Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection and the New Impermanence of Gaming

Farewell, vanishing video game experiences. We already miss the days of buy-once play-forever.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Like many of you, I grew up taking media permanence for granted. Music and movies came on delicate but enduring discs. Books were big ol' bricks made of paper. Video games shipped as thick, nigh-indestructible cartridges.

It wasn't like it is now, when seemingly every form of entertainment can be transmuted into digits and relayed by any number of means. You can simultaneously download torrents of video games, movies, TV shows, books, comics, music and more through the same pipeline and enjoy them on the same computer, phone, or tablet. Currently my Vita sports the entire Final Fantasy series through Final Fantasy X (Tactics inclusive), the entirety of Shin Megami Tensei: Persona, the Parasite Eve trilogy, and about a dozen other games, all on a single PlayStation Vita memory card, which isn't even as large as the nail of my smallest finger. That's kind of awesome – but at the same time, it comes hand in hand with the fleeting new reality of video games, a truth that's considerably less appealing for anyone who regards games as something that might actually be worth revisiting more than two weeks after their debut.

Video games have lost an essential element of cohesion. They're no longer complete works in and of themselves. I know I'm not the only one to lament this fact; plenty of gamers do. You can see it in the demands of those who hold the idea of physical media in high regard, who clamor for a retail release for games whenever possible. But I don't think digital distribution is the enemy. On the contrary, it gives us access to ultra-niche software that publishers wouldn't have taken a risk on when retail was their only option. We missed out on the final DS installment of Capcom's Ace Attorney series, and cult classic Umihara Kawase has never once made its way west. But right now, you can download Ace Attorney 5, and Sayonara Umihara Kawase will be arriving here in less than two weeks – and all because of the lowered barriers made possible by digital distribution.

So what if these games only exist on a memory card? All those Final Fantasies I've purchased via PlayStation Network are mine to enjoy for as long as I manage to hold onto my Vita. Even if they end up being inexplicably delisted, or Sony itself collapses into bankruptcy and shuts down all its online services, I'll still be able to enjoy the games... provided I don't lose my Vita, of course. But how is that different from any older game? I wouldn't be able to play my NES games anymore if I lost those, either.

No, simply possessing a game on some sort of physical media doesn't mean a thing when the content therein is dependent on external services. Both Simon Parkin and Anthony Agnello have recently explored the challenges that face game preservationists and archivists as the medium abandons media. What good does it do you to own a copy of a great game if the servers that provide add-on content have gone offline? Why bother keeping around a disc for an online arena shooter if it's tied to a proprietary service that someday will vanish. When Xbox Live stops supporting Xbox 360 games, you'd better have patched up that copy of Skyrim and snagged the DLC.

This is hardly news to anyone who's been paying attention over the past decade. Plenty of high-profile games have gone dark over the years – everything from Halo 2 to Metal Gear Online. You could argue that dealing with shutdowns is simply the risk you take when you commit to a multiplayer game... but is that a reasonable risk to have to take for games that don't have a multiplayer focus?

Nintendo's recent decision to shut down its Wi-Fi Connection service this coming May is the first time I've been forced to deal with this sort of obsolescence face-to-face. I tend to avoid multiplayer games, including the multiplayer modes of primarily single-player games, so the loss of online support has never directly affected me. Until now, I've been able to dodge the darkened server bullet. But not every DS game that made use of WFC did so for the sake of multiplayer. One of those, it just so happens, was the single game I played more of than any other on DS, and one I had hoped to revisit someday: Dragon Quest IX.

By the time I put my copy of DQIX down a few years ago, I had something like 160 hours invested in it. Maybe a whole two of those hours were spent in multiplayer mode, and that wasn't done through WFC – DQIX offered only local multiplayer. Nevertheless, even though it was a retail-only release, DQIX incorporated online components that require a publisher-supported infrastructure... and once WFC goes away, so do those elements. Specifically, it'll lose out on the brilliantly named DQVC shopping network.

