More Than Shamans and Savages: American Indians and Game Development

John Romero and others share their perspective on American Indian representation in game development.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

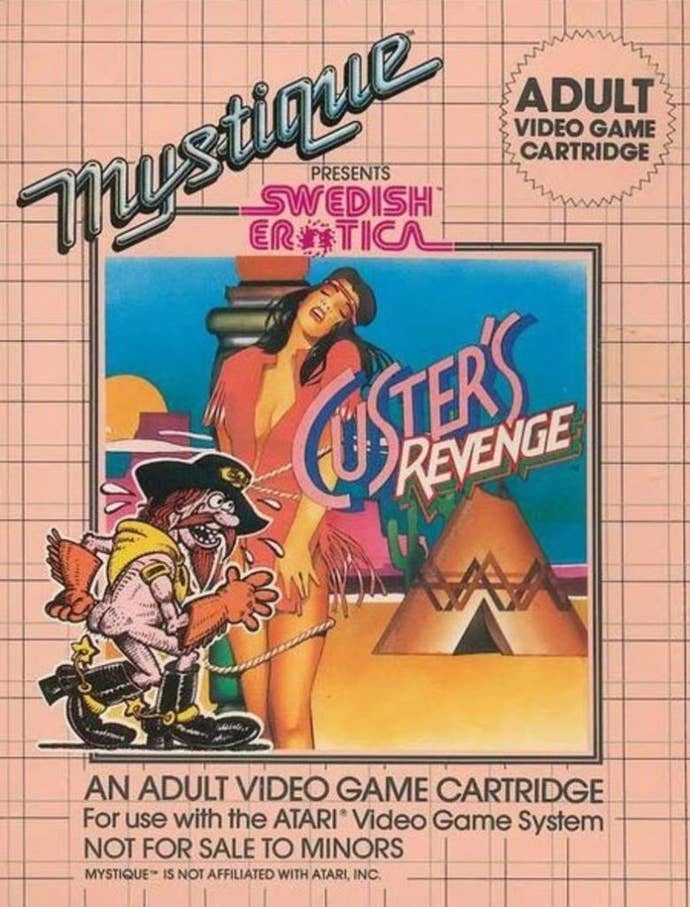

Custer’s Revenge is, so far as anyone can tell, the first depiction of American Indians in a video game. It is also still considered to be one of the most offensive games ever released.

In Custer's Revenge, the only goal is to repeatedly rape a captive Native woman while dodging arrows (presumably fired by other Natives). It’s easy to feel like the game is a relic of a bygone era of cultural insensitivity and that something like that wouldn’t be released today; but sadly, that’s not quite true. In 2008, a Brazilian team of students remade the quite literal rape simulator, this time with updated visuals. It’s still available to download, and there are Let’s Plays posted this year.

For some, this is a joke. For some, it can be played off as a funny thing that they’ll never have to see or deal with directly. For Native women? Things are different. According to the Department of Justice, American Indians are 2.5 times more likely to experience sexual assault than any other race or ethnicity, with more than one in three Native women reporting rape during her lifetime. I’d be remiss to conflate a 32-year old game with crimes committed by people who almost certainly haven’t played it. What is does do, however, is show how common it is for natives to be treated as less than individuals.

