Metatext: Separating the Player from the Character

Ever get the feeling your video games are talking to you? You may not be crazy after all....

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In playing through Animal Crossing: New Leaf, I've had a few "aha!" moments. For example, I've caught some rare animals that always eluded me in previous versions of the game, which made for a nice esteem-booster. And then, quite by accident, I stumbled across what sounds like an off-key rendition of Totaka's Song in my very own basement...

...I've even chilled out to the soundtrack when I'm not playing. But the most curious thing about New Leaf is the sense that the characters talking to my little playable avatar aren't really talking to him at all. Instead, I get the distinct impression that sometimes they're speaking to me.

I suppose this would normally be the point where I worry that I'm cracking up, but in this case I feel confident in my own sanity. While New Leaf, like every Animal Crossing, has a story limited to "You're the new kid in town, come enjoy our slice of capitalism" (this time with the added perk of being installed as mayor of your little village), it also incorporates a kind of metatextual narrative directed at the player.

Where your avatar is meant to be a newcomer, freshly inducted into the collectathon world of Animal Crossing, Nintendo also recognizes that many of its customers are returning players who have dabbled in this world before. And so, quietly, subtly, the game presents something akin to continuity, inasmuch as such a thing can exist in a series like this. Some instances are more obvious than others: For instance, you take over as mayor for Tortimer, the elderly turtle who ran the town in previous entries.

But Tortimer treats you as a newcomer and invariably speaks directly to your avatar. Other characters are less direct about the changes they entail, though. The notorious Tom Nook alludes to the fact that his role as real estate agent is something new, and formerly picaresque musician K.K. Slider makes an oblique reference to the fact that his new, permanent home marks a change of pace for him, too.

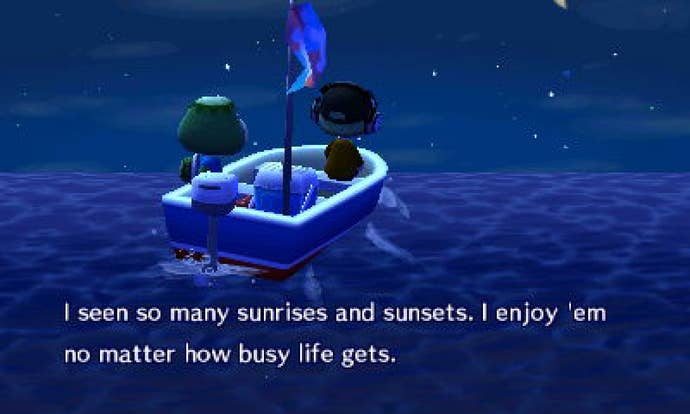

It isn't until you hop on the motorboat to the game's tropical island getaway that you'll start to notice the game talking past your little on-screen minion and speaking to you, the player. It's not direct, obvious, House of Cards-style fourth-wall-breaking; nothing so inelegant. But as the boat's pilot, Kap'n the Kappa, drives you out to your insular destination, he'll regale you with a few lines of a sea shanty, drop an odd spoken comment, and wrap up with the closing refrain of a tune unrelated to the first.

If you pay careful attention to Kap'n lyrics, you'll notice he's making remarks that wouldn't really mean much to a first-time player or, by extension, your fresh-faced protagonist. But for those of us who remember Kap'n from his appearance in the GameCube Animal Crossing, his lamentations on hair loss and musings on how having a daughter has changed his life speak to the years that have passed since we all first played Animal Crossing. Certainly I have a lot less hair on my head than I did in 2002, and my wife and I frequently discuss the prospect of having kids, so his ditties hit close to home. On top of that, when Kap'n does directly address my in-game avatar, it's with an almost paternalistic tone. The result is a surreal simpatico between myself and Kap'n, as the game (or rather, its writers) feel my own pains of getting older as we watch some ageless whippersnapper run around retracing the steps I took a decade ago and surpassing those efforts.

