One Collector's Quest to Find and Preserve the Rarest Retro Nintendo Artifacts

Nintendo Power mainly existed to sell games to kids, but to collector Stephan Reese, it represents something more.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

If the video game community is a bustling, well-wired city now, it was a ramshackle settlement in the early years of the NES. Lacking access to the wikis, websites, and social media connections we take for granted these days, kids huddled on their respective school playgrounds to trade game tips and information like barterers swapping foodstuffs. It's cliché now, but getting bad information from someone whose "uncle" worked for Nintendo was as '80s as Teddy Ruxpin and neon shoelaces.

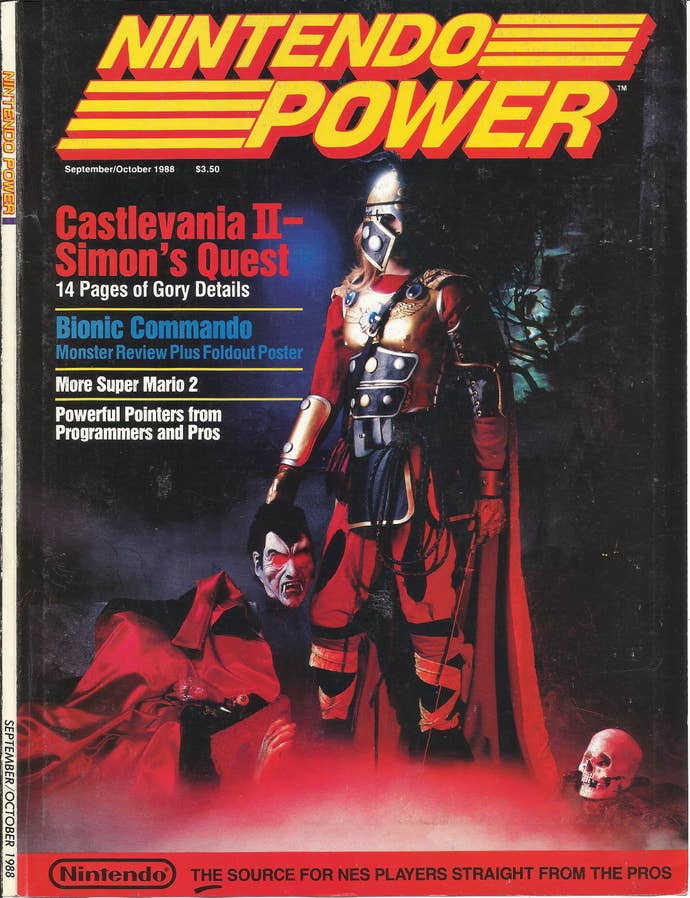

In 1987, then-President of Nintendo of America, Minoru Arakawa, realized kids weren't just starving for more games; they were famished for information about games. Inspired by youth-oriented magazines in Japan like Shonen Jump, he conceived Nintendo Power, a bi-monthly magazine that dished out information about upcoming games. It also published lengthy game walkthroughs, reviews, cheats, and tips.

Nintendo Power was put together with care and pride, but it's a key example of how problematic '80s nostalgia is. When President Ronald Reagan allowed children's television to air cartoons based around toys and games, we formed a deep, lasting love for properties like Transformers and He-Man. While not an exact analogy, Nintendo Power still existed to sell more games to an insatiable fanbase. Is nostalgia that's so deeply steeped in consumerism still valid?

It's a conundrum that's fun (and a little disturbing) to chew over with friends, or on a podcast. Everyone involved in the conversation has their own take, but when you interact with a hardcore Nintendo Power collector like Stephan Reese, it's impossible to deny the joy and comfort his hobby brings him. And the more you look at his collection, the more you realize the props and paraphernalia associated with games are worthy of preservation—even if they were sculpted to encourage kids to dish out for Mega Man 2.

Get the Power. Nintendo Power.

When Reese's late wife was diagnosed with breast cancer shortly after giving birth to their daughter, he learned that hunting down Nintendo Power art and rare memorabilia associated with the magazine helped "distract [him] a little" from the new, uncontrollable circumstances in his life.

"My wife's health continued to degrade. Her cancer was aggressively spreading, and my collecting habits were intrinsically linked to that. The sicker she got, the harder I went," Reese tells me over email. "[My] original Nintendo Power art collection was born out of that need to hunt things that were un-huntable."

