Pentiment review: a wonderful tapestry of historical intrigue, and a welcome treat for Game Pass users

Nobody expects a lavish ink commission.

The Cadfael game is finally upon us. It raised a sea of eyebrows upon its unveiling during this year’s joint Microsoft/Bethesda not-E3 presentation in June, despite being a sort of weird, cartoonish (emphasis on ‘ish’) ‘medieval whodunnit’. Sandwiched between the likes of RedFall and Starfield, you wouldn’t expect it to cause much excitement. And yet, for many of us watching, it struck a lutey chord as one of the most promising looking titles on the entire Xbox slate, and a perfect example of Game Pass’ appeal: something that looks interesting, but is potentially too weird and experimental a proposition to risk real money for.

I’m delighted to report, however, that its promise has been delivered upon and then some. It easily justifies its price of entry, whether you get it as part of a sub or pay the frankly too modest £14.99 they’re asking for it on the store. This is despite the fact that it’s a huge narrowing of scope for Josh Sawyer, the director of such beloved and vast role-playing games as Fallout: New Vegas and Pillars of Eternity. Unlike his previous works, Pentiment takes place entirely in one small Bavarian town over the course of a quarter-century.

Its cast is miniscule compared to those other games, as is its budget. Probably. I haven’t seen Obsidian’s books, but this was made by a core team of 13 and doesn’t have any voice acting. There are fewer buildings in it than there are in the starter town of Pillars of Eternity. I bet the entire game cost less than it took to get Matthew Perry to do a dozen lines for New Vegas. It might have even cost less than the lines he was doing during the fifth season of Friends.

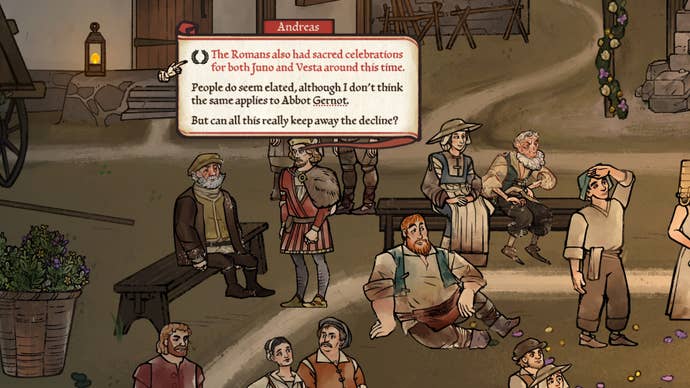

But these choices are not born of budgetary constraints. At least, it doesn’t feel like it. Everything about Pentiment feels like a deliberate, creative decision. The lack of voice acting is a clear example: the game simply wouldn’t work if you had to sit and listen to the dialogue being performed instead of reading each speech bubble as they magically write themselves in front of you, with ink blotting and the odd mistake that gets corrected in real-time. Some characters have scratchy, messy handwriting. Others have elaborate, gothic scripture. Others still have block-printed speech that appears instantly with a satisfying punch: this denotes that they are from the printmaker’s shop.

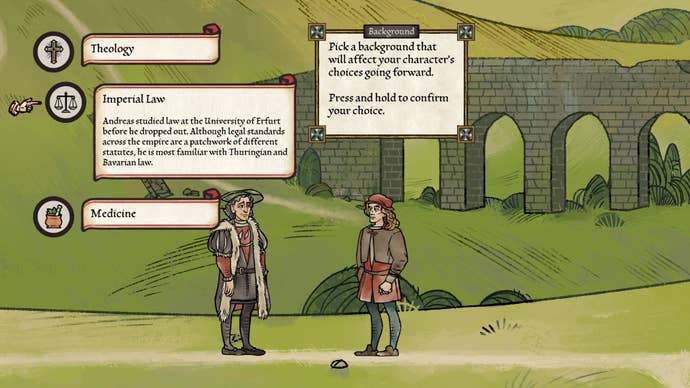

It’s a fascinating system which uses the medium of typeface in some wonderfully mechanical and inventive ways. Rather than simply a vessel for dialogue, the way the text is rendered on screen relates to how Andreas, the protagonist, an artist from Nuremberg finishing his gap year in the scriptorium of the local abbey, perceives an NPC’s status. Lowly peasants get the crappy chicken-scratch handwriting. Fellow artists get lavish block serif that’s carefully outlined and then shaded in, as a Benedictine monk would do when copying scripture.

It may sound like a trivial detail to fixate on, but it’s a conceit that is leveraged to brilliant effect as a giver of clues and revealer of twists. By having a much narrower scope than Obsidian’s other RPGs, which strive to depict entire cities, states, even continents, Pentiment can spend more of its time on making the small things matter.

