New Deer is Blazing a Trail for Western Animation in Japan

How one animation enthusiast hopes to use games to broaden Japan's cultural horizons.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Ever since Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball hit it big, Japanese animation has been a fixture in the U.S. In some parts of Europe, anime has been popular even longer than that. Where import games used to have all hints of anime scrubbed from their box art, usually replaced by muscular airbrushed men, video game enthusiasts have come to accept Japanese games and anime as more or less synonymous. They're a given now.

But what about the reverse? We rarely think about how American and European animation fares in Japan. Sure, Disney characters may be even more popular in Tokyo than in Anytown USA, and Japan's Bart Simpson fad is still running strong, but what about other animation? How do American shows like Steven Universe or French films like The Triplets of Belleville fare over there? Do they have the visibility that something like Naruto enjoys in the U.S.? Or is Japan as resistant to import cartoons as it used to be to import video games?

According to Nobuaki Doi, it's more the latter at the moment. But he hopes, through his work, to help change that. "There's maybe a little bit of an aversion among Japanese audiences for types of animation that don't fall into, say, normal CG or Japanese anime," Doi muses. "But there is an audience for art films in Japan, and that's where we're beginning our work with this project of trying to introduce foreign animation into the market."

Doi works as president and CEO of a distribution company called New Deer, which he compares to western companies like GKids (the distributors of Studio Ghibli films in the U.S., among others). Since the company's establishment in 2015, Doi says, he's made a mission of bringing esoteric Western animation to Japan. "My first project has been to introduce specific foreign animators from various countries around the world in Japanese cinemas as feature films," he explains.

"Currently, we distribute The Boy and The World, a feature film from Brazil, and The Girl Without Hands, from France." These films aren't exactly box office titans on the scale of The Incredibles 2, but to Doi, that's part of their appeal. "Both of these movies are features, but both were created as private projects. Their directors helped animate almost all frames."

While this handcrafted touch certainly isn't unheard of in Doi's native country—Ghibli head Hayao Miyazaki is famous for his habit of poring over and sometimes editing the individual cels of his studio's films—it certainly stands in contrast to the standard processes of anime. The anime industry has become famous for its unforgiving churn, demanding long hours for low wages with deadlines running so tight that episodes sometimes air in a draft state that has to be heavily refined for publication on physical media. Doi is drawn to the dynamism that foreign animation is able to enjoy, free of those harrowing conditions.

"The main interest I have in foreign animation, especially independent ones, is their unique style," he says. "The way their creators are able to express their own particular thoughts and points of view. I also appreciate the way it provides a different viewpoint on the world. Works that can establish a different relationship to society are what I'm interested in introducing here."

Doi also appreciates the more experimental processes independent western animation incorporates. (He admitted to recently purchasing some Isle of Dogs merchandise.) "More than any particular technical development," he says, "what interests me is the use of unusual media such as puppets, colored pencils, or ink. I also enjoy the attitude some creators have toward those media. I love the combination of a creator's attitude and use of 2D media that don't fall within the usual norms of mainstream animation."

His enthusiasm for foreign animation led him to create a career out of it—initially academic, but ultimately commercial. "My background was originally in academia," he says, "where I studied animation from around the world, such as Yuri Norstein. I began this project so that, at the more business-oriented level, I can introduce foreign independent animation to Japan."

Given the enormous crossover between Japanese videos games and anime, it seems somehow fitting that Doi has chosen to pursue video games as an avenue for sustaining western animation in Japan. New Deer's video game efforts reflect two different ambitions: creative and financial.

On the creative front, Doi sees in games the potential to explore creative concepts that can't be fully expressed in traditional media. "Because of my work, I'm connected with a global network of independent animators," he explains. "People like David OReilly and Michael Frei, a Swiss animator. [This allows me] to bring traditional animators into the game world.

"In the films I've promoted so far, the real focus has been in expressing or introducing the creator's worldview. Because games are nonlinear and have a different relationship with space, they may open up even more points of view on that unique perspective."

At the same time, not all of Doi efforts are quite so high-minded. "Aside from that, there's money in the games industry," he says, laughing. "That's attractive!"

While he aims to explore gaming's potential for artistic expression through New Deer's ventures, Doi also sees financial incentives in gaming that can be harder to come by in the smaller, more niche-oriented world of independent film. "Because of the changes in media, it's very difficult to make any money in short films. You can produce something and put it on YouTube or Vimeo or whatever, and people will look at it, but they're not going to pay money for it. So, one way creators can raise funds is by doing advertising work.

"However, gaming seems to be a better avenue. Similar to independent animation, you can produce a small game without a huge staff. Someone like David OReilly can produce a game by himself, mostly. If it becomes a hit and brings in money, it becomes a survival strategy for these independent animators."

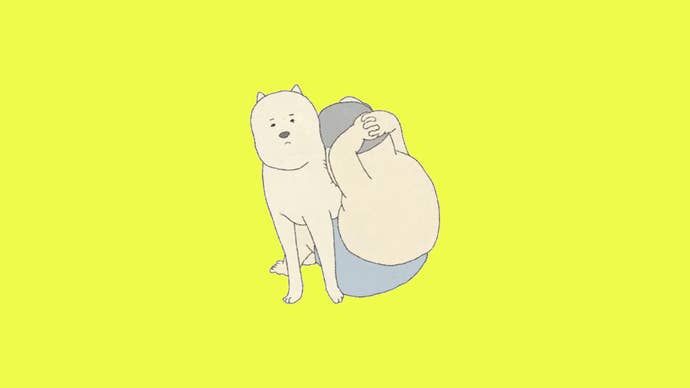

New Deer's first game project—a collaboration with animator Atsushi Wada and Playables—launches later this year. Called My Exercise, it's more of a digital novelty than a proper video game. The brief sample I've played of it consists entirely of tapping the space bar of your computer to make a fellow with short hair and a soft belly perform a sit-up. That's it.

What My Exercise lacks in depth it makes up for with charm. Your avatar's sit-up companion is a nonplussed-looking dog who helps out by standing over the exerciser's legs, hold him down as he struggles to work out. With each tap, your avatar performs a sit-up, smashing his face slightly into the dog's fur. Hold down the space bar, however, and you'll push further and further into the dog's flank, comically folding into its and fur. Release and the exerciser will slowly, comically detach from the dog. And after you've managed to complete about a dozen sit-ups, a girl sits down beside you and claps encouragingly.

It's a silly little blip of a game that marries lively animation to a quirky game concept. It's a fascinating cornerstone for a business… but given the unique nature of the business New Deer is up to, it seems completely appropriate.