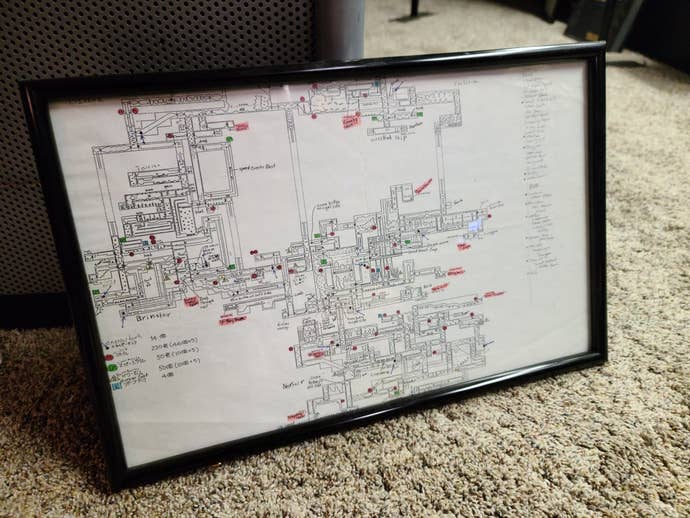

Retro game collecting is a popular hobby, and it's not unusual for people to collect Nintendo Power and other now-defunct gaming magazines. But Reese doesn't simply bid for old magazines and file them away when they arrive at his house. He collects the building blocks of Nintendo Power; one-of-a-kind items that never saw mass production. Cover art. Props for photo shoots. Even the binders Nintendo's 1-900 phone counselors used to guide kids through tough games, including a "forbidden Metroid map" said councilors consulted to lead callers through the warrens of Zebes.

"It's almost gotten to the point where, if there is more than one of something, I'm not all that interested," Reese says half-jokingly. "If it's for sale, I don't want it."

Reese isn't shy about sharing his collection on his Twitter feed, which garners more attention every day. The attention has led him to publish an FAQ about his collection. Reese is a bit private about himself and his connections: He usually doesn't disclose how and where he acquires his memorabilia, as he understandably doesn't want other collectors to muscle in on potential acquisitions.

Reese collected toys and games for about 30 years before he started his current Nintendo Power collection about five years ago, so he knows it pays to keep your mouth shut about your sources. He got deep enough into collecting retro games and consoles to complete several sets for North American systems, but he lost interest when he felt that collecting retro games was "expensive, not difficult."

"My tastes started to migrate," Reese says. "The rarer and more bizarre, the better."

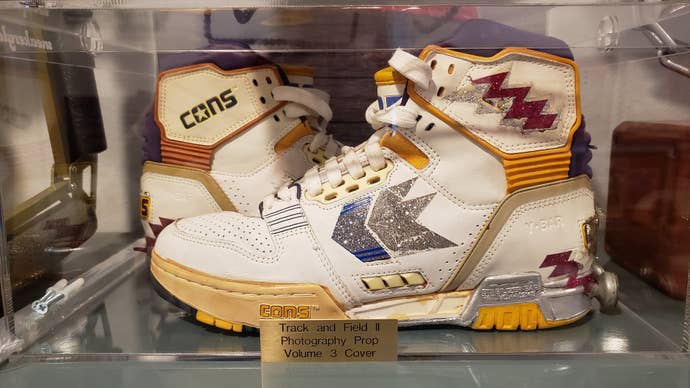

The acquisition that cemented his determination to collect everything weird and wonderful about Nintendo Power is comparatively mundane at first glance. It was a pair of shoes, but these high-tops have no equal in the world. They featured on the cover of Nintendo Power Issue 3 (November/December 1988), where they became rocket shoes that announced the Track & Field 2 guide within.

"Who would even think to look for those?" Reese says. "I was at [Portland Retro Gaming Expo] 19 in the museum, staffing a display I had put together all about Nintendo Game Play Counselors. A dealer came in talking to [GameHistory.org founder] Frank Cifaldi about them.

"Frank points the gentleman at me, and we strike a deal. A couple weeks later they are at my house. I remember when I pulled them out of the box, the first words out of my mouth were, 'these shouldn't exist.' And I was hooked."

Model Examples from a Rare Collection

It's true Nintendo Power was born to serve as a Pied Piper that led kids to buy more games, but that doesn't subtract from the artistry that went into making each issue. Many of Nintendo Power's covers feature unique artwork that's beautiful (artwork that Reese snaps up whenever he can), and its earliest issues are well-known for using models like the aforementioned rocket shoes. (As well as Dracula's bloody, severed head on the controversial cover for the second issue.) Someone sculpted these models, positioned them, and photographed them. Someone touched them up before the issue was printed. As commercial as these early issues of Nintendo Power are, there's nothing cynical about the magazine. If video game preservation is important, it's also important to preserve the bits of culture that orbit around the pastime.

