Neo Geo Pocket Color: The Portable That Changed Everything

On the 16th anniversary of SNK's portable powerhouse, a look back at all that made it special.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

My affinity for portable games makes me a real aberration in the gaming press. Among gaming fans, really.

Don't get me wrong, I enjoy my consoles; the impossible tangle of wires and cables next to my desk proves it. It's just that where everyone else gets angry when an Xbox One game doesn't output at 1080p resolution, I get angry when a Game Boy screenshot's resolution isn't a faithful multiple of 160x144 pixels. Or worse, when it's a JPEG. My god, people, have you no decency?

But this fascination is a relatively recent development for me. I've been hooked on video games most of my life, which means all the way back to the beginning of the '80s, but I've only been a dedicated handheld enthusiast since around the time the Game Boy Advance launched. I missed the entire classic Game Boy's life, aside from a handful of greats I played on Super Game Boy — yes, I was so married to big screens (well, relatively big; this was the '90s, after all) that I would only play portable games on a console. Game Gear always seemed fascinating but improbably pricey. Lynx was an amazing novelty.

The Game Boy Color offered my entrée into handheld gaming, but even then it felt more like a distraction from all the cool things happening on PlayStation, Nintendo 64, and Dreamcast. Those consoles were literally reinventing what the words "video game" meant with the likes of Super Mario 64 to Metal Gear Solid. Game Boy Color took all those cutting-edge first-person shooters and turned them into 2D side-scrollers. Rare's Conker was lewd, angry, and disgusting on N64, but his Game Boy Color adventure stuck to the original toothless and cloying rendition of the character. And that was pretty much portable games in a nutshell: Years behind, geared toward kids. And then the Neo Geo Pocket arrived, and everything changed.

When you think about it, the NGP (not to be mistaken for Sony's bizarrely coincidental codename for Vita, Next Generation Portable) was a strange creation. It makes a certain amount of sense that SNK would jump into the handheld market in the late '90s; by that point, everyone else with their own console had done the same thing as well. Nintendo, Sega, Atari. Even NEC (with the TurboGrafx-16-compatible TurboXpress) and Bandai (via its freshly announced WonderSwan) had gotten in on the act. So obviously the company behind the powerful Neo•Geo needed to do likewise.

But that's the thing: The Neo•Geo made its mark through its premium status. The most powerful console of the 16-bit race by far, the Neo•Geo also managed to be the most expensive. It was the Cadillac of consoles, a literal arcade-quality experience at home (with a little tweaking, you could play arcade boards on your home system). Handheld systems, on the other hand, existed at the opposite end of the spectrum. It's not that high-powered handheld hardware can't exist; rather, the needs of high-powered hardware undermine the needs of portable gaming.

The Game Boy succeeded not because the world was desperate for a dinky-low resolution screen whose four putrid shades of grey collapsed into a blurry singularity every time the screen scrolled, but rather because that miserable little screen was so easy on the wallet both in terms of up-front hardware costs and long-term battery expenses. Sure, Sega managed to compress the Genesis hardware into the glorious Nomad and even created the mind-boggling portable Genesis/Sega CD/Discman hybrid CD-X, but both of those systems could suck a set of batteries dry in a matter of an hour or two.

How, then, could SNK hope to produce a portable system as powerful as the Neo•Geo, a machine whose 2D graphical capabilities remained unmatched by other consoles even as the millennium drew to a close? The simple answer was: They didn't. In fact, they didn't even bother trying.

The modest premium experience

The genius of Neo•Geo Pocket came from the fact that SNK didn't attempt to create the most stunning handheld experience ever. The system didn't even begin to compare to the Nomad in terms of raw power. It even lagged behind Atari's Lynx, which had debuted nearly a decade prior; the original Neo•Geo lacked a color screen.

But those black-and-white visuals tipped the designers' hand. They weren't out to push the boundaries of handheld technology. Rather, SNK decided to work within the parameters Nintendo had established with the Game Boy and excel within those limitations. Bandai adopted a similar tactic with its WonderSwan; after a decade of watching Nintendo walk all over superior competitors with a piece of hardware that strained the limits of minimum technical acceptability, would-be rivals finally cottoned to the secrets of Game Boy's success: Be crappy, but be crappy with panache. These new systems (along with the disastrous Game.com) were the first handhelds to attempt to beat Nintendo at its own game.

Of course, Nintendo hadn't been sitting still throughout the '90s. The Game Boy provided a stable source of income for the company, but Nintendo always had an eye toward the future, developing new portable systems in the background. Virtual Boy was a dark, apocalyptic future. Project Atlantis was a future that never came to pass. But the R&D divisions kept churning through hardware iterations, and so Nintendo was ready to deal with these new challengers by changing the rules. A week before Neo Geo Pocket launched in Japan, the Game Boy Color debuted, immediately rendering SNK's new system and Bandai's upcoming WonderSwan launch obsolete.