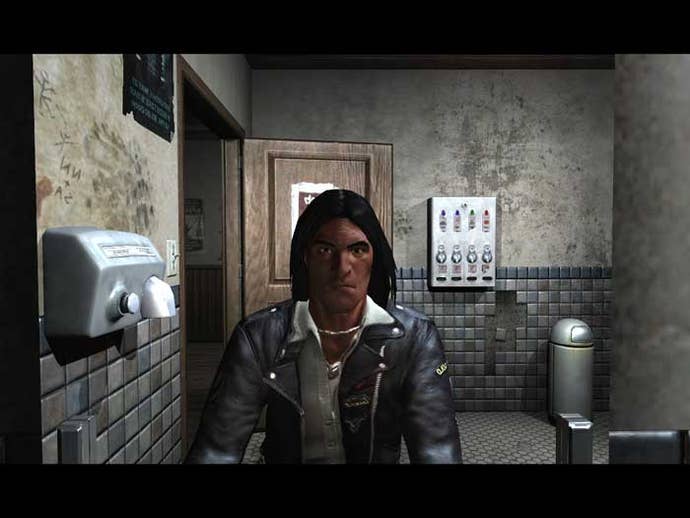

Pop culture often considers every tribe, every Native to be just one large group of homogenous people, and that’s become one of the most unfortunate and broadly limiting stereotypes of Natives. If you take a moment to think of every Native in games, you might be able to come up with a list of five or so. Tommy from Prey, the unnamed woman in Custer’s Revenge, the dude from Turok, Vulcan Raven, and Humba Wumba are the only ones that come to mind. With the exception of Tommy, who is Cherokee, the tribal identity of these people aren’t clearly established. Tribal backgrounds, religious affiliation and beliefs are as diverse as you would expect people spread out over whole continents to be, but its rare to see individuality or tribal identity respected. Typically, they are presented as little more than “the Native,” where their traits are reduced to barest stereotypes. Spiritual warriors, mystics and victims are the only roles available.

If you don’t fit into one of those boxes, you don’t get hit with the “Native” label. John Romero, one of the people behind the iconic early 90s FPS Doom is just one example. Speaking to him for this piece, he admitted that no had ever “highlighted or mentioned” his Native or Mexican heritage in any interviews. “It’s strange but I feel that I became white to everyone when I attained success. I have no explanation of it, but I feel that is what happened. I still have people ask me if Romero is an Italian name.”

That kind of white-washing is common in media and games in particular. In the most recent Turok, the Native protagonist is an ex-convict who connects with his heritage through a white superior officer. The implication there being that the actual Native isn’t Native enough and needs to be put into his proper role by a white man. Again, for most players these stories might come off as little more than oddity, but it reflects a real struggle in Native communities for proper and equal treatment.

If you’re a Native citizen of the United States, you’ve probably had to deal with the Bureau of Indian Affairs at one point or another. The organization is responsible for ensuring treaties with tribes are appropriately respected, and keeps track of the blood quantum of Natives. To be officially recognized as part of most tribes, you need a Certified Degree of Indian Blood or CDIB, and those are all administered by the BIA. Overseeing all of the that is the… Department of the Interior. The same association that maintains national parks. The fact that the United States has a Department of Human Services and that the BIA isn’t a part of that says more than enough. Given that the U.S. Government is primarily white, it also sends the message that even today, Natives don’t deserve to govern or define themselves. They must be recognized, classified, and assigned Indian-ness by an external source. That’s a very real part of the Native experience, but the minutiae of the mundane aren’t seen as part of the Indian experience because they don’t fit the stereotypes. Those familiar with blood quanta often equate to a form of steady, legal genocide. A system which over many generations, is intended to bring about the complete extinction of Natives.

"It’s strange but I feel that I became white to everyone when I attained success. I have no explanation of it, but I feel that is what happened. I still have people ask me if Romero is an Italian name." - John Romero

In an effort to address some of these issues, Native developers have begun creating their own games, realizing that the traditional game development cycle probably won’t make games about them or their struggles for a long time. Blood Quantum is the first game that tries to tackle these issues. It’s still in production, but tries to teach others about the real-world effects of trying to measure exact lineages to establish tribal identity. Project lead Renee Nejo said that she wanted to see something, anything that addressed who she was.

“When I was young, and we were starting to learn about manifest destiny in school, I couldn't wait... I felt like my little heart had a lot to offer to the conversation. But when It came time to read in class, that's really all we did. There was no discussion. No interaction. My short window to talk about what I thought made me special had closed… This is what set the tone for me with regard to my identity: ‘nobody cares’.”

Silence is a common theme in speaking to Natives of all kinds. They’ve been either forced into silence or simply told that no one cares about their struggle. It’s dehumanizing on a level that is hard for even the people who have lived it to really understand.

