Never Been So Much Fun: The Making of Cannon Fodder

Eurogamer's Joel Snape explains how Sensible Software turned the horror of war into a '90s classic.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

20 years ago -- nearly a decade before Medal Of Honor forced players to storm Omaha beach under merciless artillery fire, and a full 15 years before Call Of Duty ended a mission with everyone dying in the radioactive aftermath of a nuclear blast -- one game taught a generation that war is, indeed, hell.

If you were playing games in 1993 -- especially if you were playing them on the Atari ST or Amiga, the concerned parents' 'educational' alternatives to the SNES and Megadrive -- you probably remember Cannon Fodder's 'Boot Hill' intermission screen, where tiny, brave, 16-bit civilians were waved through a door by a recruitment officer, only to (almost) inevitably reappear as gravestones dotting the surrounding landscape. It's hard to forget.

"That's a story about why iterative development is good," says Jon Hare, co-founder of Sensible Software and designer on the game. "Because that would have never happened if we'd worked it out at the start. Initially, we had this sort of recruitment hut between the levels, but we didn't like it, so we changed it for a hill. We also had the ranking-up screen, which is pretty standard games stuff. And then, one day, we said 'Well, what if you saw the names of all the people who died in the last set of missions?"

"Suddenly you realised how many people you were wasting to do every level, and that seemed to have some sort of correlation with real war. So we decided to not allow you to click away from the list, so you had to see the people who died. And then you're really thinking 'Oh my God.' We put the sad music over the top of the recruitment screen, which was an instrumental version of an old song I wrote it for the first person I fell in love with, back when I was 18 and really fell apart in that way you do at that age.

"And then we thought about it and looked at the hill and went 'Well, why don't we put up a gravestone?' Which is kind of a novelty at at first -- but by the time you get to about level 18 that hill is full of them. That's all about iterative design -- making a game, running it, and seeing how good it is. From a hut, to a hill, to the graveyard. It's about letting things naturally evolve."

In fact, Cannon Fodder as a whole is a near-flawless example of iterative development in action. Sensible Software, founded by Hare and schoolfriend/bandmate Chris Yates, had already made a name for themselves with strategy game Mega Lo Mania and the wildly addictive Sensible Soccer, so a return to the top-down approach seemed like the obvious choice.

"That's all about iterative design - making a game, running it, and seeing how good it is. From a hut, to a hill, to the graveyard. It's about letting things naturally evolve."

Jon Hare

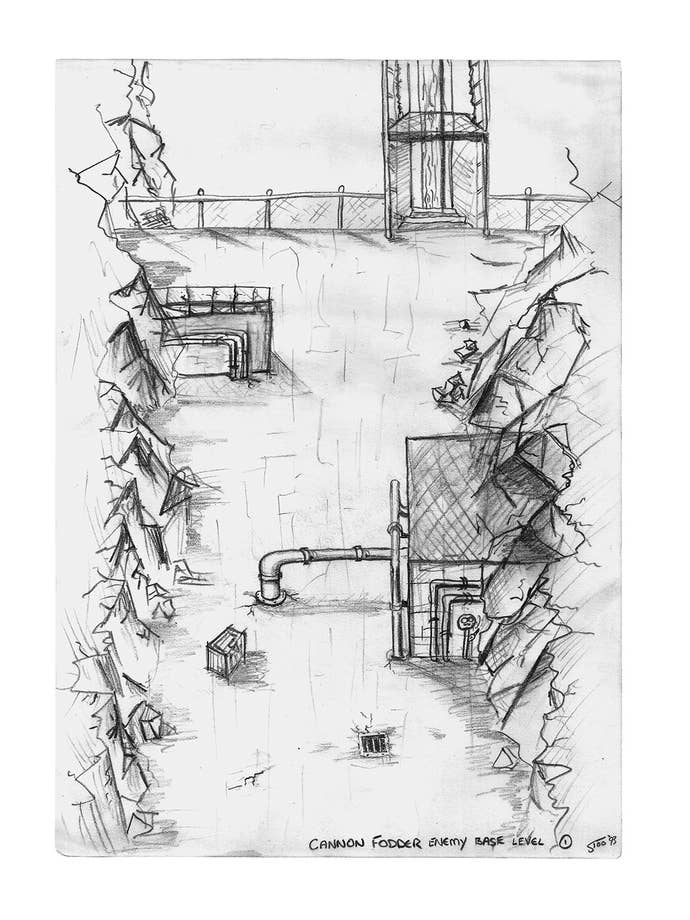

For their next game, Hare remembers, they knew they wanted to make 'a sort of Rambo game with a troop element to it,' but the initial brief wasn't much more complicated than that. "In retrospect the ideas were quite loose," says Stuart 'Stoo' Cambridge, who took over lead art duties for the first time on the game. "I liked the idea of taking a strategy game and making it fun. I don't remember too much about a design document compared to what you'd see today, it was more like a couple of pages of notes. When you look at the original idea, you've got this major evolution going on throughout the project."

