Nintendo PlayStation Grabbed Headlines, But Support for Preservation Remains "Dismal at Best"

We talk to game preservation experts about what's been preserved, what's been squirreled away, and what's already been lost.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

If you're a developer and you're reading this, stop and ask yourself: What have you already tossed out? Are you the type of person who keeps meticulous digital backups, or do you wipe old hard drives with glee? How many cardboard boxes of notes and other ephemera do you keep around? These are extremely basic questions of preservation, and yet a lot of developers may think of them as a distraction from the "real" work of making games.

Meanwhile, these simple elements of preservation tend to be overshadowed by the collection of flashier artifacts from throughout gaming history. Take the famous "Nintendo PlayStation" prototype console that was just sold at auction for $300,000: The unit itself marks a time just before Sony entered the home console market with its own system, and is fascinating for that reason alone. On the other hand, there's nothing terribly interesting about its design and function, or at least nothing that couldn't be reasonably guessed at from what we knew of the prototypes' existence.

The prototype is now owned by Greg McLemore, a collector who plans on lending the console to at least one museum, and who hopes to open a "permanent museum" of his own in the future. When Oculus founder Palmer Luckey revealed himself as one of the other six-figure bidders on the console a month ago, his claims of owning the world's "largest game console collection," and of working toward a "perfect VR" simulation to preserve the experience of physical games, were swiftly met with pushback and skepticism. Though Luckey says he understands game history and preservation is about more than the games themselves, his initial comments shed light on a core problem facing the field.

"The video game industry itself continues to lack a historical mandate," says Laine Nooney, an assistant professor of Media Industries at New York University who studies the history of personal computing and video games. The main focuses of Nooney's work are Sierra On-Line and its co-founder Roberta Williams. Nooney says that work has been aided more by communal efforts from Sierra fans to preserve the company's history than through the work of private collectors, or Sierra's own archives.

"For me, accessing private collections have been less important than the amazing work the broader Sierra fan community has done scanning company magazines, game boxes, and other kinds of ephemera, and putting it online, either at sites like MobyGames, on the Internet Archive, or even on some of the Sierra fansites," Nooney explains. "Certainly there are some private collectors who have items that I'll probably never access, but as a social and labor historian, I'm not trying to get my hands on sealed game boxes or one-of-a-kind products or prototypes. I'm interested in less obvious historical documents, like internal memos, organizational charts, business and operational documents, clippings books, internal newsletters, employee handbooks, and the like."

At GDC 2017, Nooney gave a talk called "Save Yourself: Game History is in Your Hands," where she compared Ken Williams' Sierra archive to that of a contemporary: Broderbund Software co-founder Doug Carlston. While the Willams' kept items that amount to "an archive of the company's image," Carlston filled boxes with those "less obvious historical documents," even going as far to hold on to notes that developers took at early industry conferences (both the Williams collection and the Carlston collection are held at The Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York).

In Nooney's view, the industry hasn't improved its practices since 2017. "While there might be individual actors or initiatives, there's been nothing operating at broad scale. I wish that could change, especially as we consider how new kinds of game production, distribution, and consumption are presenting whole new challenges for game preservation. Games that need constant online access, or are driven by microtransactions, don't have an obvious pathway to preserving 'the game' in the traditional sense."

We May Not Know What We've Really Missed Until It's Gone

The idea that we'll lose ways of experiencing old games, or that units like the Nintendo PlayStation will vanish, feeds into "a perennial crisis around the 'loss' of game history," that's created by games writers, Nooney argues. Whether an individual or organization sees bootable games as a primary concern, or just a small piece of the puzzle, in Nooney's view the work of history is an interpretive act and the lack of conversation about what else needs to be saved is of a higher concern.

"I often see the desire to 'save everything' as an extension of the toxic fantasy that technology can solve everything," says Nooney. "[T]here are so many other kinds of historical artifacts, both physical and digital, that are also worthy of our historical attention. The fact is games have probably been better preserved than any other segment of American software or hardware history. What aren't we even thinking is important enough to save? That's the story historians will be telling in 100 years."

