Metroid Game By Game Reviews: Metroid

Nintendo's classic sci-fi adventure can be a tough sell today, but it redefined action games.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This is the first entry in a series that will review every Metroid game to date. Our first entry: The original Metroid for the NES, the game that started it all.

The original Metroid debuted in Japan late in 1986, and about a year later in the U.S. It arrived during a period of transition for console gaming. The NES hardware had been around for three years by the time Metroid arrived (its Japanese version, the Famicom, launched in July 1983), and the hardware had begun to show its age. Around the same time Metroid hit shelves, SEGA had shipped its Out Run hardware, a stunning racer featuring gorgeous "Super Scaler" graphics and a melodic FM synthesis soundtrack.

Nintendo's knew its home hardware couldn't compete with current arcade tech on equal terms. The company and its third-party partners began shifting away from the early days of NES and Famicom software, which had largely consisted of simple, arcade-style experiences. A key element of this new design strategy was the Famicom Disk System add-on, which greatly increased the storage capacity available for game data while enabling limited rewritable information, such as save files. The Legend of Zelda had been the Disk System's proof of concept: A vast adventure, inspired by role-playing games, in which players could save their progress and return to continue their exploration at any time. This would be the new standard for the NES: Bigger, more substantial games, too sprawling to be completed in a single sitting.

In the U.S., Metroid appeared in mid-1987, right as the console began to build momentum, and it spoke to the console's ultimate direction far better than the first wave of "Black Box" games from Nintendo. That was certainly the case for me: I got my NES shortly after Christmas 1987. (It would have been a little sooner, actually, but hardware shortages have been the natural state of Nintendo since the very beginning. My town was sold out of NES consoles entirely for months, and we didn't get ahold of one until my father happened to travel for a family funeral and spotted on in a department store 1500 miles from home.) A couple of months later, I bought Metroid as my first non-packed-in game for the console. I was drawn in by my friends' enthusiasm for the game along with its intriguing box, but I had no conception of how huge and challenging the game would ultimately prove to be. And I have little doubt that it shaped my tastes, filling me with a profound love for open-ended action-adventure games.

In America, Nintendo shipped Metroid in a package that looked very much like its initial Black Box titles for NES, but with a few differences. The black had become silver, and it wore the badge of a new software "series": The Password Paks. Inside, Metroid's manual boasted full-color printing throughout a booklet many times the length of, say, the Balloon Fight or Super Mario Bros. instruction guides. The Metroid manual featured an elaborate story about galactic politics and an evil villain called Mother Brain, all as setup for a complicated, RPG-inspired, enigmatic gem of an action game.

In hindsight, Metroid does seem like something of an oddity in the Nintendo catalog. Here's a game about a space bounty hunter battling his (actually her) way through an underground labyrinth trying to save the galaxy from marauding parasites capable of devouring a person's life essence in a matter of seconds. Its environments are wreathed in darkness; its objectives frequently feel unclear. That lines up pretty strangely next to the candy-colored whimsy of Splatoon or Super Mario Odyssey, doesn't it?

Viewed from a different angle, however, Metroid couldn't possibly be more Nintendo-like. Maybe its hard-boiled sci-fi combat and oppressive environments represent the company stepping outside its cartoon comfort zone. In terms of play mechanics and game design, however, Metroid feels like Nintendo at its most Nintendo-esque.

The driving principle that powers the original Metroid draws on the company's ultimate overriding design philosophy: Never overcomplicate things. Make a game just as complex as it needs to be, and not an iota more. In Metroid's case, this strict minimalism resulted in a game that, in design terms, falls midway between Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda.

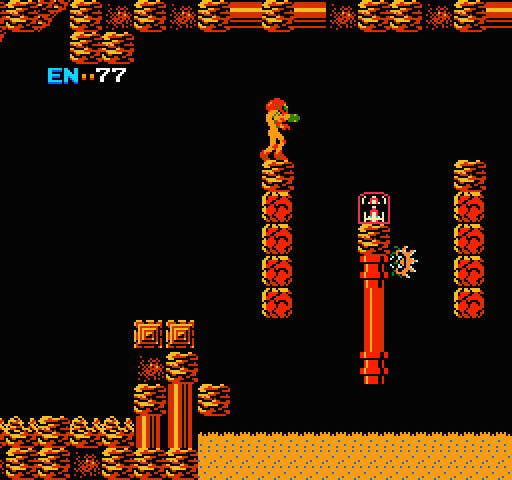

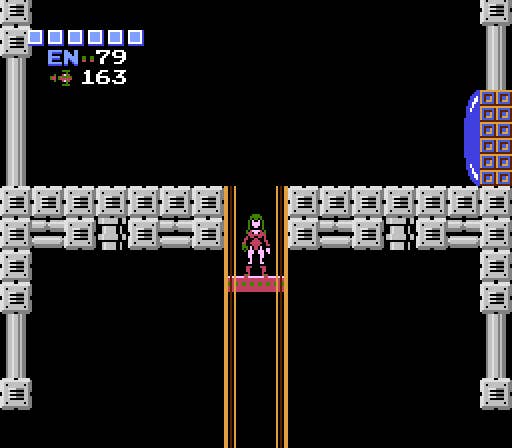

It's a platform action game (like Mario) that consists of exploring dungeon-like mazes with the aid of tools and permanent power-ups (like Zelda). Metroid has a far more intricate design than Mario's strictly linear stages, as players wander through a series of convoluted, interconnected regions with no fixed end goals along the way. Metroid's world contains hidden secrets similar to Mario's invisible coin blocks and spring boards into the sky, but these obscure details do more than simply provide a score bonus: You need to uncover them in order to progress.

