Nintendo Gets Into the Game

Three decades ago, Nintendo parlayed a single arcade hit into a home gaming dynasty that remains strong to this day. Their secret? A strong belief in quality, the cutthroat pursuit of profit, and an occasional dash of humility.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

About 25 years ago, "Nintendo" replaced "Atari" as the default populist term for playing video games. Similar to how Texans always refer to soft drinks as "Coke," you can measure the cultural impact of a corporation or product by the way people use its name as shorthand for the concept it represents. Atari had a good run through the first half of the '80s, no doubt thanks in large part to to a string of TV commercials that ended with a vocoded voice singing, "Have you played Atari today?" But then the crash came and the Nintendo Entertainment System rose from Atari's ashes. Before long, Super Mario Bros. and Mega Man made their way into millions of households. And parents and grandparents began thinking of "playing video games" as "playing Nintendo."

In other words, Nintendo had truly arrived. But nothing about the company's rise to ubiquity was a given.

In 1983, Nintendo wasn't a particularly big player in the games industry. They'd certainly made a splash with 1981's Donkey Kong, perhaps the world's biggest arcade hit outside of Space Invaders and Pac-Man, as well as a juggernaut of merchandising. Yet while follow-up titles Popeye and Donkey Kong Jr. did reasonably well for themselves, neither had the impact of Kong. There was nothing about Nintendo that would have given anyone reason to believe that they'd become the de facto standard of home gaming. Any number of other publishers could theoretically have done just as well in the console market, such as Midway or Namco. In fact, one of Nintendo's competitors in the arcades, Sega, made a bid for television domination simultaneously with the Famicom.

Yet Nintendo had an advantage over other game publishers: Namely, video games weren't its primary business. The company had been around for nearly a century, producing playing cards, character merchandise, quirky toys. Its experience manufacturing and distributing toys gave it an "in" to gaming with a dedicated Pong clone system called the Color TV Game, followed by the ingenious Game & Watch series, which harnessed LCD pocket calculator technology for the sake of fun.

Another Nintendo advantage: Unlike many of its competitors, it handled its own arcade distribution internationally. Where Japanese competitors Sega, Konami, and Namco had forged deals with local distributors such as Bally-Midway, Nintendo's machines only bore a Nintendo logo. This had nearly been the company's undoing at the dawn of the '80s when its Space Invaders clone Radarscope failed to sell to American amusement vendors in the numbers they'd expected. But even that failure (mitigated at the last second by the hail Mary pass of converting Radarscope systems into the wildly popular Donkey Kong) contributed to Nintendo's collective wisdom.

By the time the company at last trained its sights on the home market in a serious way, it had decades of experience and wisdom to draw upon. One lesson in particular guided the Famicom's creation: Make it cheap, but don't compromise quality.

Razor and blade

Maximum content for minimum price had been a guiding philosophy at Nintendo for quite some time. It was a sort of mantra for designer Gumpei Yokoi, the inventor of Game & Watch; he saw great value in finding creative ways to get the most out of inexpensive materials and technology. And NCL president Hiroshi Yamauchi used this as the central philosophy for the Famicom's design: Offer gamers the most for their money. "Yamauchi's only real order to [Famicom hardware designer] Masayuki Uemura and team was to make the system as good as possible, for as cheap as possible," says former 1UP and GamePro editor Kevin Gifford.

Uemura managed to come up with an impressive machine for the time while wringing out every last penny (well, yen) of inefficiency. At the heart of the Famicom ran a variant on the MOS 6502 processor, a piece of technology that was nearly a decade old by 1983 and had been remarkably inexpensive even when it was new. The console's two controllers were hard-wired into the system to save the cost of a connector; the designers instead went with with a single extra controller port. Its top-loading cartridge design was both simple and durable, and its rugged case took up very little space compared to American systems. Its controllers featured only four buttons and a cross-shaped digital directional pad, a far simpler design than the stick-and-keypad designs offered with Intellivision and ColecoVision. The system didn't even have an expansion port; the eventual diskette-based add-on had to plug into the system through the cartridge slot.