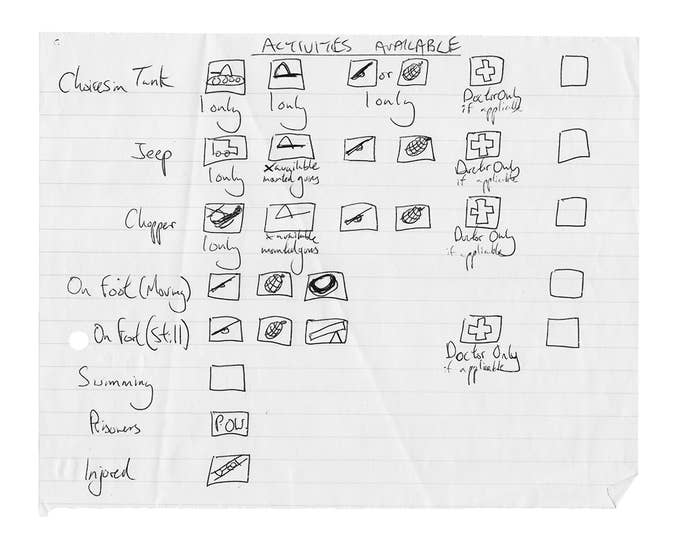

In keeping with their usual development style, Sensible ignored traditional storyboarding in favour of plotting out levels on graph paper and tinkering as they went along. Ideas discarded early in the development process included specific soldiers having specific skills -- only specialists being able to pilot choppers, for instance -- and having a degree of autonomy. Instead, the team spent a long time fine-tuning what still stands up as one of the most simple, elegant control schemes in gaming history, which used nothing but a two-button mouse to manage everything from movement and shooting to piloting helicopters, firing homing missiles, splitting the team up and issuing orders to individual units.

"What I always thought was brilliant was that you could just click and click and click and the game would remember the path you told your guys to take," remembers Cambridge. "There's nothing worse when a game's great and the control system's awful -- it's supposed to be the most important part of the experience."