To their credit, SNK was quick to respond. The Neo Geo Pocket Color arrived less than five months later, giving the platform the visual boost it needed to convey its technical edge over Game Boy Color. Still, being caught flat-footed didn't do SNK any favors; it left the original Neo Geo Pocket dead in the water, doomed the moment it debuted. While the Color model proved to be backward-compatible with all but a handful of black-and-white titles, only about half of the releases for the color model supported monochrome mode.

Still, with the move to color, players could more easily appreciate what a fantastic little machine SNK had created. Boasting a 16-bit processor and three times the RAM of Game Boy Color, NGPC could generate more detailed and colorful graphics than Nintendo's system. Sprites were larger and moved with fluid grace, animating with a degree of buoyancy never before seen on a handheld system. Even Lynx and Game Boy Color tended to generate choppy, sputtery graphics at a distractingly low frame rate, but that wasn't a concern for NGPC. And SNK put that technical prowess to work the way it knew best: With loving, pint-sized recreations of its arcade games.

Portable punch-up

The Neo•Geo platform had gotten off to a shaky start back in 1990, squandering its unprecedented visual quality on derivative and unremarkable games. NAM-1975 and Magician Lord looked incredible, but they didn't offer anything beneath those slick visuals to justify the staggering cost of their overstuffed cartridges. It wasn't until Capcom codified the fighting genre with Street Fighter II that SNK found its calling, launching multiple one-on-one brawling concepts in rapid succession. For every forgettable Aggressors of Dark Kombat, the Neo•Geo saw a breakout hit like Fatal Fury, Samurai Shodown, or The King of Fighters.

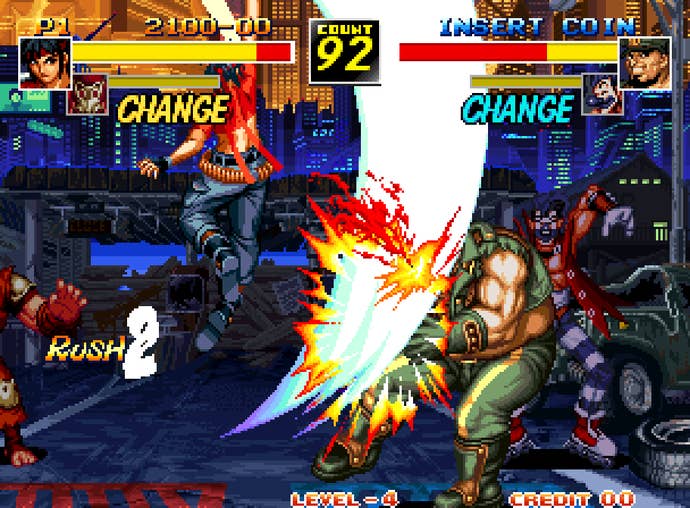

SNK and its dedicated NGPC developers like Sacnoth and Yumekobo did a remarkable job of converting these complex, eye-popping arcade fighters to a screen with a mere eight lines of resolution more than the Game Boy offered and a measly two buttons. These weren't the first portable fighters by any means; in fact, King of Fighters R1 and Fatal Fury First Contact weren't even those series' first handheld outings. Both had already made appearances on Game Boy courtesy of Gaibrain. But those 8-bit efforts paled compared to the silky smooth and incredibly responsive versions that NGPC owners enjoyed.

As much of the credit for the sheer playability of NGPC fighters had to do with the external hardware as it did what was inside. Yes, the system's beefy processor and healthy RAM cache facilitated quick, responsive game design. But the system's wide horizontal format, styled almost like a compact Game Gear, made the NGPC comfortable in the hands. And its control interface — a short, recessed stick that socketed into eight directional grooves — remains many fan's all-time favorite form of digital input.

The system's so-called "clicky stick" neatly solved the problem of how to integrate a more responsive digital interface than Nintendo's time-tested D-pad while at the same time maintaining a low profile visual design that would minimize wear and damage to the stick. Both Sony and Nintendo borrowed the general concept of the NGPC's stick for the PSP and 3DS analog sliders, though many would argue with less success.

The precise responsiveness of the NGPC's stick made top-class fighting games possible. Advanced moves proved a dream to execute on the system, and the portable's lack of buttons (two face buttons versus the Neo•Geo MVS's four) was resolved in software: "Light" fighting moves required a quick tap of the buttons, while "strong" actions used sustained presses. It was a simple and elegant solution — and it even worked when Capcom's Street Fighter II characters (normally controlled with six buttons) showed up in first-of-its-kind company crossover fighter SNK Vs. Capcom: Match of the Millennium.

The NGPC wasn't strictly limited to fighting games, either. Its arcade conversions included great puzzlers like Magical Drop and classics like Pac-Man, which came with a small accessory that allowed players to constrain the control stick to cardinal directions for precision play. Perhaps most impressively, the system played home to a pair of Metal Slug adaptations that compensated for the downscaled visuals by expanding the scope and complexity of the adventures, with an expansive world map and multiple routes to explore across playthroughs.

