MSX: The Little Hybrid That Could

30 years ago, two companies teamed up to create a global computer standard. Great video games were the guest of honor.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In today's world, the personal computer has become a thing of ubiquity. We take PCs for granted, a basic part of first-world life on par with television, automobiles, and indoor plumbing. Look back 30 years, however, and that wasn't the case at all. In the late '70s and early '80s, people were still trying to wrap their heads around the entire concept of actually owning a computer.

Apple had made quite a breakthrough in 1977 with the Apple II, the first truly consumer-oriented microcomputer. Over in Japan, NEC had done well with its own platform specific to that market's needs (in particular, high-resolution graphics capable of displaying intricate Japanese text). Yet these machines commanded high prices; the Apple II sold for $1200 (roughly $2800 adjusted for inflation) while the NEC PC-8001 and its descendants were even more expensive. Worse, they were simply standouts in an ocean of competing, incompatible standards.

Enter the MSX. Debuting in the summer of 1983, the MSX attempted to conquer the market by overcoming the shortcomings of other computers. It would be inexpensive, roughly a third of the price of the PC80, and it would nip the incompatibility issue in the bud by promoting a single, open, industry-wide standard hardware spec. Other computers had attempted to overcome one problem or the other, but MSX challenged both.

The MSX was not a computer per se. A collaboration between Japan's ASCII Corp. and America's would-be giant Microsoft, the MSX was a reference point, a standardized hardware spec that any manufacturer could build. The platform's creators -- particularly ASCII's Kazuhiko Nishi -- based their design around a fairly obscure PC called the Spectravision SV-238, which debuted at roughly the same time as the MSX standard and (with a little rejiggering) could be made to work with MSX software. While ASCII's marketing at the time stated MSX stood for "MicroSoft eXtended," Nishi has retconned that tagline with the claim that he intended it to mean "Machines with Software eXchangeability."

Why the Spectravision? Most likely, Nishi selected Spectravideo's new machine for its ideal combination of power and familiarity. The SV-238 had been built around widely available components, such as the ubiquitous Zilog Z80 processor and a Texas Instruments graphics card, and it included a respectable amount of memory and horsepower. In fact, the Spectravision architecture was remarkably similar to that of the ColecoVision and therefore also its Japanese contemporary, Sega's SG-1000.

As such, the MSX existed at a perfect balance point to become a significant force in the Japanese market. While more expensive than similar game consoles, the MSX was considerably cheaper than its competitors in the Japanese PC market. And while the SG-1000 eventually offered a PC-like add-on package that put it roughly on par with the MSX, that expansion also raised its price to MSX levels. The MSX spec created a standard computer/console hybrid machine that neatly met the entertainment desires of gamers and the computing needs of households. And, unlike the SG-1000, it was an open standard that third parties flocked to, ensuring a certain degree of availability for its software. Before long, MSX became quite pervasive in Japan.

Of course, ASCII and Microsoft hoped to create a global standard, but by 1983 many Western markets -- particularly the U.S. and the U.K. -- were already glutted with their own cacophony of PC standards. Most Americans had already settled on the Apple II and Commodore 64 as their computer of choice (according to their own needs and budgets), while the British gravitated toward Sinclair's Spectrum and the Amstrad CPC. The MSX offered little that those other platforms didn't, and its cartridge-based software format seemed dated by the time it reached foreign shores.

While it carved a tiny niche for itself in Europe, MSX's fleeting appearance in the United States didn't even constitute a blip. Curiously, despite Microsoft's involvement in establishing the platform spec, they did nothing to help propagate its spread in the company's own backyard... presumably because it was more interested in Windows development, which was already in full swing by late 1983.

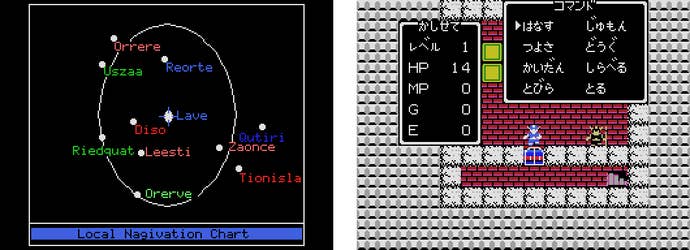

In Japan, however, MSX's was a different story altogether. It hit a sweet spot of price and flexibility, appealing to both casual computer users and software publishers alike. "Many of the hobby computers of the era - the NEC PC-8001/8801/6001/9801, the Fujitsu FM and Sharp MZ/X1 series - were lacking in decent graphical hardware," says Kurt Kalata of Hardcore Gaming 101. "Like the IBM PCs of the Western world, they were business or hobbyist machines that also happened to play games. And the games they played tended to be ones without much action, like adventure games or RPGs."

