Peter Molyneux and the Godus Delusion

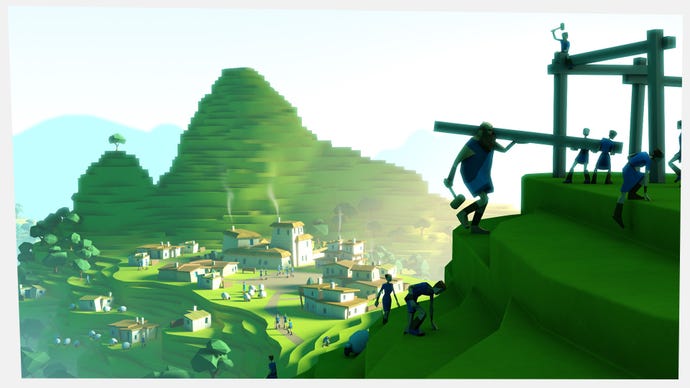

Eurogamer's Martin Robinson examines how 22cans' evolving game is looking to win back early doubters.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"You're going to go away and say that f**king bastard, he's promising stuff all over again."

Whatever you've got to say about Peter Molyneux and the ongoing development of Godus, his return to the genre that helped make his name, we can likely all agree the developer's at least got a wry sense of himself.

It's no doubt helped him through the turbulent development of a project that he left Microsoft to pursue, and that's slowly, sometimes messily, come together in the two years since his departure. What started with the experiment Curiosity evolved -- via Kickstarter -- into Godus, a hyper-connected take on Populous formula.

The problem was, when Godus hit Steam Early Access last year, its biggest feature was entirely absent, and what was left was hardly inspiring. "You move across the terrain cancelling out mountains and filling in valleys," wrote Chris Donlan in our sister site's alpha review. "Before you lies paradise, behind you trails an endlessly unfolding slab of neolithic car-parking. You're God, and God seems to want to recreate Sittingbourne town center, circa 1978." [Our American readers may be unfamiliar with Sittingbourne town center circa 1978, but we're sure you can use your imagination in this instance -- USG]

Godus 2.0, which launched earlier this year, introduces some of the features that look to remedy the situation. Voyages are now an option for your followers, with connected hub-worlds that see players move up tier-by-tier until the very pinnacle, the God of Gods, are being folded in, and the game is being prepared for limited release in Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, the Philippines and Sweden before being rolled out elsewhere.

Speaking to Eurogamer at last month's GDC, Molyneux laid out the plans for Godus, its struggle with the damage done by free-to-play games and the criticism it's come in for since launch.

You were clear about it being early access -- but even taking that into consideration, the reception hasn't been positive. Did that take you by surprise?

No, it didn't. This is the world that we live in now -- you can't keep all the people happy all the time. You can say -- and if you look at our Steam page, the first thing it says is that this is not a finished game, it has bugs and it's going to change rapidly, it says that in bold -- you can say that, the fact that no-one reads these things. They get it, they play it and say that's not good enough, and it's not what Peter said when he first introduced the Kickstarter video. The purpose of what we're doing is trying to make a great game. And to make a great game, sometimes you have to upset people, sometimes people will say, oh -- there's this fanatical, almost paranoid fear of mobile that PC gamers have, which is crazy. Because mobile is a fantastic gaming device. But they feel that free-to-play is the most toxic, radioactive thing that's going to destroy games. They feel that no game on touch is worth looking at. That's because us gamers have been abused by Facebook gaming and mobile gaming for so long, but that doesn't mean we shouldn't do it. There's been a lot of negative push-back from people saying they're scared that Godus is going to come to mobile, and we're going to turn into these analytics-driven monsters.

I think a lot of people's issues with Godus weren't about it being buggy though, but about it being fundamentally boring.

It was boring because we only gave you the two things in the game -- we gave you sculpting, and we gave you a little bit of expansion. We hadn't turned on the voyages, and we hadn't turned on the big motivators that motivated you to do these things. We couldn't do that because we had to refine that sculpting mechanic, we had to refine the AI of the world and we sort of gave that out. We said, initially, our first release was 25 per cent. What we were trying to say by naming that is, yeah, 75 per cent of the game is missing -- it's like giving you Call of Duty without guns. It is fundamentally going to be on the boring side.

"We said, initially, our first release was 25 per cent. What we were trying to say by naming that is, yeah, 75 per cent of the game is missing -- it's like giving you Call of Duty without guns."

Peter Molyneux

You say that it's like giving people Call of Duty without guns, which is obviously a crazy thing to do -- but you've done just that. I know it's early access, and that's a great thing for developers, but do you not worry that people's perception of Godus has been tainted by that? No matter how many warnings you put out there, a lot of people did play it, maybe for 10 hours, and in their mind it's now established as a boring game.

