The best time to make a new Discworld game was 10 years ago – the second best time is now

Britain’s best fantasy author is criminally overshadowed by its worst. But video games have the power to redress the balance.

Something extraordinary happened over Christmas: I took my kids to see a big screen adaptation of The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents, starring Hugh Laurie and Emilia Clarke, who are Big Name Actors from Popular Things. This is significant, because it’s a Discworld novel. And Discworld has never quite become the juggernaut that it always felt like it ought. To my absolute shock and delight, it remained a story of Discworld in its translation to a CGI cartoon for children. It’s remarkably faithful to the book, which is just one in a series that’s dozens long. Rincewind and Twoflower even have brief cameos. I might have welled up at the sight of Terry Pratchett’s name in the opening credits, because I realised this was my kids’ first exposure to his wonderful mind, and vowed to encourage them to explore it further if they showed interest.

I can’t remember how old I was when I first became aware of Discworld, Terry Pratchett’s extraordinarily rich and tonally diverse fantasy universe in which he set 41 of his fifty-odd novels, not counting the myriad spin-offs, atlases, encyclopaedias, and novelty in-universe diaries, but definitely counting the one he wrote with Neil Gaiman which was adapted into a beloved TV miniseries on Amazon Prime Video in 2019 and did so well that it somehow got renewed for a second season despite being conceived and marketed as a one-off (which is the exact opposite of how Netflix runs things, but that’s a moan for another day).

The success of Good Omens is relevant here because, well, it’s proof positive that we’re still captivated by the creations of Terry Pratchett. For those of us of a certain age, his children’s literature (Truckers, Diggers, Only You Can Save Mankind etc) were formative experiences in the way that a certain wizard-based series was for kids who came after. For many of us, Pratchett’s works were rare examples of books that teachers made us read, which we actually enjoyed.

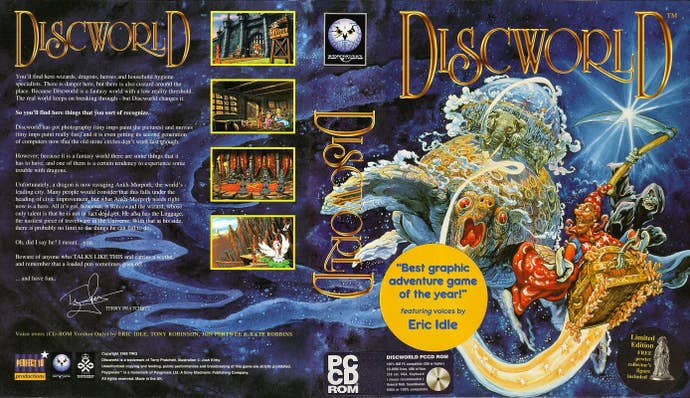

And yet, somehow, my first encounter with his most celebrated work, the Discworld series, wasn’t The Colour Of Magic (the one you should read first, it being the first) or Mort (the one everyone says you should read first, unless they’re trying to get you to read Night Watch). It was a point-and-click adventure game called, er, Discworld. And because I was a child and also dumb, I assumed it was called that because it came on CD-ROM.

CD-ROM was a relatively new thing for video games at the time and something of a technological revolution: almost overnight, games which would before have shipped on seventeen floppy discs and had no multimedia credentials to speak of (multimedia was a huge buzzword in the mid-90s because everyone in the past is an idiot) were shipping on a single CD-ROM, a medium which offered around 700 floppies worth of storage space, and game studios were eager to fill that cavernous void with all the multimedia you could ever gorge on. Full-motion video! Smooth animation! The entire game voice acted, by real people, in such high quality you could actually make out what they were saying! We’d never known the like. It was one of those revolutions, along with the 3D accelerator and the high-definition TV, that truly felt like a massive leap ahead.

And Discworld was well-poised to take advantage of it. The game, an obtuse point-and-click in the style of Lucasarts but nowhere near as good (look, mechanically it was a bit crap) employed the talents of people whose voices you actually recognised. Most notably that of Eric Idle, the Monty Python cast member who is sort of simultaneously everyone’s favourite but also the one who nobody says is their favourite because John Cleese is more popular and Michael Palin is more distinguished.

Rincewind is one of Pratchett’s most beloved characters (although one he himself didn’t enjoy writing very much, infamously describing his role in the story as “to meet more interesting people”), and Idle did such a marvellous job of voicing him that subsequent interpretations of the character have felt deeply wrong, no matter how book accurate (he’s been brought to life by a number of comedy actors over the years, including Nigel Planer in the audio books and David Jason in the terrible TV adaptation in which David Jason is about forty years older than the character is supposed to be). As well as Eric Idle you had comedy juggernauts like Jon Pertwee and Tony Robinson filling out the roles alongside Kate Robbins off Spitting Image and a talented upstart by the name of Rob Brydon.