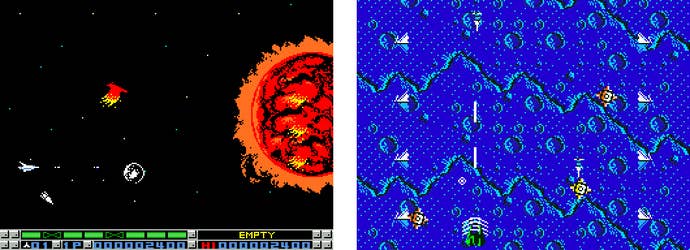

What MSX lacked in text display options -- its resolution was a mere 256 columns wide versus the 640 of the PC80 -- it more than made up for with its sprite- and color-handling features. And the machines' cartridge format, so deprecated in the West, made MSX games a matter of plug-and-play ease... not to mention far more durable than the fragile 5.25" diskettes used by most computers.

"The MSX was the first successful computer in Japan which was priced at a level that your average Japanese family would consider buying one for the kids," says Kevin Gifford, editor of Magweasel. "It, alongside the NEC PC-8801 (a much more "serious" computer at a much higher price), played home to the first generation of garage video-game designers in Japan, including people like Yuji Horii and companies like Square, Enix and Falcom who later became much better known for console games. Along those lines, the MSX isn't directly comparable to the FC (and arguably it's a lot lower-spec too), but as the most popular 8-bit computer platform of the '80s in Japan, it did a lot to create the Japanese game scene that, to Western eyes, completely blew away what Atari et al. did when the NES began to hit it big in '86 and '87."

Because the MSX shared so many elements in common with contemporary game consoles, it enjoyed a sort of Trojan horse effect. People who wanted a video game console but couldn't necessarily justify owning a standalone device for gaming only could rationalize owning an MSX for its ability to serve practical computing needs while also doing a bang-up job of running games as well. Again, both of the MSX's console "cousins" saw their creators attempt to get into that same hybrid market with the Sega SC-3000 and the Coleco ADAM, but they went about it backwards, grafting a computer onto a game machine. MSX was designed first and foremost as a computer that also happened to be really good at video games.