Well, firstly they played it for 10 hours, and that's quite a long time. Secondly, we needed those people. We needed to look at the way they played, to make the game not boring. Remember, they put down £14, and that gave them a pass to the entire life of Godus. Because the game changed so radically from the first release, from the early access in October to now, hopefully they'll see that they're on a journey of development, and this is what it's like to develop a game. When you develop a game, whether it be a role-playing game or an RTS or a God game, there's a terrible thing that often publishers and the team itself say, well the game's not fun. You have to discover the core of what the game is, and you have to amplify that. Maybe people won't stick with it, but this is the democratic world of development that we're in now.

We could have shut our doors and gone into our ivory tower and not released anything. We could have actually gone and got a publishing contract and kept a secret and come to GDC and release the game in a shock and awe campaign, but we chose to do this slightly crazy approach, which was to involve the community in the development side. The risks are people do say it's boring, or it's tedious or it's buggy or my wrist hurts from clicking too much. We can choose to say that's tough, do more wrist exercises, but instead we chose to go back to the drawing board, re-define it and look at how people approach the game and what they did.

That's why I said it's learn, fail and learn. One of the most useful things we found is that people found it boring. That's incredibly useful, because you can do something about that. That's why we introduced this concept of voyages, that you can send your little people on voyages. We always knew that the biggest motivator of Godus was the thing that we couldn't introduce until everything was set, which was this hub-world connecting people together. I'm not saying it's Call of Duty without guns, but it's a huge piece of the puzzle. Is it a risk that people like yourself say I know what Godus is, it's just a boring game? Yes it is a risk, but it's a risk worth taking, because the rewards from taking that risk is refining a game that you truly think will be great. It's great not because you think it's great, but because you've learnt from what's gone wrong.

What we're really trying to do, is we're really trying to define an experience on here that feels like nothing before. The fact that sculpting on this feels delicious and delightful -- it's a Zen experience that's designed not to put you on the edge of your seat, but just for you to play with. This is also part of the problem -- when you do a game, a game can often be defined as exciting. But I love the idea that I could play with this, or I could go off and I can do the exciting stuff and go off on voyages. It is a different experience.

Returning to the analytics, and letting people shape the development. Someone like yourself, you made your name with a singular vision like Populous. Is it not a problem having this democratic development? The best creative things tend to come from people who don't really give too much of a toss what others think and just do what they want to do. You see it still in Lucas Pope's Papers, Please, or in Fez -- but does that creative spark not get diluted when you get too many people involved?

That's where being a designer nowadays is different. I think part of my mind is I'm the person who comes up with the ideas, and the crazy idea of connecting people that seems like an impossible idea. And the other part is being a curator -- my job now, and it's exactly what I realised in October, is that we weren't developing a game any more. We were reacting to what people were doing and giving them what they want. That doesn't make a game better, it was just making the game different. Part of my creative mind is to look at the numbers, look at the way that people play and look at the feedback and what people want and what they need and what motivates them, and to cherry pick those things. And to say no as many times as I say yes -- to say no, I don't think that that's right, even though a thousand of you want this, I'm going to say no. That's my responsibility, to look at those things and bring it all together in one place. Let's not forget that what we're trying to do is reinvent a genre that's died. To do that, sometimes you need feedback from people, we need input, and sometimes we say no. The spirit of what we're making, and the big idea, is to make a game that anyone can play. That core gamers and casual gamers can come together and experience. And that means listening to all that feedback and making tough choices.

I agree, I've gone into my ivory tower before and I've locked myself away and not listened to anyone else. Maybe the dog in Fable, that was a feature that was like that. The development team on Fable 2 said we don't want a f**king dog, we want a dragon, but I said no, and I was universally hated in the studio for a while. Maybe that, for some things, that's the right thing to do. Just to say no, it's my vision. But nowadays, especially when you're making so big and so multi-platform that engages such a big audience that's been abused on a daily basis, you need to take input and it's your job to sort through that input.

You're not alone in going back to a genre that made your name -- Braben's gone back to Elite, Tim Schafer went back to point and click adventures with Broken Age. Is nostalgia getting in the way -- did these genres die for a reason?

Yes, in a way. If it was purely nostalgia that drove me -- this idea of reinventing the God game forced me to leave Microsoft, and the comfort and security that Microsoft represented. I had to spend many long evenings convincing my wife that this was a sensible idea, and not a mid-life crisis from someone who wanted the old days back. But the reason that God games died, in my opinion, is because consoles came along and there was no space for God games with a controller. That was the problem. Controllers are just horrible devices for open worlds for you to touch. As soon as they came along and dominated the scene, genres like the RTS and God games withered. But then along came the iPhone, and the resurgence of PCs, and that touch is the perfect device. It's not nostalgia -- we've got these two amazing things happening at the same time. Well, three.