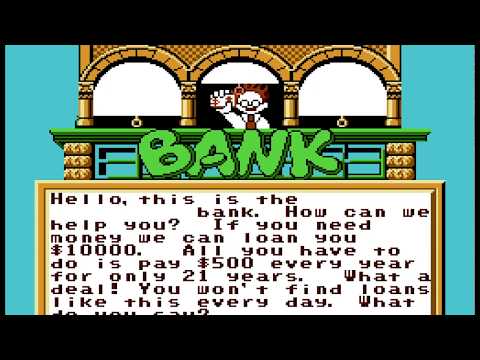

Through this lens, the idea that the Nintendo PlayStation in particular must not recede from the public's reach starts to look even more specious than it might have already, especially considering how extensively it's been documented and how ordinary its functions are. "It's a Super Nintendo," says Kelsey Lewin, co-director of the Video Game History Foundation. "Well, a Super Famicom, I should say. You put a Super Famicom game in there and boot up, say, Street Fighter, and then you can sit there and play Street Fighter, but on a very different looking Super Nintendo."

The unit also isn't one-of-a-kind; Sony and Nintendo made a lot of prototypes, though others haven't been available to the public. John Hardie, director of the National Videogame Museum in Frisco, Texas, says he's aware of "four of five different ones" out there.

Big auctions for sealed games and units like the Nintendo PlayStation grab people's attention—and spur games writers to capitalize on the spike in interest—but they can serve to distract from the work that needs doing today. It's in the less glamorous documentation, source code, and concept art that the real history can frequently be found.

"I think we're in the earliest days of preserving raw game data—I think that hasn't even started yet," says Frank Cifaldi, VGHF co-director. "By raw game data I don't mean the data that's on the disc, I mean what we're focused on long-term: the actual source material used to build the game. The source code, original art assets, things like that. To us, that's the equivalent of having the raw film reels from shooting film, which we do have a notion of in film archives. It would be the equivalent of the Library of Congress only having DVDs and not the nitrate film masters."

This is, in a historical sense, par for the course. Cifaldi cites a Film Foundation estimate that half of all films made before 1950 are gone.

"All media experience forms of loss," Nooney says. "All media struggle to 'save' themselves. History isn't intended to create a one-to-one representation of the world."

There's Been Little to No Industry Support for Many Efforts

"Anything you think is not worth something—historically, it is to us," says Hardie. Hardie and his fellow National Videogame Museum co-founders were collectors and archivists for years before founding the Frisco physical location in 2010. From his decades of experience working on collector's guides, putting on traveling exhibits, and now working on the museum, Hardie's also of the mind that companies still aren't on board with preserving their own history, or with supporting institutions that do it for the industry.

"We don't really know to what extent the archives are of many of these companies, because it's just not something they share information about," says Hardie. "I think some of them have learned that they need to preserve some kind of archive, but how many of them actually do? It's rough. I can tell you the support for us, as a non-profit institution doing preservation work, has been dismal at best. There's a few companies that have helped us and worked with us, but the big name companies... I think their mindset is just their IP."

In Sheffield, England, there's another National Videogame Museum, and two of its lead staff—Iain Simons, director of culture, and Dr. James Newman, head of collections—just founded a new initiative, the Videogame Heritage Society. The Videogame Heritage Society is a subject specialist network or SSN; it's Simons' and Newman's belief that collaboration both across different game history museums and with private collectors, regardless of industry support, will prove vital to better history keeping moving forward.

"Many of the most well-developed collections of hardware, software and ephemera are assembled by private collectors who possess extraordinarily deep knowledge about these objects and their histories," say Simons and Newman in a joint statement to USgamer. "One of the great challenges and opportunities of game preservation as we move forward is to find ways to connect experts together so we can all benefit from the shared knowledge and insight, and the resources and collections care facilities."

