Metroid Game By Game Reviews: Super Metroid

The third time's a charm.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

(Note: This week's Super Metroid review for Metroid Game By Game also doubles as our Super Metroid review for our ongoing SNES Classic Game By Game series!)

Debuting midway through 1994 on Super NES, Nintendo's Super Metroid — also listed as "Metroid III" in the introductory credits — represented a return to the original NES game in many ways. It marked the return of the series to consoles after its journey into portable monochromia. It saw the return of original designer Yoshio Sakamoto. Even the game setting walked it back, returning to the first game's setting: The space pirate stronghold planet of Zebes.

By no means does that mean Super Metroid existed as some sort of repudiation of Metroid II. On the contrary, the game begins with a brief sequence of exposition that sets the stage by building directly on Metroid II's finale. Many of the previous game's quality-of-life elements carry over into this third chapter: Save stations, resource recharge depots, large rooms, and handy power-ups including the Spring Ball and Plasma Beam. Nevertheless, much as with this game's 16-bit cousin The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, Nintendo consciously circled back around to the first game of the trilogy and applied more than half a decade of technological improvements and game design experience to the framework that had kicked off the franchise. And, as with A Link to the Past, this refine-and-expand approach resulted in a genre-defining work whose design principles continue to define gaming.

Super Metroid's creators did an extraordinary job navigating the very narrow line between inspired reiteration and insipid rehash. A sizable chunk of Super Metroid's otherworldly underground labyrinth comes directly from the NES game. By 1994, we'd seen the dangers inherent in treading creative waters in video games: Formerly masterful franchises like Mega Man and King's Quest had grown incredibly stale by playing it safe. Super Metroid may have reused material, but it certainly didn't play things safe. Instead, it harnessed the familiarity of its setting in the same way that Konami used the first stage of the original Castlevania in that game's many sequels: Revisiting a known location to contextualize and define each new work.

Castlevania had never reprised the first game quite so dramatically as we saw in Super Metroid's take on the corridors of its NES predecessor, though. After a brief introduction that brilliantly takes Samus Aran — and players — through the devastated bio lab seen on the title screen (minus a key difference: The baby metroid has gone missing by the time you reach the space colony), you arrive on Zebes. What you initially find is simply the ruins left in the wake of your first mission to the planet. You infiltrate the remains of the old pirate base through the tall vertical shaft through which you escaped the time bomb activated after you defeated Mother Brain, pass through the rubble of the Mother Brain's lair itself, and make your way to the iconic platform where the very first Metroid quest kicked off.

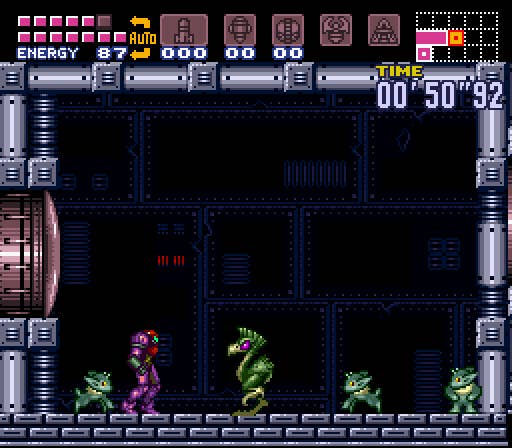

Throughout all of this, the only things you encounter are gloomy ambient sounds and what appears to be some sort of surveillance system. There are no enemies to fight, no hazards to avoid, just murky corridors and disused door and elevator mechanisms. However, once you collect your first item — the Morph Ball that allows Samus to curl up and duck into narrow spaces — the space pirate fortress explodes with activity. The minions of the Mother Brain clearly knew you would be chasing their boss Ridley back to Zebes and planted a trap accordingly, using Samus's (and the player's) compulsion to collect helpful items against them. It's a surprising twist, turning the series' chain of skill progression against the player, and the idea pops up a few times throughout the game: Sometimes, when you least expect it, the birdlike statues that enshrine item pickups will come after you for plucking away their prizes.

Super Metroid revels in subverting the player's assumptions like this, in putting unexpected spin on what had come before. Plummet through one of the false floors that littered the original NES game's labyrinths and you once again have to deal with the chore of working your way back up to the critical path... but this time, friendly local critters will offer handy diegetic tips to unlock Samus's hidden skills, such as wall-jumping and rocket jumps. You'll encounter a fake version of Mother Brain enforcer Kraid, as in the first game... but this time, the real Kraid turns out to be a towering monstrosity too enormous to fit onto a single screen. You catch a shocking, unnerving glimpse of a metroid while traveling through a conduit in underwater zone Maridia, long before the showdown with Mother Brain... but it turns out to be a failed clone of the space parasite. And once you do encounter metroids (precisely where veterans of the original game would expect to come across them), you don't expect the terrifying new twist that gives the game its title: The eponymous super metroid, a creature altogether different from the lifecycle variants of Metroid II.