Preservation is one reason Reese went hard on collecting obscure scraps of the foundation Nintendo Power was built on, but he admits it's different from preserving games and consoles. There's an undeniable element of selfishness to his activities, which he refers to as more of a "guerilla operation" compared to the community collaboration that sparks to life whenever someone finds a rare game ROM.

"In digital preservation, the output of the work is an asset that is easily shared and distributed. The world 'owns' it, so the people involved all feel like they've gotten something out of it," he says. "While I can photograph and share data and histories about a physical item, that thing still sits in my physical collection, or in a museum. The community doesn't get that same ownership out of it. That can be a hard sell when you consider the high dollar value of some of these items."

That's the sticky part of tracking down physical objects that can't be copied and distributed. But the rewards are rich, both for Reese and the gaming community. Two of Reese's most valuable acquisitions are the models of Mega Man and his rival, Dr. Wily, that were photographed for the cover of Nintendo Power volume seven (July/August, 1989). Mega Man looks a little squat and strange—the modeler was clearly trying to emulate his pudgy anime character art—but the detail that went into Dr. Wily's model is remarkable. His ship is accented by a tangle of brass cogs and machinery, and his face is carved with wrinkles and furrows. His hair, mustache, and eyebrows are all made of wisps of fake fur.

There's some unavoidable selfishness in the act of claiming these models, but it's also important that they go to a good home. Whoever made the models of Dr. Wily and Mega Man was undoubtedly collecting a check at the time; they had no idea they'd become part of gaming history. If collectors don't rescue what they can when they can, they might be entombed forever at the bottom of some dusty storage closet.

Worse, they might wind up like Hoggle, the remarkable goblin Muppet who had a major role in 1986's Labyrinth. Poor Hoggle rotted away as "lost luggage" for 17 years until he was found by chance and restored. Who knows how many rare items related to video game pop culture are disintegrating into mold? Who knows how many lovingly crafted pieces like that Nintendo Power Dr. Wily have been carelessly discarded or destroyed?

"I totally get that people look at this and say all of this game history stuff is navel-gazing bullshit... an irrelevant, wasteful, trivial topic,” archivist Jason Scott, told Ars Technica in a 2015 interview, “[But] mankind is poorer when you don't know your history, all of your history, and the culture is poorer for it." That's true for the dwindling material side of video games as much as the burgeoning digital side.

Nostalgia Drives Us, For Better or Worse

Reese can't share his collection as easily as the internet can share a ROM, but he's not interested in keeping it all to himself. He was set to exhibit his findings this year at Portland Retro Gaming Expo, PAX, and the Game Developers Conference—but the spread of COVID-19 and the subsequent quarantine axed those plans.

Despite the setback, Reese hopes to bring his collection to future shows as soon as conventions re-open en masse. Currently, he's more interested in doing pop-up shows than putting roots down in a permanent museum display, especially since The Strong is already a comprehensive video game museum.

"Doing convention exhibits is perfect for me because there is no overhead for staff or a permanent location. I can just show up, show you some stuff for a weekend, and be on my way," he says. "I'll tour the collection till I can't anymore, and then give it all to [The Strong]."

Nurturing a life-long love for video games and Nintendo Power gives rise to complicated feelings about the pastime. Is it okay to feel warm childhood memories toward toys, shows, games, and magazines that were created strictly to make the cash register ring?

There are a couple of ways to justify this love. First, acknowledge we're all sequestered on a pale blue dot that's spinning in a silent void that stretches beyond human imagination. Using old Mario games to fill the emotional void left behind by an absentee father is comparatively small potatoes.

But there's a warm, light side to humanity that drives us to create, to care, and do our best despite the circumstances. Reese fell into collecting and preservation as a means of coping with personal issues. By doing so, he pulls back the curtain on the hard work, intricate detail, and pride that went into preparing magazines like Nintendo Power. Reese found a way to come to terms with his wife's sickness, and by extension we get to revisit our childhoods from a whole new angle. We can also be assured these unique models and artwork prints are being preserved and cared for, even while the current industry still treats games as disposable cash machines that should be snapped from existence once they've outlived their usefulness.

Do Dr. Wily's forehead wrinkles justify our nostalgia? It's a personal question, one that you'll hopefully be able to reflect on as Stephan Reese continues to collect Nintendo Power stuff.

"I hear stories all the time about how an artist trashed something because it was taking up too much space in a studio, or gave it away, or has no idea where it might be," Reese says. "That's why I hunt so hard now. I just assume in my head that every moment I'm not finding something, it's being thrown away."