The game was successful enough to spawn two sequels, Discworld II: Missing Presumed and Discworld Noir, the latter of which is rightly considered by many to be the best of the three. And Rincewind isn’t in it, which rather proves Terry’s point. As mentioned, the games are not especially good in terms of gameplay or mechanics. They’re faintly interactive cartoons, overly wordy, and obtuse to the point of distraction. For the most part, your role in them as the player is to exhaust dialogue options. Progress is nigh-on impossible without consulting a walkthrough (not an easy thing to get a hold of if it’s 1995, you’re 11 years old, and your mum doesn’t see the point in “getting the internet”).

That first Discworld game barely qualifies as a game. But good lord it is funny, and endearing. The script is rammed with puns to such a degree that it sails past “annoying” and lands at “impressive commitment to the bit”. The character sprites are more engaging in 100 pixels and three frames of Not Lipsynced animation than some modern games can manage with half a million polygons. Sumptuous background art hints at the grand fantasy world of the source material, and it’s all brought home by a delectable soundscape of Radiophonic Workshop sound effects and the most captivating twiddly music ever rendered in General MIDI. It’s a marvellous package, a standout work for the time, and crucially, it got a lot of kids into Discworld. I was one of them.

Video game adaptations have a sort of recurring habit of introducing cult literature to a wider audience. Christmas Day 2022, the first Christmas Day with a king’s speech in well over half a century, was more notable in television terms for the release of Blood Origin, a Witcher spin-off series that told the origins of Witchers, The Wild Hunt, and showed The Conjunction of the Spheres on screen for the first time. A lot of people thought it was crap (I enjoyed it), but the point is that it’s unlikely to have ever happened were it not for the broad success of CD Projekt RED’s The Witcher series of games, which the TV series has little to do with, but to which it doubtlessly owes its existence.

It’s possible that, had the games not existed, Netflix would have one day got around to adapting a fantasy novel that was pretty obscure outside of its native Poland (hey, they’ve adapted a lot of niche stuff), but the likelihood of Henry Cavill being involved in that timeline is zilch. Zero. Nowt. And therefore, you can very reasonably argue, the existence of the games was pivotal to the show's success – in terms of setting alight the public’s perception of the series, and flagging the interest of Superman. Without the games, Geralt of Rivia might have been played by an unknown with little draw. Or worse, some kind of dreadful Australian soap actor. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

I’m not suggesting for a second that a new Discworld game would propel the series to Kryptonian heights. But consider The Wolf Among Us; I’m sorry to do this to you, but I have to now point out that it came out nearly a decade ago, in October of 2013.

Considered by many to be the Actual Best Telltale Game, The Wolf Among Us came along during the Telltale boom that followed their extraordinarily successful adaptation of The Walking Dead. Extraordinary in the sense that it is a piece of Walking Dead media that’s actually good: an astonishing feat given how turgid the source material is, and not to mention the aggressively f**king dreary TV series that the game was arguably spun off from.

The Wolf Among Us is so beloved a game that the planned sequel has survived, at the time of writing anyhow, the death of Telltale itself: it’s due this year, in fact. And it’s a curious thing, because this is a prequel to a series of graphic novels which, while certainly enjoying considerable cult status among Comic Readers, isn’t exactly the sort of funnybook that your grandad could name (in stark contrast to, I dunno, Superman or, uh, The Walking Dead). They’re page-turners, brimming with lovely ideas, telling a grand epic of storybook characters exiled to the real world.

Like Discworld, it plays with fantasy tropes to weave allegory and satire out of goblins and sorcery. I mean, it starts to fall apart a bit when you find out that the whole thing is an incredibly ham-fisted metaphor for The Situation in the Middle East written by an unapologetically neoconservative American. Which you could get past until one of the characters all but stands in the middle of the frame and says “by the way, this whole thing is a ham-fisted metaphor for The Situation in the Middle East”. But the artwork really is nice!

And, look, given that Terry Pratchett was coming from a broadly similar place in his mining of folk tales as a basis for holding a warped mirror to reality (albeit with vastly different sensibilities and considerably more wit), it’s tantalising to imagine a time where a Telltale style narrative adventure enjoys similar success in the world of video games. There’s always a clamouring for the Pratchett-esque: the entire Fable series is testament to that, as is the bitter resentment that bubbles up online every time Microsoft does a showcase that fails to deliver an update on the mythical Fable 4. For reference, that’s every showcase since July 2020.

The Witcher, The Wolf Among Us, Fable, and countless others show that there’s a healthy appetite in gaming for story-rich adventures that put unique spins on folklore and fairy tales. In Discworld, there is a second-hand set of dimensions absolutely rammed with the stuff. It's as captivating, hilarious, and relevant as ever, as the recent movie deftly proves.

But a low-key SKY ORIGINALS movie every decade or so doesn't do it justice. Nor does a lavish new set of audio books featuring the likes of Colin Morgan and Peter Serafinowicz, delectable as they are (the productions, not the actors, although actually yeah).

Narrative adventure games have enjoyed a massive renaissance over the last decade or so. They've never been better. And I'd argue that we've never needed Terry Pratchett's humour, his warmth, his uncanny knack for putting complex social and economic issues in simple terms, and his generosity of spirit more than we do now. He's an institution that will never turn against us, and a hero who will never disappoint.

It's time.