Breaking down the barrier between game and gamer is hardly a new idea. On the contrary, it seems to be all the rage these days. BioShock's big twist was to poke holes in the illusion of player agency in video game, sharply and brutally reminding players that while they control the hero, the game ultimately calls the shots and often wrests away that control at the creators' whim. Bungie's Marathon explored similar themes years before that, albeit in a less graphic manner. Nier, Braid, and Shadow of the Colossus have each turned the story back around on the player, forcing them to question the morality of heir in-game actions -- or rather, their unquestioning acceptance of the limited path to resolution that the games provide.

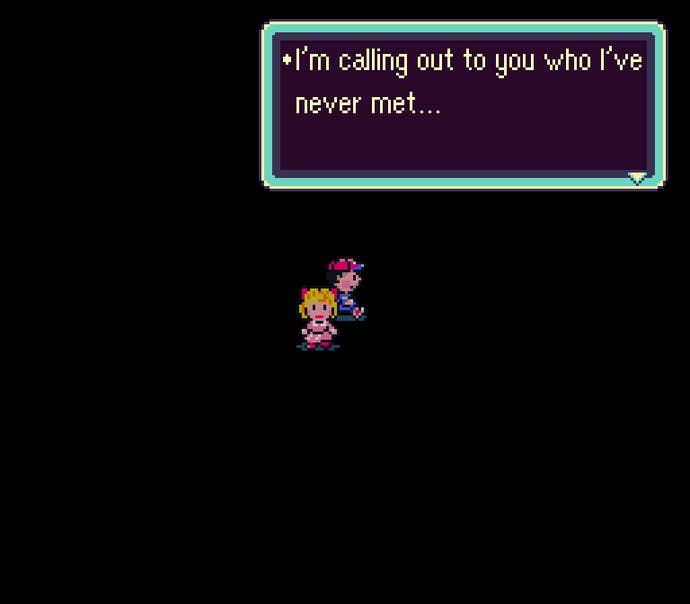

While none of these games directly call out the player, they nevertheless break down the illusion of immersion and remind players of both the potential and limitations of the medium. But they have nothing on Nintendo's cult classic EarthBound. Written by famous essayist Shigesato Itoi rather than someone whose entire career revolved around games, EarthBound constantly takes playful pokes at the medium, making jokes about illogical but commonly accepted video game standards. Still, the fourth wall comes crashing down at the game's climax, when the protagonists stop and turn to face the player. Suddenly, the personal information you entered at the very beginning of the game and promptly forgot about comes into play as the heroes and heroines beg you for your help defeating an otherworldly force of unimaginable power and malice.

If you're not expecting it, this turn of events is quite stunning. Taken in the context of the final showdown with the mighty Giygas, set in an unsettling, surreal dreamscape, it feels almost like the game itself is breaking down. It's perhaps the most clever and powerful moment in a clever and powerful game.

Still, my favorite barrier-busting moment in a game comes at the end of the generally overlooked DS adventure/RPG Contact. Having traveled through half a dozen worlds with a strange scientist from an odd, pixelated alien world, the hero delivers the last of the MacGuffins the professor needed to repair his traveling laboratory -- at which point the scientist promptly swipes it and takes off, leaving the protagonist feeling mistreated and abused. In rage, he lashes out at the only person he can think to blame for his unhappiness: You, the player.

Cursing your name, the protagonist threatens and insults you. But he's ultimately powerless against someone who has literally controlled his actions throughout the adventure; he fumes and rages impotently until you put him in his place by tapping him with the stylus. It's a weird and wonderful moment in which the abstract interface tool you've used to guide your tiny hero through his adventure (telling him where to focus his weapons and attacks) becomes a weapon in and of itself.

These moments remain profound for their scarcity. If every game pulled these tricks, they'd become as clichéd as aiming down iron sights or performing bloody quick-time murder maneuvers. Still, I have no doubt that the examples I've cited above only scratch the surface on gaming's metatextual moments. What are your favorites? Blow my mind.