This, of course, is vital to the ‘whodunnit’ side of things. During the game’s three acts you must gather clues and evidence in order to determine the most likely culprit for a heinous crime. Multiple lines of inquiry will open up, and you don’t have time to pursue them all to completion: it’s left up to you to decide which threads to pull. Attempting to turn every stone will result in a lot of cobwebs in the fact bank, and blank stares all round when presenting your findings. Saying the wrong thing can spook witnesses into withholding vital info – you must be careful, and considerate of a character’s manner, status, and personal history if you are to make them reveal damning secrets about themselves or others.

Some conversations will be closed off entirely if you don’t pass the requisite speech check, decided early in the game in the form of a casual conversation about your background, in which you get to decide Andreas’ passions, areas of study, languages read or spoken, and even what he did on his holidays. To be clear, this is an entirely speech-driven RPG: choices matter, but there’s no combat. This is post-Roman Bavaria, not Teutoburg Forest.

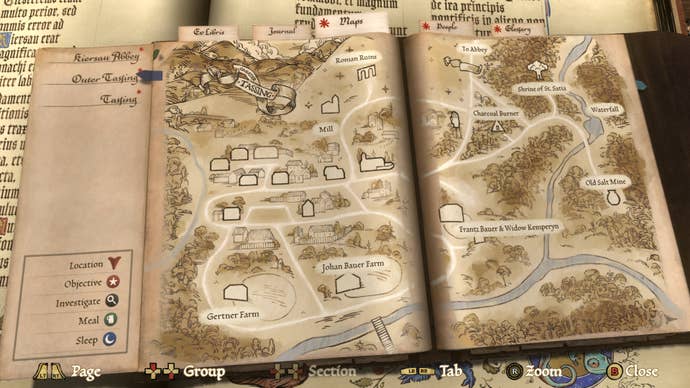

That’s not to say that bad things can’t happen to you. They can, and will. Perhaps the worst thing though is the nagging feeling that you wasted your time on a red herring and now have nothing conclusive to, er, conclude. Pentiment has a lot of replay value: no one playthrough can uncover all of Tassing’s grubby little secrets, reveal every location, or even feature every minigame. But I believe the game has more power as a one-shot. It takes 15-20 hours to finish (piddling by RPG standards, but mercifully plenty for those of us with grey temples and backache), and I think the choices I made during that time – some of which panned out, and some of which backfired spectacularly – make my Pentiment story something personal to reflect on. To go back in time with a head full of foreknowledge would seem to cheapen it, somehow, though this is not something I’ve ever felt about any other RPG.

Perhaps it’s because of how engaging the characters are. How important it feels to respect them. The abbey town of Tassing is fictional, but a composite of real places which would have seen similar hardships under the Holy Roman Empire: draconian taxes at the behest of local lords, rates of child mortality which we would consider unconscionable in the modern age, and the tempest of division unleashed by the protestant reformation. Though the characters are inventions of the writers, they give voice to the real people who lived through these unforgiving times. Real people who left very little of themselves behind, beyond some scant mentions in the accounts of the vastly privileged men who wrote the histories we rely on.

How a civilisation leaves its mark will shape its perception in the minds of those who come later. Much of the ancient writing we have from the Mesopotamians and Egyptians, for example, is concerned with mundane matters of payroll and taxation, and so we often think of these societies as being nations of accountants. We imagine the worlds of Classical Greece and Imperial Rome to be stoic, austere, rendered in plain white marble: but only because the gleefully garish paints and pigments that once adorned them have been sandblasted away by centuries of mild wear and tear.

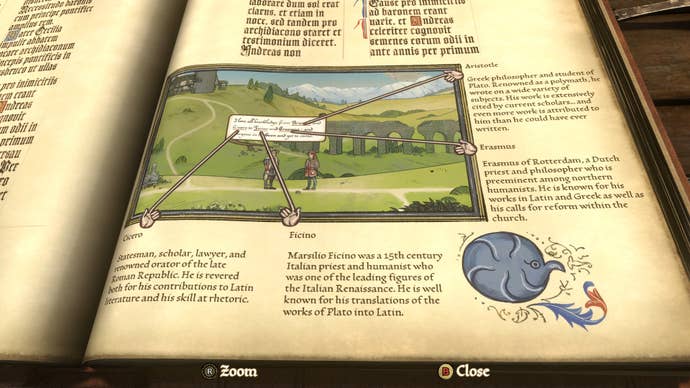

Pentiment’s visuals are a modern, interactive interpretation of the kinds of illustrations and frescos you would find on the book pages and plastered surfaces of 16th century Europe. At first glance, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the tone is something along the lines of a Monty Python interlude: unserious, farcical, perennially in danger of interruption by a giant foot. It requires a slight rewiring of your perception to fully click: bypassing the two centuries of penny dreadfuls, cheeky cartoons, the aforementioned 1970s sketch troupe, a hazy memory of that Procession to Calvary game you kept seeing pop-up a couple of years back. But though there are plenty of light-hearted moments, and a few brilliant sight gags here and there, the game tells a serious story about serious people living through serious times.