The first thing is touch. Games that are invented for touch, and not adapted for touch but really invented, and there are some really great examples of that. The word I use is delicious, it's delightful, it feels like playing with clay or putty. That's the first thing. The second thing is we can really connect millions of people together in one experience. We tried that with Curiosity, and amazing and incredible things happened. Some were telling stories on the side of the cube, sometimes people were just tapping away without there being bullying or any of the caustic stuff. The third amazing thing is we're creating millions of new gamers a year, but the only things they have are these very caustic free-to-play models that are abusing them.

I want those gamers -- we all want those gamers. This industry has dreamt of being a dominant entertainment industry for decades, and we come up with these ridiculous statistics -- we're bigger than the music industry, we're bigger than movies. That's a load of crap. Sure enough we've got more money in the bank, but we're not bigger than them. We have a chance of doing that now -- but if we treat those people with disrespect... The ridiculous thing is there are people designing games around less than five per cent of the audience, and monetizing them so harshly and cruelly that we're burning through those people.

The free-to-play issue must be one close to your heart right now given what happened to Dungeon Keeper.

It didn't surprise me. The frustration wasn't the fact they did it, but the fact that it was so easy to fix, and they haven't fixed it. If you look where it is in the top grossing, it's there -- it's working. Someone going into EA and saying this is not right, it's a short-term approach to what could be an incredible place, that's what should happen. You can't go to people and say stop making millions of dollars and be good. That's what capitalism is all about.

So the cost is the terrible perception of games that comes from it.

Fundamentally, the big thing that no-one's realizing is that the digital relationship that people have with all forms of entertainment is changing radically, and places like the music industry are starting to get it right. They're not trying to stop people pirating now -- they're celebrating it with Spotify, you can download everything.

But isn't that industry screwed in terms of how artists...

No, they're starting to make money out of Spotify. Consumers are now starting to download -- they're reinventing it with Vevo, they're reinventing the way that they have the relationship with customers. They want a music video, and they're willing to pay for a music video. And rather than saying the only way people are going to consume our material is paying for it up-front, they're adapting to what the world is. The world's a changing place, and we in this industry cannot ignore it. We can't say that paying for something up-front is the only way to consume something. That's a short-term way of thinking about it. Fundamentally, being able to play and tempting people to spend money, in the same way that a supermarket tempts you to buy more than the cigarettes you came in to buy, that's really the art that we need to focus on. If we get it right, then people will not do the very thing we're doing with free-to-play right now, and saying I'm not going to spend any money, and spending money is cheating. That's obviously destructive.

"In the same way that a supermarket tempts you to buy more than the cigarettes you came in to buy, that's really the art that we need to focus on."

Peter Molyneux

How long will it take until it's not a dirty word, free-to-play?

I think there are two or three great titles that will come and prove that it can be...

They already exist, games like Dota and League of Legends.

There are already examples, but at the moment... Candy Crush I'm a huge fan of, but the amount of money they charge for things is unbelievable. They're not giving value. You buy the lollipop thing, it's like £5, and it lasts about a minute. It's unbelievable. A lot of those mechanics in those games are monetizing of addiction. And if you monetize addiction, that's like monetizing drugs. Addictive drugs, cigarettes for example, that's a great way of making money, for sure. But are they something that's going to grow? I think it's something that's constrained.

You're making a free-to-play game...

Well, no -- we're making a game which you can download for free. Let's leave it at that.

Does the business model encroach in the design process at all?

Yes, it has to.

Does that not become a problem -- as soon as the business model becomes the design, that's a problem?

No, because the biggest responsibility of a designer, surely, is to think about the money side. What I think about, what I want Godus to be is like a hobby. If we make it like a hobby... I love my hobby, my hobby's cooking and I love buying crazy, ridiculous gadgets for my kitchen that I hardly ever use. I love buying an incredibly sharp knife with which I end up in casualty 15 minutes after getting it. I love that. If I can get players of Godus into that mindset, that's a healthy place to be. Hobbies are a great thing, whether it's gardening or cooking or stamp-collecting or gaming. After all, the ridiculous thing about all this is the price of triple-A games! $60, for Christ's sake. That's an impossible amount of money. You compare that to films, TV, to any other medium, it's so over-priced.

We are going to end up continuing to pull out huge wads of money from the enthusiast audience, which is about 20 million people -- but that's not getting any bigger.

Here's the thing. I believe in what I'm doing. I believe so much. And people say Godus is boring -- I know they think that, and I'd be an idiot not to know that. What Godus is, and what it will become is yet to be written. But those people who've said it is boring -- they're part of that story.