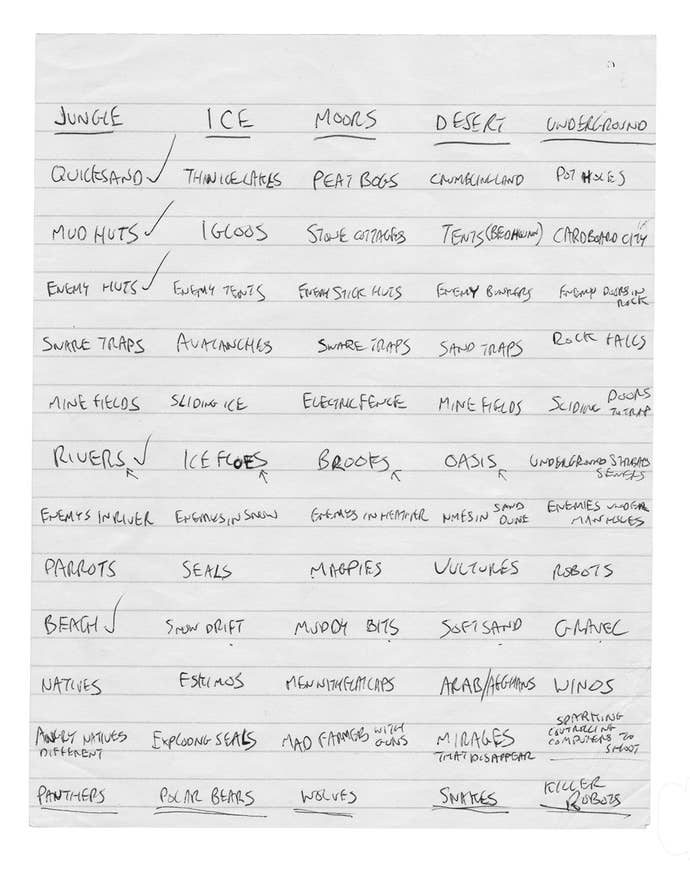

Hare focused on crafting one of what was, at the time, one of the most elegant learning curves around, introducing a single new element -- grenades, rocket launchers, jeeps, tanks, helicopters -- with almost every new 'block' of levels. The one mis-step is the infamous Mission 19, an infuriating puzzle that involves getting three members of the team to stand on separate pressure pads while also piloting a helicopter. But this was 1993, when there was never a guarantee of seeing the closing credits for anything, and the game's most punishing level became a badge of honor for those who'd got through it, making the romp through the final levels, if anything, more satisfying.

Meanwhile, as with the control system, the technical limitations of the Amiga's graphics setup forced the team to seriously consider their use of resources. "Before I even started the animation, I did a lot of work with color palettes," recalls Cambridge. "We had to do everything with a 16-color palette, we just couldn't do everything in the way we wanted because we ran out of colours. We'd get exactly what we wanted and then realise that we still needed a blood color, or whatever.'" The result, though, still looks incredible: because literally every pixel of the animation has been scrutinized and slaved over, watching those tiny men bleed out after taking a stray round or stepping on one of the game's barely-visible booby traps -- terrifying, the first time it happens -- is an agonizing experience.

Cannon Fodder launched to largely rave reviews, though it wasn't so beloved of tabloid newspaper in Sensible Software's native UK. The choice to feature a poppy on the loading screen provoked the charitable, soldier-and-veteran-supporting organization The British Legion -- a group that uses the poppy as its symbol -- and things weren't helped by former Damned frontman Captain Sensible's theme tune -- jaunty ska number War's Never Been So Much Fun (main lyric: 'Go up to your brother/kill him with your gun'). But the controversy didn't hurt sales, and Cannon Fodder easily passed the 100k mark on the Amiga alone, before making the move to other formats.

A sequel followed a year later, and while it improved on the original in certain respects -- the difficulty curve was a touch curvier, and the water sections, in which you couldn't shoot while trudging through, were removed entirely -- the addition of time-travel, aliens, and an often-jarring color palette (so much purple!) means it's not as fondly remembered. "I personally thought that it was a big mistake to go with time travel," says Cambridge. "We were originally going to do some cutscenes that explained why it was happening, but they never happened because of time constraints and so it was really confusing. I think if we'd done number two as another straight war game, we could have led up to the time travel stuff for a third game."

A third game, of course, only finally happened in 2011, after Russian publishers Game Factory Interactive acquired the rights to the name from Codemasters -- making Sensible's involvement redundant. It launched in Europe and America in 2012 to mixed reviews -- most pointing out the Mission 19-like care that you suddenly had to apply to every single level -- but crucially, it just doesn't really feel like Cannon Fodder, mainly thanks to the decision to go with polygon artwork.

"I think that by using 3D you're changing the way the game looks and feels for no reason," says Cambridge. "I like 3D, but there's nothing wrong with the way things work in the old game. In a 2D game, what you can achieve these days is absolutely stunning. If you did Cannon Fodder on a phone, you could do so much without ever needing to go 3D."

Will Cannon Fodder ever make it to the phone? Short answer: probably not. Sensible doesn't have the rights to the name, so any remake wouldn't bear the name, and the team has other projects, interests and families now. But the original game still stands as a phenomenal example of what you could do on the old formats, and why less is sometimes better.

"It was just a fantastic way of working," says Cambridge. "You can't really do things now like we did them then, unless you're going to be totally independent and have people supporting you while you do. You can't do that on a big-budget game, unless you're prepared to make a massive loss and you don't care about money." Hare, meanwhile, sees a trace of the Cannon Fodder development ethos in the current crop of games -- and it's a plus.

"What really matters is being willing to evolve. To make any game, sometimes you have ideas and think they're really good, but then you implement them and they don't work. If you're ruthless about editing the crap out of your game, or manipulating it to make it better. A lot of people love Grand Theft Auto 5 right now -- I can't imagine the stuff they've taken out of that game to make it as good as it is. You don't end up with that many good things without taking things out." The hut, then the hill, then the graveyard. That's how memorable moments happen. War really never has been so much fun.