Outer Wilds' solar system only highlights the shallowness of No Man's Sky's infinite universe

What is it that makes the open world genre appealing?

I would argue it’s this: possibility. Hence the familiar refrain of “you can go there” that accompanies open world preview trailers or screenshots showing us distant mountain ranges - the promise that you, and perhaps even the developers themselves, never know exactly what you might find when you venture out. The innate appeal of being uncertain about what lies beyond the horizon is what these games are predicated on.

No Man’s Sky was supposed to be the ultimate expression of possibility. It’s “you can go there” promise beat every other pitch that came before it, blowing our collective minds with its unfathomable scale. This was a de facto infinite universe, the logical endpoint of an industry bragging about how sequels had maps five times the size of their predecessors, or offered however many hundreds of hours of gameplay. This was, for some, the realisation of the dream of what video games could be. It turned out that what video games could be was really, really big - and a bit boring.

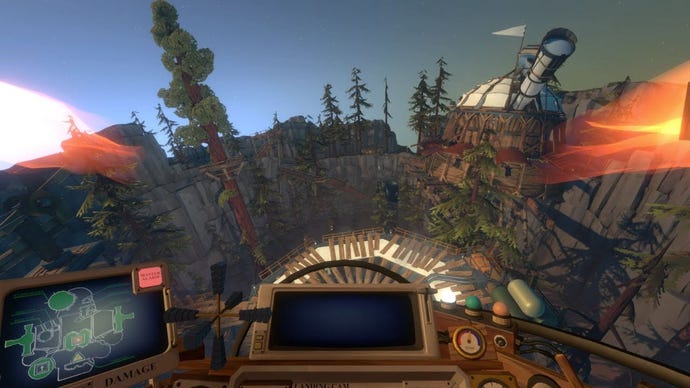

Here we come to Outer Wilds. The game shares some superficial similarities with No Man’s Sky – both give you a spaceship, let you launch yourself into the great void, and encourage you to explore the planets you find there. In Outer Wilds, however, you are confined to a handful of planets in one solar system. That still sounds like a lot, but the game is tiny in comparison to many of its open world contemporaries.

Within the logic of a genre that has an uneven focus on the frontier of scale as //the// means through which to evoke an ever greater sense of possibility, Outer Wilds bounded nature should mean it cannot compete with No Man’s Sky when it comes to the core of what makes open worlds compelling. Yet, the opposite is true. A large scale and the invocation of a sense of possibility are not intrinsically linked, it would seem. Our thinking around how open worlds work requires some tweaking.

Our starting point should be to remember that scale works in two directions. As well as broadening out, we can zero in. Detail and intricacy are just as effective a means of offering us more to explore as increasing the volume of the space we can play in. Think, for example, of the way you navigate the Dishonored series’ semi-open world levels. Multiple routes dovetail with an interlocking web of systems and strategies to create a latticework of potentialities in a small space. Pay attention to the details – a document, a line of dialogue – and new potentials are yielded which, significantly, also hints at the existence of undiscovered secrets they may, or may not, exist elsewhere. This use of intricacy in architecture, a complex interaction of systems, and an awareness of the power of contingency, increases the sense of what is possible in those games’ spaces in a way that makes them feel far more open than other titles 100 times their size.

We can apply this lens to Outer Wilds and No Man’s Sky. Outer Wilds’ planets may not be big, but they are intricate. They require different strategies that must be learned through active experimentation, accident, and the acquisition of knowledge to navigate. They play by different rules: you encounter anti-grav walls, collapsing planets, teleportation devices, and even quantum spaces that require you to jettison your commitment to basic laws of physics and rethink your assumptions about how to explore physical space. The variety and imagination you encounter in Outer Wilds’ spectacular spaces ties in beautifully with the clues you discover as you explore the solar system that provide hints about about locations and the rules that determine how you can access and navigate them. Because the discoveries you’ve already made have been so wonderfully surprising, these vague teases excite the explorer within you, keeping you eager to find out what a game that repeatedly upends your expectations might have in store for you next. Like Dishonored, its relatively small size does not stop it from feeling packed with possibility.

Compare this to No Man’s Sky. Technically speaking, the possibilities for discovery outweigh anything any other game can offer. Yet, this promise feels empty. No Man’s Sky’s procedurally generated planets are different, but they do not force you to change your approach to them to the degree that Outer Wilds does, nor are they are designed around an idea or theme. The planets in No Man’s Sky are bound by the same laws and are, therefore, necessarily a variation on a template. A different version of the same place, over and over and over. What you do to get to a new planet and what you do once you arrive never changes in any fundamental way. You fly, you land, you collect resources, you move on. The loop is always the same. You’re not asked to repeatedly learn new rules and strategies. Instead, you traverse space more efficiently by making numbers go up via upgrades to your ship and equipment. This means that it doesn’t take long with No Man’s Sky for you to feel like you know precisely what is possible in its infinite universe. It might technically be true that you never know what you might find next, but, in a sense, you kind of do.

Outer Wilds not only encourages us to think of scale and its value in different ways, it reminds us that space is not the only vector we can explore. The planets in the game’s solar system change over the course of a 22 minute cycle that is reset by the explosion of the sun at the centre of its system. This means that you explore these planets in time as well as space, gradually building a picture of how shifting landscapes could offer you access to new areas, or perhaps being treated to a delightful surprise as you just happen to find yourself in the right place at the right time – I just happened to be gazing at a location I’d been puzzling about how to access for some time before serendipity presented me with the solution by virtue of me standing there at the right moment.

By forcing us to return to locations at different times over a period where we are also slowly acquiring new knowledge, Outer Wilds achieves something No Man’s Sky can’t. It doesn’t need an automated production line of procedurally generated content that delivers the “new” by always pushing back the horizon. It delivers it by allowing us to see the same places with a new perspective – an entrance that could only reveal itself at a particular moment, or that could only be accessed after learning a crucial secret elsewhere. Each place is a mystery that changes before us as we unpick it, that reminds us that every other location we’re going to visit across this solar system won’t be understood until we’ve reevaluated it multiple times. This too, is a device to make it feel like Outer Worlds is full of possibility.

The argument here is not that making games big is necessarily bad. The point is that it’s not necessarily good, either, and certainly shouldn’t be something open world games are preoccupied with. It’s worth remembering that Shenmue, one of the most influential titles in the nascent days of the genre, was intensely focused on detail – letting you rifle through drawers, pick up objects and turn them in your hands. It experimented with time through its revolutionary day/night cycle where certain events would only happen at certain times. It was interested in the idea of NPC agency, expressed in a limited way through NPCs following their own routines. Granted, it didn’t always discover anything interesting in these avenues – waiting for a bus to turn up is not, it turns out, very much fun – but all these avenues were explored as a means of increasing our sense of what was possible in its virtual world, alongside the not insignificant size of its map.

It would be grossly unfair to suggest that open world games haven’t done anything interesting since Shenmue, nor that there are no games that have explored some of the ideas that game pioneered in valuable ways – Gone Home found a way to make sifting through cabinets compelling, Shadow of Mordor is one of the few games to place significant focus on NPC agency. Nevertheless, the general trend has been to obsess over size. You’ve heard it in the marketing. You can imagine what would happen if Rockstar had announced that Red Dead Redemption 2 would be smaller than Red Dead Redemption. Scale has dominated our concept of what is important in open world design, giving us the false notion that possibility always lies on the horizon. Outer Wilds is a welcome and refreshing antidote to that affliction.