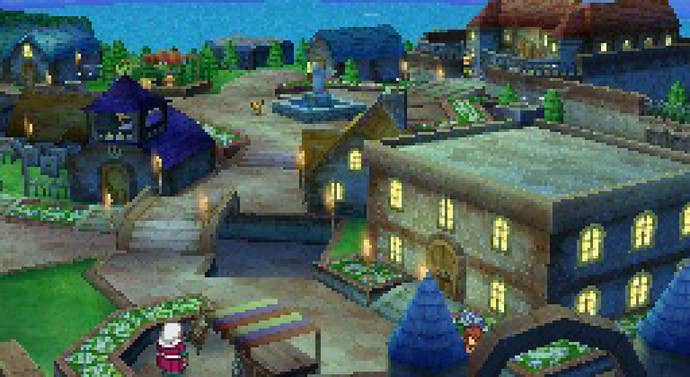

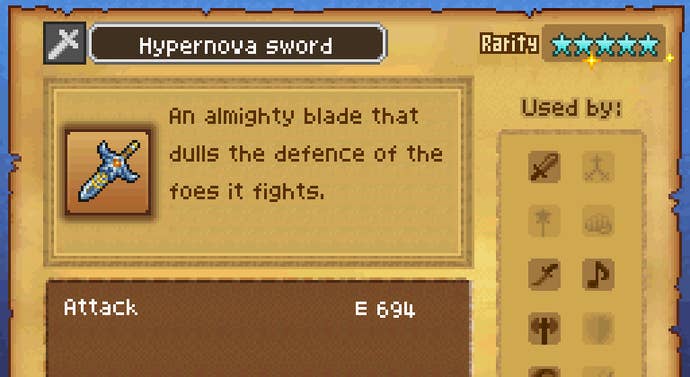

Every day, you could stop by Quester's Rest, the central pub that served as a nexus for so much of DQIX's content, and log onto the Internet to find hot deals on rare items. Unique items unavailable through any other means (like Santa hats and birthday cakes) would show up on DQVC. More importantly, though, rare high-level alchemy components – ingredients that would normally take hours to create through proper means – would appear at random on DQVC, allowing you to exchange a chunk of cash in order to save yourself a massive headache for creating the game's most advanced gear sets. Besides the daily stock refreshes, DQVC's overall theme would change from week to week as well, increasing your likelihood of tracking down certain items. For a serious DQIX player, the DQVC became an essential tool, especially for high-level play.

Now DQVC – along with so many other WFC-based features like Pokémon's Global Trade Station and Mario Kart's online racing – is going away forever, and when it disappears so will a key element of a game that otherwise had no need for the Internet. The game won't be unplayable after this, but it will absolutely be less complete — compromised.

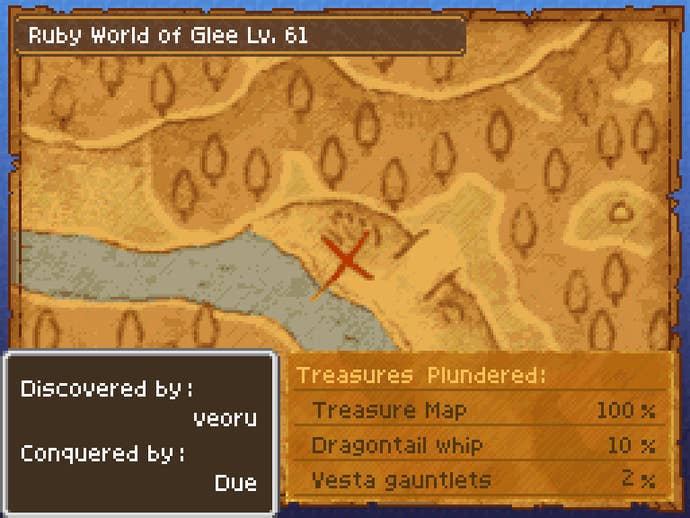

I guess it's no big deal in the grand scheme of things, but I find it disappointing on a personal level. It means that second copy of the game I picked up for a future playthrough will largely be wasted. It's bad enough that I'll never be able to have a truly satisfying replay of DQIX since Street Passing comprised so much of the experience; bringing other players' avatars into my Quester's Rest and gathering the treasure maps they brought along kept me entertained at several consecutive PAXes. I can't imagine ever having another opportunity to be in the same space as several hundred other people actively transmitting DQIX Street Passes (remember, in the olden days before 3DS, that wasn't a passive system-level feature), so I'll inevitably miss out on an interesting social element that added high-level perks to the game. And now, with the death of WFC, I'll be unable to access another advanced feature of DQIX.

Even without those components, DQIX remains a pretty great RPG. Nevertheless, when publishers kill off connectivity features, it chips away at the integrity of games like this. But why should they care? There's no business sense in supporting out-of-print games for obsolete systems; Dragon Quest IX isn't making any money for Nintendo or Square Enix at this point, so why worry about the long-term well-being of the game or its community? Sure, some of Nintendo's online-enabled first-party titles are still being sold at retail, such as Mario Kart Wii... but putting aside the fact that the only model of Wii console currently available in stores doesn't support online features to begin with, doesn't it seem awfully coincidental that the WFC shutdown happens just 10 days before Mario Kart 8's launch date?

I've always gravitated toward console and portable games, but as they begin to incorporate more features that could potentially vanish at any time, I increasingly find myself questioning the wisdom of not just giving up and migrating over to PC gaming like so many others I know. Not that Windows-based games are any less likely to see their online support up and vanish at a whim, but unlike consoles PC games don't operate in an entirely closed ecosystem. It's easier to fake a server for a PC game than for a Nintendo game. Sure, PCs have their closed ecosystems, too – Steam, for example, and all those awful publisher-specific services like Origin and uPlay – but the platform lends itself to hacking by its very nature. There's a pretty strong likelihood that when a publisher stops supporting a PC-based game or service that you'll be able to hop onto a torrent site and snag a patch to reenable things almost immediately.

Of course, you could argue that consumers have no right to do that, that buying software is merely purchasing a temporary license that leaves you at the tender mercies of a publisher's whims, that you have no personal rights once they yank support for the products you've paid for. But that's exactly the sort of miserable, consumer-unfriendly idiocy that drives many people to piracy in the first place.

Ultimately, much as I'd like to offer a constructive solution for the publisher-side decay of so many games, I don't have any answers. Do we get rid of consoles? Get rid of innovative online features? Stop buying games? It all seems so defeatist. But then again, the fact that I'll never again be able to experience one of my favorite games of the past five years in its entirety feels like a kind of defeat as well. I had a phenomenal time playing Dragon Quest IX, but I wish I'd made more effort to savor the experience. I had no idea it would turn out to be so ephemeral.