Despite its stripped-down sensibility, the Famicom offered more power than any other console on the market. Unlike the competition, it could push dozens of four-color sprites at once and handle smooth scrolling. "The Famicom looked very next-gen compared to other Japanese consoles at the time," says Chrontendo creator Dr. Sparkle. In addition, the console also included some quirky extra features, like a microphone integrated into the first player's controller.

The Famicom debuted in Japan on July 15, 1983 for a price of ¥14,800 (loosely $150), making it far cheaper than personal computers and most competing consoles.

Quality, not quantity

Even then, Famicom's success wasn't a slam dunk.

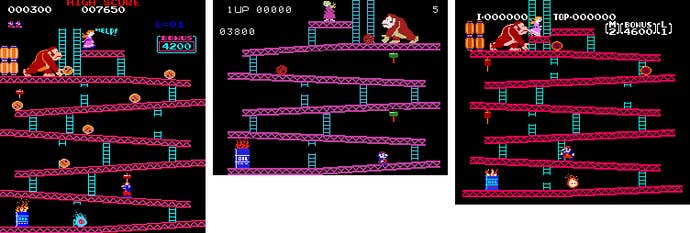

For starters, Nintendo launched the system with only three games: Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Popeye. By the end of 1983, Sega's SG-1000 (which launched the same day as Famicom) had nearly twice as many games available. Granted, Nintendo's three titles had the benefit of being popular, recognizable arcade hits. The home conversions weren't perfect, but they beat anything else on the home market. Still, the scarcity of content must have been noticeable.

But perhaps it didn't matter. As Dr. Sparkle notes, "At the time the Famicom debuted, all console releases had soft launches... new games trickled out a few at a time as the install base gradually increased. Atari was in a similar situation when it released the 2600; it took a couple years for the system to be considered to be a huge success.

"Third party software was not considered necessary or even desirable at the time. Atari tried to sue third-party publishers, and Sega had virtually none. Video game fans did not have the same set of expectations, nor feelings of entitlement that they have today."

On the other hand, the Famicom's innate advantages over the competition weren't necessarily visible at the outset. "Early Famicom releases were fairly simplistic, and not really all that different from the types of games on other platforms at the time," says Hardcore Gaming 101 editor Kurt Kalata. "If you were to compare the Famicom versions of Popeye and Donkey Kong to their earlier Colecovision counterparts, the Famicom versions are better, but the gap in quality is not substantial.

"It wasn't until Super Mario Bros. was released in 1985 that it became clear how much more powerful the Famicom was. The music was catchy, the game was fast, and the scrolling was smooth. The release of the Famicom Disk System in 1986 allowed games to save data and record progress. This opened the door for more long-form games like The Legend of Zelda and Metroid, thereby heavily increasing the sophistication of the machine, which had previously only been seen on home computers."

Until then, though, the race could have potentially gone either way. Nintendo made a huge investment in marketing the system ("From what I understand, Nintendo kicked off a huge advertising campaign for the Famicom’s release," says Dr. Sparkle), but ads can only do so much. Surprisingly, many people credit Nintendo's eventual triumph to a critical flaw in the Famicom hardware.

Bringing Achilles to heel

The earliest Famicom systems suffered from two issues, in fact. Cosmetically, its controllers initially featured square buttons which had a reputation for sticking after repeated use. Inside the machine, however, a more crucial issue with the processor caused the machine to crash or freeze under certain conditions. Nintendo elected to recall affected machines, a move that cost them dearly, but which also served as great public relations.

"Yokoi suggested that the company could replace units when customers complained," David Sheff recounts in his book Game Over. "Hiroshi Imanishi, who was working on the marketing of the new machine, said that the problem could be more severe than whatever number of units had the defective chips; it could cost more than the hundreds of thousands, or perhaps millions, it would cost to fix or replace machines.... A delay would allow competitors to swoop in and capture the customers that Nintendo had worked so hard, and spent so much money, to win.

"Yamauchi listened to the opinions of his staff but ignored them. 'Recall them all,' he said."

The Famicom recall cost Nintendo dearly in the short term, but by many accounts engendered a sense of trust among consumers rather than suspicion. Because Nintendo preemptively and electively recalled the systems rather than being forced to do so under scrutiny, they presented themselves as good corporate citizens. Between this responsible approach to business and the system's slim but strong software lineup -- Nintendo published several original titles alongside several more arcade ports over the console's first year of life -- the Famicom eventually edged out its rivals.

