying upon the Bloodlines community to report bugs and other issues. Sometimes the community would assist with fixing the game too. "There are people who helped more, like spell-checking dialogues, adding Python scripts, fixing specific .dll code problems, correcting models or even creating maps."

"It annoys me very much that some gems like Bloodlines failed because they didn't get the hype that larger blockbusters get or were released unpolished or unfinished."

Werner Spahl

Even with the support of the community behind him, fixing Bloodlines' many problems wasn't easy. Alongside the sheer size of the game, its complexity meant that fixing one element of the game often resulted in breaking another. Furthermore, while fixing a scripting bug here and there was relatively straightforward, delving deeper into the game's DNA offered up challenges of its own. "Everything connected to the basic level geometry or the models is very hard to fix, because there is no real SDK. You can only do so much by changing level entities, and for errors regarding models I often had to get outside help."

As time went on, and Spahl became more confident working with the Bloodlines' code, the unofficial patches went beyond simply fixing obvious problems, and began to restore cut content and finishing unfinished content. In patch version 8.0 Spahl restored a guard character to the game after finding his dialogue file. He used a script in the game's map to locate the guard's position and asked a member of the community to record the voiceover. The most substantial addition came in version 8.4, when with the help of the community Spahl restored an entire level to the game. "Our biggest achievement is the recreation of the cut library map which we basically had to build from scratch while using all the models and textures belonging into it, which Troika left us in the game files."

In fact, Spahl's patches have altered the game so much from its original state as to result in some criticism from the community, so now there are two versions of the patch, a basic one that performs straightforward bug-fixes, and an advanced version that restores content and tweaks many aspects of the gameplay.

Nine years on from the release of Bloodlines, unofficial patches are still being released. The latest, version 8.6, was released in April this year, and Spahl intends to keep patching the game "as long as people report bugs that I can fix and there is still stuff that we can restore." But for all of Spahl's efforts, the game will never be finished. There is already a list of issues which Spahl simply cannot fix, which begs the question: why? Why spend years of your life on a project that can never be finished?

"First of all patching, and especially restoring stuff, is sometimes much more fun than just playing the game, because it is active and creative," Spahl answers. "Second, it annoys me very much that some beautiful gems like Bloodlines failed because they didn't get the hype that larger blockbusters get or were released unpolished or unfinished."

Meanwhile, after working on the spy-RPG Alpha Protocol, another ambitious yet troubled game, Mitsoda has founded his own development company and is heading production of Dead State, which, oddly enough, is looking to recapture the development experience of Bloodlines. "It's about going back to basics - a small team that loves RPGs, making a classic RPG. We may not all be in the same location, but it still feels a lot like Troika did," he says.

"It would also be nice if we could keep the lights on after the game ships," he adds. "That's one bit of the Bloodlines experience that I would hate to replicate."