Simons and Newman say it's fair to characterize the industry as not having been "too concerned with preserving its own history," in part because it's young and still lacking in cultural confidence. "[T]he industry has spent a huge amount of time defending its own legitimacy. Perhaps it's time now to just start participating in contemporary culture and embracing that preserving and understanding the past of video games is essential to securing their future."

For the work of the British NVM and the Videogame Heritage Society, that means everything from paper conservation for design docs and player-made maps to data forensics, especially for depreciated formats.

"I think most people, really, when they think [about] video game preservation, even when it's coming from a good place, they don't really see past making the games work," Cifaldi says. Cifaldi and Lewin both raise the point that many well-meaning individuals essentially conflate the idea of knowing the industry's history with having playable versions of games, which is a problem they're not alone in seeing as essentially solved. "It's not disappearing and rotting at the same rate as what we're focused on," says Lewin.

"Bootable software certainly ties into preserving the history of video games, but to us it's kind of a small chunk of it, which maybe sounds counterintuitive," Cifaldi explains. "The games themselves, to me, if they have no context around them, then we haven't really saved their history. We've just saved, I don't know, their corpse."

Still, any longtime player can probably name a handful of instances where companies, collectors, and preservations have failed to save even that. "A great story is years ago, when Activision did one of the first game packs for the Atari 2600 games on Windows, they didn't even have the ROMs for the games," Hardie recalls. "We have tons and tons of stuff from the old days when we were using EPROMs and floppy disks. We're 30, 40 years in now, and recovering some of the data on that stuff has really been a challenge."

Committed to Doing What Ninten-Don't (Along With All the Others)

One way the VGHF contributes to video game history is by writing about its own processes, targeting readers beyond those who're actively involved in game history and preservation work. This month, historian David Craddock assembled a history of "Where in North Dakota is Carmen Sandiego?," the most obscure entry in Broderbund's edutainment series. In 2018, Cifaldi published a thorough breakdown of the creative, technical, and marketing contexts for the NES SimCity prototype that private collector and VGHF board member Steve Lin managed to secure.

With the Videogame Heritage Society SSN, Simons and Newman hope that it will embrace as broad a range of participants as possible. "If we want to account for the richness and diversity of gaming and reveal the distinctive local and regional histories, we need to ensure that we don't only focus on the already well-known, well-loved, popular or commercially successful systems, platforms and franchises, or the work of particular developers and studios," they say. "This is all important, of course, but for every NIntendo Famicom, there is an FM Towns Marty, or a Dragon 32, or a clone of a Game & Watch.

"Again, it's important that we connect collectors and collections partly so we can establish what is being done, what we already know, and where expertise and objects are held—but also so we can start to build a clearer picture of where the gaps are and which objects and stories are most vulnerable."

At the National Videogame Museum in Frisco, Hardie has established a series of exhibitions that rely primarily on the work of private collectors. "The first collection we did was a local gentleman who collected Alien stuff," Hardie recalls. "He had every video game to ever come out that had to do with the Alien franchise, in addition to some cool statues and stuff like that. [...] The museum will chip in stuff from our collection-perfect example, I would say 90% of the [current] Sega Channel exhibit belongs to this collector, but we had a prototype cartridge of one of the games, and a shirt he didn't have."

Whether or not the industry gets on board with better, more transparent preservation, and no matter if an SSN or another globe-spanning solution makes for stronger ties between private collectors and institutions, we should be thankful to today's curators, archivists, and historians for what we do have. As resource-strapped as a lot of the work has been, it's hard not to see the resilience behind it as a good sign for the future.

"[Atari] came to me and my partner Sean Kelly and asked us if we could dump ROMs and get them the actual data for their own 2600 games," Hardie recalls. "That's what we're here for. If they're not gonna do it, we are."

Hopefully, if the Nintendo PlayStation does end up in a museum opened by its new owner, it'll be one of many nodes in a growing, thriving network dedicated to preservation, accessibility, and insight. Maybe Nintendo and Sony could even get more involved with telling the unit's story—now that'd be something.

Photo credit: Jeremy Parish