Achilles and his heels

All of this sounds amazing, right? And yet here we are, speaking of NGPC as a historical curiosity. An obscurity. But a system this great should have had a happy ending, right? It should have crushed all who stood before it!

Of course, that didn't happen. Like all who dared to challenge Nintendo's portable empire before the age of smartphones, NGPC failed to set the world on fire. In the end, a mere two million units made their way into gamers' hands. Unlike WonderSwan, SNK managed to give the console a global release. Even so, it languished in obscurity.

Neo Geo Pocket Color's ultimate failure boiled down to two factors: Software support and retail reach.

While SNK and its close partners did a bang-up job of producing top-flight software for NGPC, they represented a small coalition of talent. Compared to the hundreds of studios banging away at Game Boy software and the dozens of studios Bandai collaborated with on WonderSwan, NGPC couldn't sustain the frequency of releases necessary to be fully competitive.

The system also lacked sufficient diversity in its lineup; its arcade-focused library was undeniably impressive, but handheld fans in the late '90s had moved beyond those quick, bite-sized experiences and more toward games like Pokémon. The NGPC wasn't without its share of RPG-like releases, including Dark Arms: Beast Buster and the highly regarded SNK Vs. Capcom: Card Fighters Clash, but they were few in numbers.

Worse, it was difficult to find NGPC games. Like NEC before them, SNK lacked a strong retail presence and the network necessary to get its games into stores. American handheld enthusiasts initially had to purchase the Neo Geo portable online — and in 1999, Internet shopping had yet to find mainstream traction. Eventually, the system made its way to major retailers like Wal-mart and Toys 'R Us, but only well after launch.

Theoretically, SNK's big partnership (a cross-platform collusion with Sega) should have been a huge boon for the NGPC. Sonic Pocket Adventure — developed by Dimps, who would later go on to make the Sonic Advance titles — was easily the tentpole title for NGPC upon its American launch. Even more intriguingly, Sonic Pocket Adventure connected with Dreamcast through a special cable, as did several other NGPC games. This probably would have worked out better if Dreamcast didn't already have its own built-in portable element with its VMU memory cards... and, obviously, if Dreamcast had survived longer. Unfortunately, SNK hitched its wagon to the wrong horse.

Cut loose

Not that it might have made any difference. Any possibility the NGPC might have had of establishing itself in the long term was cut off in 2000 (a mere year after the U.S. launch of the system) when gambling manufacturer Aruze bought SNK. Aruze's first act as the new owners of SNK was to kill the NGPC outside of Japan. The popular rumor was that Aruze intended to scavenge NGPC screens and the rewritable flash chips inside NGPC game carts to integrate into their pachinko machines. While that was probably just Internet hysterics and paranoia at work, there was little question that the portable system had no place in Aruze's vision for the SNK brand. The platform was killed quickly in the U.S. and Europe, and vanished soon after in Japan.

The swift and unceremonious severing of the NGPC's lifeline meant that several planned U.S. releases stalled out; most infamously, strategy RPG Faselei! was manufactured and even released in Europe, but its U.S. version — slated to launch mere weeks after the buyout — never happened, resulting in an unevenly distributed game that sells for hundreds of dollars... assuming you can even find it in its rare boxed form. Meanwhile, games in development, including announced sequels to Magician Lord and Ikari Warriors, were shut down and never completed.

The Aruze buyout demolished the NGPC's life and legacy in a single motion. What little platform inventory remained in retail channels and warehouses was eventually dumped onto the market via budget packs (some of which, curiously, included unreleased titles like Faselei!), and the system was quickly forgotten as the portable gaming world moved along to more advanced platforms like GBA and PlayStation Portable. Aside from the occasional discovery of prototype games (such as the Castlevania-like Magician Lord 2), the NGPC has all but vanished from the world's radar.

Still, NGPC had its place. It served as a technological bridge between the 8-bit portable era and the GBA, a proof-of-concept that a handheld system could offer more robust technology and still hit all the same success points that worked in Game Boy's favor. Its physical design found an echo in GBA, and its clicky stick paved the way for modern analog sider pads.

And speaking for myself, it proved that portable games didn't have to be a compromise. While plenty of contemporaneous Game Boy Color titles managed to hook me despite their technical shortcomings, NGPC games required no such adjustments. Games like Gals Fighters, Card Fighters Clash, and Metal Slug: 2nd Mission worked on their own terms. They set out to create great game experiences and succeeded admirably, with slick visuals and deep play that sincerely felt like solid 16-bit console creations. It kindled an appreciation of gaming on the go that burns strong 15 years later.

Neo Geo Pocket Color's life may have been painfully brief, but it was nevertheless memorable for those who experienced it. Perhaps all the more so for the system's brevity, in fact.