The town of Tassing, its people, and its surrounding environs, are drawn so vividly and expressively as to imbue them with life. Like every other aspect of the game, the basis of the visuals is painstaking research, and it shows. There’s something uncannily medieval about the cats (all of which you can pet, and there’s an achievement for it, as there should be). Of course, games are a visual medium, and so it seems trite and obvious to insist that Pentiment’s visuals are absolutely foundational to the experience, but without giving too much away, it matters here in ways that are pivotal, and deeply profound.

Building an entire video game out of 16th century painting and illustration – to painstakingly replicate its signatures and idiosyncrasies in glorious 4K, and rig it all to make it work in motion when it was never designed to move – must take so much effort and care. Much more than would be warranted if it were just a pretty neat idea, if the very soul of the thing wasn’t dependent on it. But it is a pretty damn neat idea all the same, and one wonders if it was the genesis of the entire project.

One section in particular concerns the painting of a mural (your character is an artist by trade, and this fact is not incidental) in order to depict the town’s history. It’s one of the most compelling sub-plots in the game, even though it’s one of the few things that don’t revolve around a murder. It requires you to research the town’s origins as a pagan settlement, through to a thriving Roman city, into the post-Roman period and beyond.

You rummage through broken pottery, decipher latin graffiti, and seek out the town’s elders to hear their folk tales. It’s quite moving, particularly if you’ve reached that sort of age where you regret not asking your own elders about the past while you still had the chance. Though it’s an invented history dreamed up by the writers, it is characteristic of the real story of Western Europe, and is once again a persuasive example of the power that interactive fiction has to breathe life into ages long past.

Having the game occur in Tassing at various points over a 25 year period brings with it the gift of that irresistible sense of continuity you get from something like Kamurocho in the Yakuza series, or the glimpses of repeat locations you get in Dragon Age. Tassing’s landscape changes dramatically over the course of the game, as the town expands, as the role of the local abbey changes against the backdrop of the reformation. Seeing characters who were toddlers in the first act grow into adults by the third is a nice tough, and in some cases, your earlier interactions with them can have surprising, lingering effects on their personalities.

That said, if Pentiment has any downsides, aside from the fact that it requires a lot of reading (so bear that in mind if that’s a dealbreaker for you), it’s that this is a Choices Matter game in which your choices only seem to matter superficially. Yes, selecting character backstory ‘A’ might cause cagey NPC ‘Q’ to unwittingly reveal clue ‘Z’, so your choices do have some visible sway during key moments, but it’s pretty obvious that the broad strokes of the story remain fixed for everyone. I mean, that’s fine: the vast majority of ‘choice & consequence’ games are elaborate illusions on the ‘consequence’ front, and it’s not for us to condemn a magician if he doesn’t actually saw his assistant’s legs off. But, and it’s impossible to be anything other than blunt about this: you don’t actually solve any murders.

Don’t get me wrong: you certainly find clues, construct motives, and finger suspects (matron), but it’s left quite open as to whether or not you’ve condemned the right person. If you were actually expecting a Cadfael game, something akin to Frogwares’ Sherlock Holmes series, you might come away feeling unsatisfied. But this, again, comes across as quite deliberate. Pentiment goes to great pains to remind you that history is inherently unknowable. We can see from the footprint where the owner of the boot might have been headed, but we can’t know if they were wearing a hat. Or if they bludgeoned anyone to death when they got there.

What it boils down to is that Pentiment isn’t really about solving crime. Sure, ‘medieval whodunnit’ works as a pithy descriptor (even though the less snappy 'early-modern whodunnit' would be more accurate, don't tell the mods) but it doesn’t hold up much beyond the first act. It's more about art as living history: how stories passed down through spoken tradition, the written word, or the painter’s brush, are a way for our ancestors to speak to us across the gulf of time.

The names, faces, joys, and sorrows of long dead individuals may now be lost in the fog, but we can get a fumbled sense of the world as they experienced it from the clues they left for us, and indeed, through new works that refresh and reinterpret their stories for generations hence.

Pentiment is about that phenomenon, and also a manifestation of it. It's one of the most engaging and accessible works of living history ever commissioned, and the fact that it exists at all - let alone as a major platform holder's first-party RPG heading into the Christmas season - is a miracle worthy of the saints.

Play this game.

Pentiment is available from November 15th on Game Pass, Xbox Series X/S, and PC via the Microsoft Store or Steam.