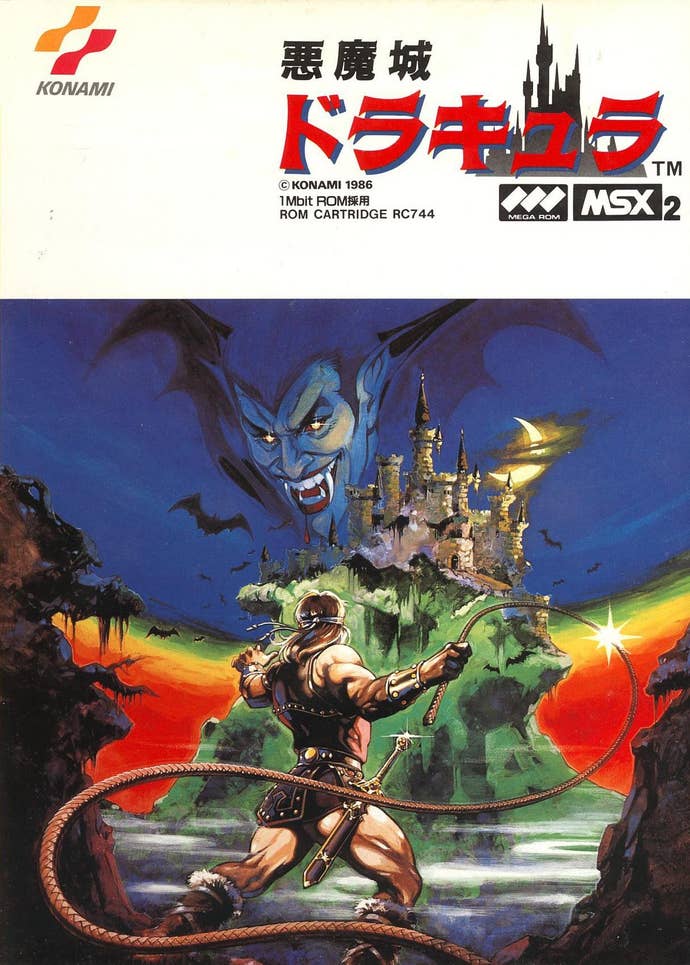

"The MSX had business uses, but since it used similar hardware to the Colecovision, it also allowed a greater focus on games," says Kalata. "While still weak in comparison to the Famicom (and even arguably to European micros like the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum), the MSX was better at arcade-style games than any other computer platform at the time in Japan. This attracted support of companies like Konami, who developed some of the best and most well-known games on the platform."

The phrase "jack of all trades, master of none" often carries a disparaging connotation. For MSX, however, that philosophy proved to be a strength. In addition to appealing to computer developers who coveted the large audience made possible by the platform's manufacturer-agnostic design, it also gave console publishers a handy second platform that could host solid conversions of their creations for Nintendo's Famicom. The MSX didn't come close to matching Famicom's sales, but it did well enough that many publishers targeted dual releases of many games to Famicom and MSX -- something that became even easier a few years later when the more powerful MSX/2 standard debuted.

Any number of familiar Famicom/NES titles made their way to MSX; a casual glance through the MSX aisle of a Japanese retro game shop will reveal a startling number of familiar titles. Even much-vaunted games seen as breakthroughs for the Famicom, such as Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, appeared on MSX as well. Konami embraced the MSX to such a degree that it actually debuted the Castlevania series simultaneously (with two similar but different games) on MSX and Famicom, while the NES version of Metal Gear that so many Americans remember fondly was actually a somewhat poor port of an MSX original title.

Still, as a gaming platform, MSX overall came in a distant second behind the Famicom in Japan. It managed to outperform Sega's muddled collective of 8-bit consoles, but the gulf between Nintendo's market leader and the MSX ultimately grew as the Famicom boom continued into the '90s, fueled in part by the growing sophistication of Famicom software (not to mention the increasingly intricate chips used to power those games).

"MSX got off to a much better start [than SG-1000]," says Chris Kohler of Wired Game|Life. "With games like Metal Gear and Dragon Quest, it certainly had a lot of support from major publishers. But in the end, the expense and complicated nature of owning a big personal computer made the cheap, toylike Famicom the clear winner for the mainstream consumer. And with that came marketshare, and with that came the majority of third parties' resources."

In the end, perhaps the problem with MSX was that its creators -- canny as they were -- failed to predict the degree to which the general public would grow comfortable with computers over the course of the '80s. While the MSX was the perfect machine for Japanese consumers in 1983, expectations and needs had evolved dramatically by the end of the decade. Most notably, the average age of computers users became dramatically younger over the course of the decade as prices and complexity dropped.

"There is always going to be a certain percentage of the population that is intimidated by computers," says Chrontendo's Dr. Sparkle. "This was especially true in the 1980s. Many MSX titles seem geared towards a teenage/young adult male audience, both in subject matter and the heavy use of kanji in the games. The Famicom 'Home Video Computer' was targeted at a much broader audience. The second batch of Famicom games, released in August 1983, comprised a Mahjong simulator and a traditional board game similar to igo. Clearly, Nintendo was marketing the Famicom at both young children and their parents."

In other words, while the MSX succeeded by bridging the computer and video game worlds for an older audience, the Famicom became a juggernaut by bridging all age groups for games alone. Still, success isn't always relative, and the MSX should definitely be regarded as a hit in Japan. Its time was ultimately fairly brief; by the end of the '80s, Japanese gamers looked to game systems like the Famicom and PC Engine, while serious computer users had the powerful PC80 successor PC-9801, diminishing the need for a device that straddled the middle ground. Yet the MSX platform helped introduce a generation in Japan to computing, and it maintains a certain fondness among Japanese consumers similar to the Amiga's cult of nostalgia in the West.

True history doesn't break neatly into self-contained eras, and the MSX stands as an important evolutionary milestone in Japanese gaming thanks to its complex combination of good ideas, logistical challenges, and -- most of all -- some pretty memorable video games.

Next: The Famicom Legacy (coming soon)