Party of three

What really cemented the system's popularity, however, was Nintendo's decision to embrace third parties. About a year after the Famicom's debut, third party releases -- primarily from Hudson, Namco, and Tecmo -- began appearing in stores, greatly increasing the depth of the console's library. The system exploded in popularity, selling millions of units in its first couple of years, while only a few dozen games were on the market (the system's Japanese library alone would go on to top 1400 official releases by 1994). Not surprisingly, those few dozen games sold exceedingly well.

"A heavy aura of nostalgia surrounds them to this day," Dr. Sparkle says of Nintendo's earliest Famicom releases. "Nintendo also released a port of Irem's Spartan X, known as Kung Fu Master in the U.S., which was not only one of the first side scrolling beat-em-ups, but also one biggest hits in the Famicom's early years. Hudson's Star Force was the first game in their annual Caravan gaming tournament, and kicked off the Star Solider series of shoot-em-ups. And Namco's Tower of Druaga was sort of a proto-Zelda dungeon crawler known for its tons of secrets and hidden items."

Indeed, a certain cult status has been built up around these early Famicom classics in Japan. While American gamers wouldn't think twice about Star Force or Tower of Druaga, our Japanese counterparts love them (or in some cases, such as Irem's port of Spelunker, love to hate them). Copies of Hudson's Nuts & Milk and Chack'n Pop line used game bins in Tokyo the way American pawn shops shudder beneath the collective weight of millions of Sega Genesis sports games.

The downside to the arrival of third parties was that Nintendo hadn't quite learned the lessons of Atari and didn't initially have much in the way of controls in place for its licensees. "In Japan, Nintendo did not even pretend to bestow Famicom games with a 'seal of quality,'" says Dr. Sparkle. "Publishers manufactured their own cartridges and could release just about anything for the system, no matter no cheaply made or buggy it was. Many companies with no video game experience began flooding the market with games created by anonymous contract developers. Scores of hastily produced licensed games hit the shelves, most of which were uninspired at best or unplayable at worst. Today we can get a certain amount of enjoyment from notoriously terrible games like Super Monkey Daibouken, but the kids who spent 5000 Yen on it 27 years ago were probably not very amused. The surprising thing about the Famicom library today is how much of it consisted of utter crap."

"After the [first] six licensees had begun selling games," writes Sheff, "Yamauchi realized that he had not only given away his ability to control the quality of the cartridges... but some potential profits as well, because he allowed the companies to manufacture their own games. Henceforth, Nintendo would be the sole manufacturer of games for the Famicom. The licensees would develop them and then place the order with Nintendo for a minimum of 10,000 cartridges. The terms were elegantly simple: Nintendo insisted on cash, in advance."

Nintendo's restrictions caused considerable friction with some early licensees, especially Namco, who resented being forced to change the terms of their Famicom business after playing a not-insignificant part in popularizing the machine. Things went more smoothly with licensing overseas, though; by the time the Famicom launched in the U.S. as the Nintendo Entertainment System, most licensees had come to accept Nintendo's demands and were only too happy to pay up front for the privilege of taking part in the Nintendo juggernaut.

From its humble roots, the Famicom survived strong for more than a decade, and the games that dominated the market at the end of the system's life seemed almost a generation apart from the humble of 1983 releases that kicked things off.

"The first three games released for the system were Popeye, Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr.," says Kalata. "One of the last was Takahashi Meijin no Boukenjima IV (Adventure Island IV). The former were single screen arcade conversions with a small number of levels, with sparse black backgrounds and simple music. The latter is a sprawling adventure, featuring dozens upon dozens of screens with non-linear exploration, an expansive inventory, substantially more detailed graphics, a full soundtrack, and a password system to save progress. They may as well be on different systems."

For both Japanese gamers and a considerable number of Americans, gaming and game design came of age on the Famicom. Few people "play Nintendo," these days, but millions continue to play Nintendo. The Famicom proved to be one of the medium's most rock-steady pillars of inspiration, one whose influence remains strong three decades on.

Next: Sega's Home Debut