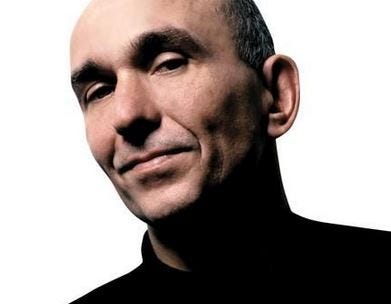

Molyneux: "I love this power. This is what I’ve always dreamt of" - interview

Peter Molyneux hypes analytics like he used to hype features in Fable. Will Godus be his greatest game years after release?

"Everybody is going to turn around and say, ‘Peter’s just overpromising’. I’m going to get into such trouble.”

At GDC last week, Peter Molyneux gave a session for attendees in which he showed a sort of hype video for the official, non-early access “launch” next month of his evolving new god game, Godus.

In it, Molyneux himself provided narration that explained the potential of Godus once player worlds become connected upon release: “Up to 50 million gods (players) will rule up to a trillion followers on a planet the size of Jupiter.”

“F**king hell,” Molyneux said to me after we watched that same video in a corner room, windows uncovered, on the 29th floor of a San Francisco hotel. I can’t say if Molyneux intended that location to be a metaphor - he’s often been described as a head-in-the-clouds kind of person - but it felt appropriate.

“Everybody is going to turn around and say, ‘Peter’s just overpromising’,” Molyneux went on. “I’m going to get into such trouble.”

It’s easy for us to go there when we remember that Godus’ Kickstarter campaign wasn’t a funding phenomenon like Broken Age or Mighty No. 9 or Pillars of Eternity, though it did reach its goal of £450,000. The idea that Godus will have 50 million regular players at any point seems like a pipe dream even with mobile versions playing a part.

But what’s more compelling about Godus from a theory standpoint right now may be Molyneux’s analytics scheme, which he idealised to me the same way he was prone to fantastically talk up any feature in a Fable game when he was at Lionhead. When Molyneux is speaking in a sweeping manner about the potential of Godus, he’s as much gushing over analytics as what the game actually is.

As is the norm these days, he and his studio 22cans have access to “terabytes” of data on how people play Godus, and they’re using that information to adjust the game as they go. Godus has already undergone an extreme alteration in its beta release, and the changes won’t stop after the game reaches its official release in April.

Acknowledging the creator’s ultimate conflict, in which nothing we make is ever truly completed but in theory we have to stop working on it at some point, Molyneux admits that when the game launches it’s not going to be exactly what he wants it to be, or as good as it could or should be.

“Will it be the greatest game that I’ve ever worked on a year afterwards? Well, maybe, because I can still be fiddling and tweaking and changing, and I can be looking at the raw data,” he explained. “It’s like going inside a brain and looking at the raw data that makes up people’s enjoyment of the game.”

"It’s like going inside a brain and looking at the raw data that makes up people’s enjoyment of the game.”

Molyneux decried the way he believes publishers use that sort of data to try to wring cash out of users in the short term, whereas he sees it as a way to figure out how to keep people engaged for longer. But it’s not so simple as just seeing the data and rolling with it; you’ve got to interpret it correctly. And as a designer, Molyneux says his job has shifted a bit within that context.

“You’re part curator,” Molyneux said. "You’re listening to all these different voices, and you’re cherry-picking which of those voices, whether it be from the community or the team or from press people, [are worth listening to].”

He described to me a hypothetical (I think) problem that demonstrates the types of dilemmas 22cans is dealing with and the trial-and-error approach it’s having to take when making changes in response to analytics

“Every single time we bring a dialogue up on the screen, we measure the amount of time it takes for someone to activate certain portions of the dialogue. And let’s just say in the top left-hand corner I’ve got a button which says ‘reassign’,” Molyneux told me. “And if I notice that people are bringing up this dialogue and closing it again but not hitting ‘reassign’ then that tells me something about the design of that very button. I then go to my office and say, ‘Look, people are not noticing this button.’ I make that change to that button, and now it really glows and sparkles, and I put that change out there, but they still don’t touch it. And then I start to realize… Hang on, the problem isn’t the graphical style of the button, the problem is with the motivation of the player. They’re not motivated to do that. They’re too busy doing something else.

“So I can wind the numbers back and say, ‘what were people doing just before they brought this dialogue up?’ They’re digging out a canyon, or they’re leashing some of their followers to honor a certain project. The timing of this button is wrong. If you’re fascinated with doing one thing and the game gets you to do something else when you’re not ready, that’s not a great game, that’s just a mistake. And this way I can measure that.”

The normal way of doing science - you know, in the real world - does involve a lot of interpretation and experimentation, and with Godus, Molyneux can do a lot of experimenting whenever he wants.

“If the game was in full launch now I could bring up my dashboard, and I could, say, just for fun, the two of us could change pretty much any aspect of the game for all people in south San Francisco,” he whimsied. “This is awesome power. I love this power. This is what I’ve always dreamt of.