Structurally, Metroid more closely resembles Zelda. The starting zone of the underground space pirate fortress, Brinstar, works a lot like Zelda's overworld: It links together multiple other regions that contain the player's primary objectives. The passage to the final zone even uses a gating technique similar to the one at the entrance to Zelda's Death Mountain. You can make your way to the entrance to the final area quite easily from the outset of the journey, but until you've fulfilled a mandatory objective (in this case, defeating mini-bosses Kraid and Ridley), you can't actually cross the entrance threshold into the endgame challenge.

Also as in Zelda, Metroid builds a sort of parallel sub-quest of empowerment into the adventure. While protagonist Samus Aran works toward an ultimate goal of stopping the Mother Brain and her minions, she also hunts for better equipment. These boosts improve her chances of survival while literally unlocking doors and opening pathways forward. Samus's upgrades provide a means to the end of defeating the bad guys, but in many ways they're also an end unto themselves. The weak, fragile Samus you control at the beginning may look like the same bounty hunter who ultimately shatters Mother Brain's core containment device, but in terms of raw capabilities, they're practically two different characters.

Metroid diverges from Zelda's design in a single, critical way: It lacks a sub-screen. Zelda's Link acquires a prodigious amount of equipment while making his way through Hyrule - so much that players constantly need to switch over to a secondary screen in order to toggle between tools and weapons, chart the progress of their quest for the Triforce, and keep track of their location in the current dungeon. Yet while Samus has to manage nearly as many play factors as Link throughout her own quest, she does so in a more seamless fashion. There's no in-game menu screen, no way to track your progress. If you want to map the game, you have to do it by hand, on graph paper. There's not even any indication of your current maximum capacity for expendable missiles happens to be; the only way to be sure is to keep collecting missile refills until your current tally stops incrementing.

It's a stark, sometimes bewildering approach to a game this complex, and it makes Metroid feel like a throwback even as it redefines platform action games. If Zelda pushed the role-playing game genre forward by streamlining its concepts and providing players a quick, efficient, information-rich interface at all times, Metroid presents the action game as an early PC RPG. There are no niceties here, no hand-holding for the player. It drops players into a dense, obtuse maze and expects them to sort through it all on their own. It's Wizardry as a sci-fi shooter.

The game can be painfully difficult for a newcomer to parse today, with its lack of an automap and its reliance on critical pathways exposed only by bombing unremarkable bits of wall or floor. 30 years of game interface improvements and quality-of-life refinements (many innovated by Metroid's own sequels) have led players to expect certain niceties this game lacks. By modern standards, Metroid truly feels like a relic packed with annoying design choices. From the way you begin each session with a mere 30 points of health (even if you've maxed out your capacity at 699!) to the need to bomb every surface in sight in order to uncover essential passages, the game seems to delight in confounding players at every turn.

Yet Metroid's opacity doesn't entirely represent a failure of design; in many ways, it's deliberate. The lack of an inventory management option directly shaped the nature of Samus's power-ups. There's no way to toggle equipment or fuss with tools to clear a scenario; once you collect a weapon or upgrade, it becomes a permanent part of Samus's arsenal. (The one exception: Samus's primary gun, which can be either the Wave Beam or the Ice Beam, but not both.) Every capability Samus has earned is always available right at the player's fingertips: High jumps, bomb-rolls, destructive spinning jump attacks, long-range projectiles, and more, all available with the press of two face buttons (with the Select key as a missile toggle).

Metroid's single greatest contribution to gaming could be this, the concept of a self-contained, self-reliant, ever more powerful protagonist. Samus is explorer, weapon, and key all at once. Her power-ups have permanence, unlike those of her action game forebears. Pac-Man's energizers wore off after a few seconds. Mario would lose his Fire Flower from bumping into a bad guy. Samus's powers are forever. Her enhancements make her more durable, allowing her to go up against ever more dangerous foes, and they also give her the ability to reach the areas where those foes reside in the first place. High jump boots and ice beams don't simply come in handy in combat; they also put new areas within the player's reach.

Exploratory platformers and action RPGs would become deeper, friendlier, and more refined through the years, and most of them have evolved out of Metroid's design. Nintendo stripped the whole thing down to its basics here, creating a framework for others to build on. So much about gaming begins right here, with the enigmatic Samus Aran.

ConclusionYes, the original Metroid seems a bit primitive by contemporary standards. Such is ever the fate of pioneering works. A much improved remake is available in the form of Zero Mission, but the original game is worth investigating… if only to see how far we've come.