Manuel Marcano, known as Hurakan to his tribe, is a Taino developer who has worked on several big-budget titles like The Darkness and Bioshock in addition to the forthcoming Treachery in Beatdown City, and has since moved into the independent space. When I asked him why, a big part of his response was the prejudice he and other Natives still openly face. “I've been called stuff ranging from Geronimo to Tonto,” he lamented. “And of course, there was all the millions of times someone asked me if I wanted to have a powwow. Now add the fact that I was raised an omnisexual and I don't even have a personal gender identity, you can likely imagine there was other kinds of issues that could come up." These stories, much like Custer’s Revenge, aren’t relics of the past but a disturbing and painful part of the present for those that must face them every day.

Part of that problem almost certainly stems from the extreme rarity of Natives in game development. As of 2011, the International Game Developer’s Association only had 41 indigenous developers out of 6,438 responded to the survey, or a little over one-half of one percent. While there’s certainly far fewer Natives around today than most other ethnicities, that still means that Natives are less than half as common as they should be if game developers were representative of the general population. Women and other people of color face the same kinds of disparities, but the solutions for each group have to be appropriate for their cultural context. For Natives that means addressing extreme poverty and a lack of opportunity head-on.

“Can we expect a kid on a rez with no internet access to upload a game for Ludum Dare?” Hurakan said, referencing the competitive game jam series. “Can we expect a group of Natives who can't afford new cloths or food to bring a $500 laptop to Molyjam?”

Bringing in Native perspectives, he says is important, but we won’t see that if we don’t deal with poverty, with the lack of access to resources. “Most of my games don't have experience points which removes the need to grind, which in turn stops rewarding random violence. In one of my projects the player is severely penalized if they kill anything. Sustainability is another theme I work with. Most games are inherently about conquest or progression. My games focus on building communities and establishing lasting settlements.”

John Romero echoed those sentiments. “Don’t ever hide your identity. Diversity in games is a great thing and can only help the industry by bringing different culture and experiences to game design. I have no idea how many Natives are in game development because it seems like more of them are ‘coming out’ on a weekly basis.”

Many Natives including Hurakan have at one point or another, pretended to be someone else. “When I was younger I really played up being from Puerto Rico. People would perceive me as a Spanish speaking, super macho Hispanic. I was ‘in the closet’ about being from a tribe because I was surrounded by colonized people and because a person from the Caribbean is held to that stereotype. Seeing other people from tribal backgrounds did not cause me to ‘come out’, but it did make me feel that being myself was worthwhile.”

This past month we saw the release of a very special game. Never Alone is a game about Natives made (at least in part) by Natives. The game centers on a young Alaskan Native girl wandering the tundra, searching out the source of endless blizzards that have wreaked havoc on her village. The narration is in the Iñupiat tribe’s native language, and the art style based on traditional scrimshaw. It was made to give Native children hope and something modern that represented them and their culture.

Life for many Native children is dominated by statistics. Rates of suicide, dropout rates, alcoholism, substance abuse, and domestic violence are all high in Native communities. These are each complex problems requiring complex solutions, but with the rising prevalence of video games, giving children hope, teaching them about their language and their culture has never been more important.

To that end, some tribes have been in partnership with tech companies and game developers to work on these kind of projects. The Hoopa Valley Tribe even has working games made with Microsoft’s Project Spark that aim to teach children more of the language. Others like Elizabeth LaPensee have been involved in the game development community and provided talks, videos, and educational resources to start cleaning up the presentation of Natives in gaming. These projects are still in their early stages, but they’re the first signs that the culture is changing.

“Millions of people play video games, and because of the interactivity it becomes an interesting way of allowing people to experience a culture that might seem alien to them. It's much easier to empathize with someone if you know something about them and interactivity can create that bond. With more Natives being in games, and making games we can educate others,” Hurakan said. “At the very least I hope people will stop asking if I know anything about peace pipes.”

While many will, no doubt, see Never Alone as just another in the burgeoning “art game” movement, for Natives in the games industry, though it is by far the biggest step in the right direction that’s ever been taken. It’s taken more than 30 years, but the hope and will is there to undo the damage of the past, and with more Native voices standing up and moving into development, maybe 30 years from now we’ll have put some of these pernicious stereotypes to bed for good.