Ultimately, though, Super Metroid's most important exploration of the original NES game comes in the way it refines the exploratory structure of the earlier work. Metroid's designers incorporated some skill-based gating to its world, which gave the open-ended adventure a certain degree of mandatory progression while encouraging players to press ahead until they hit a sticking point and had to backtrack in search of the ability needed to advance. You've found the missiles along the path to the fiery Norfair zone? Great, but you won't make it far in Norfair until you acquire the bombs back in upper Brinstar, where you came from in the first place — but of course you need missiles to open the door to the room containing the bombs.

Super Metroid leans into this concept and turns the revamped, expanded Zebesian fortress into a complex puzzle box of interlocking gates and keys. The overall structure of the game requires constant exploration and acquisition in order to advance. Importantly, though, it holds true to a fundamental principle of the original Metroid: There are no literal keys in play here. You "unlock" doors by gaining new powers for Samus. While Super Metroid does introduce a status and inventory screen to the mix, it never becomes Zelda-like in terms to the need to shuffle between tools. You swap between a limited selection of weapon-tools with the Select button — missiles, super missiles, grappling hook, X-ray beam — with the inventory screen reserved strictly to make use of reserve energy tanks in a pinch, or to activate and deactivate certain mutually exclusive weapons (finally, no more wasting time by replacing your wave beam with the ice beam before heading into the metroid-ridden final zone).

Super Metroid's dual-purpose power-ups — they're weapons and tools — redefined the concept of efficient game design. As Samus becomes stronger, she can access new areas, where she finds her advanced skills newly put to the test. Super bombs allow you to wipe out all enemies on screen, and they also have the ability to open otherwise indestructible yellow doors... and on top of that, a well-placed super bomb can also reveal all manner of hidden passages built into the walls. Super missiles don't simply pack a punch and open green doors; the power of their impact shakes the room and can knock enemies off the walls and ceiling. No skill in Super Metroid has been added frivolously, and exploring their undocumented capabilities is half the fun.

The game makes a brilliant effort to teach players the value of their newfound acquisitions. Most power-ups are situated so that you can't make your way back to the critical path after acquiring them unless you make use of that new skill. You can only escape the room containing the space jump by mastering the timing of its infinite jump chains. You can only leave the ice beam's room by using the new gun option to freeze enemies leaping from the lava, turning them into tiny platforms that will allow you to roll through a narrow exit halfway up the wall.

Super Metroid rarely becomes challenging in the traditional sense. A handful of encounters put up a fight — the two golden space pirates pose a greater threat than any single boss in the game — but the point of this quest isn't to test your physical mettle. Plenty of ROM hackers have created variants on Super Metroid that demand pixel-perfect play; yet with all due respect to their hard work, those efforts completely miss the spirit of Super Metroid. This game asks you to play at a more leisurely pace, to become lost in its labyrinth, to work your way through its mysteries one at a time. Raw dexterity doesn't really factor in.

The concept clearly has merit, given how many developers have copied Super Metroid's design and structure almost verbatim. It took a few years for everyone else to catch on. Only a handful of games worked like Super Metroid in the decade following its release, but once the indie game revolution kicked into gear, Super Metroid became a template for dozens upon dozens of budding designers. Pro creators have done their share of lifting as well; would Dark Souls or Batman: Arkham Asylum be half as beloved if they didn't adapt the flow of Super Metroid into immersive, 3D spaces?

Much of what Super Metroid introduced to the medium seems to have been accidental genius. By that I don't mean Sakamoto and his team stumbled onto good ideas through dumb luck; a game as drenched in tiny details as Super Metroid clearly didn't happen by mistake. Rather, I simply mean that the devs invented elements for the sake of making Super Metroid better and, in the process, came up with game design concepts that worked just as brilliantly in (and soon trickled over to) other games. The auto-map improved greatly on the one seen in A Link to the Past, and its format became a universal standard once Castlevania: Symphony of the Night canonized it. Meanwhile, Super Metroid's ending screen expanded the original Metroid's concept of giving players different images of Samus based on performance to include a numeric breakdown of their speed and thoroughness. In the process, Super Metroid essentially created speedrunning.

If there's a single reason to dislike Super Metroid, it's that the game's sheer immensity and excellence have cast an impossible shadow over the rest of the franchise. How do you improve on perfection? Nintendo has given it a shot many times over, but no follow-up to Super Metroid has had both the impact and influence of the series' Super NES outing. There really was brilliance lurking in the 8-bit heart of the original Metroid; it just took a few attempts to do it justice.

ConclusionSuper Metroid didn't simply lay down the ideal design for Metroid games, it created a template that countless other developers have imitated across innumerable franchises (sometimes to-the-letter). Add to that a preposterous number of loving subtleties and details, an incredible sense atmosphere, and a story that manages to be gripping despite its pantomimed nature and you have a true, timeless classic. It may not be a flawless game, yet somehow... it's still perfect.