Like A Dragon Gaiden is the perfect conclusion to a story that never ends

Kazuma Kiryu’s metamorphosis is a heart-wrenching reminder that, for better or worse, life goes on.

Content Warning: Discussion of themes relating to suicide and spoilers for Like a Dragon: Gaiden

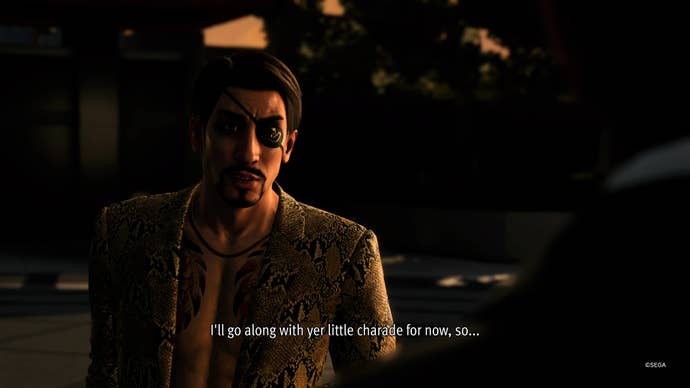

There’s a gun being pointed towards the back of his head, but he says it’s fine.

“I’ve been dead for three years now,” he laments, “I won’t haunt you from beyond the grave.” Just like all of the others, the man holding the gun this time can’t do it. “Always so quick to sacrifice yourself for others,” he replies to the tortured soul formerly known as Kazuma Kiryu, “How has that attitude not gotten you killed yet?”

It’s a valid question for Hanawa to ask, but he’s already shown that he knows the answer. The only person that could ever have killed Kazuma Kiryu is Kazuma Kiryu. In Like A Dragon Gaiden, that step’s already been taken, and - heartbreakingly - at first, it seems like it isn’t enough.

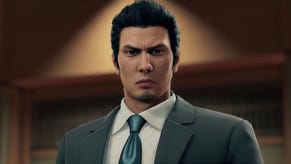

The choice the Dragon of Dojima made at the end of Yakuza 6 defines the being whose body you find yourself trapped in throughout RGG Studio’s most recent work in the Yakuza series. Everything the man now labelled Joryu does involves grappling to reshape his sense of self in order to fit what he now is and attempt to redefine it in situations when the differences prove impossible to reconcile.

He’s faked his death rather than having turned into a hideous bug (as happened to Gregor Samsa, the unfortunate protagonist of Franz Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis), but the two situations are strikingly similar. Prior to their transformations, both men’s lives are defined by that nasty little question that squats at the back of all of our minds: ‘Why am I doing this?’.

Kiryu is buried neck-deep in a vicious cycle of physical and psychological torture. He feels like can’t stop putting those he loves at risk and his own health on the line to protect the yakuza clan his adoptive family once stood for and, more importantly, the way of life it symbolises. Men like Kiryu have to have somewhere to go to make something of themselves, and as things stand, that can’t happen without those orphans in Okinawa struggling to sleep at night.

Samsa’s sick of his life as an overworked salesman, but he’s had to push on with it because his parents are in debt to his tyrannical boss. Something bigger is at stake, and so people and their feelings must be set aside.

To a degree, that’s what all of us have to do on a daily basis, but in these two cases, things have kept bubbling up until something has snapped, but the circus of frustration doesn’t leave town. Now an agent for the soulless Daidoji Faction, Joryu is still being forced to put himself in harm’s way and being held hostage by the threat of violence against his family.

The gun Hanawa points at him isn’t what ends up keeping him in his cage after it’s demanded that he pick one up himself and kill the Watase family. It’s a reminder that the sword of Damocles hangs over the children of Morning Glory. Then, it’s through the organisation of a deal between the Watase’s Tsuruno and the Dadoji that Joryu ends up being roped into the plan to dissolve both the Tojo Clan and the Omi Alliance. Throughout the game he’s relegated to being an entity that’s used, traded, and talked about by the friends, allies, and enemies that surround him.

He’s always been seen by a lot of people as more of a force of nature or a piece on the chessboard of life, a thing to be sought out for gain, taken into account, or removed from the equation entirely, rather than a human being. Now, trapped in exile from those who care about him in that sense by the same bubble of anonymity that’s supposed to protect them, the process is complete. He’s a thing. An object with a label, a walking corpse in a bodybag with a toe-tag that bears a price where a name should be.

Despite his efforts to carry on as normal or at least find a way to minimise the harm his sudden transformation might have on those around him, Samsa also ends up as an inhuman entity. Something to be hidden, to be managed, to be minded by his family and a string of housekeepers. A useless ghost haunting his former bedroom, increasingly ignored as much as is possible by the outside world, once the initial morbid curiosity invoked by his situation begins to wane.

Increasingly, it seems like all both parties can do is watch how the world around them fares without them in it as they once were. At times, it seems like they feel as though they’re watching new episodes of a show they used to star in after their character was killed off or re-cast. Every scene is a scene without them in it, filmed on familiar sets where they once shuffled about, interacted with props, and delivered lines.

The wider plotlines being acted out are inseparably linked to each tale’s protagonist, but are also shrouded in a veil that divides Kiryu and Samsa from interacting with them without feeling like an alien. In Kiryu’s case, the Great Dissolution of the Tojo Clan and Omi Alliance by his long-time allies and protege is an idea that he hasn’t had any input in creating, even if he ends up helping it come to fruition - by performing a role they’ve planned out for him.

In the end, both are stories that I can’t help interpreting as exploring that dreaded question I think pretty much everyone’s found themselves thinking about at - however briefly - during the most difficult moments life throws at us.

What would the world - my world - look like if I wasn’t here?

The messages you can draw from both The Metamorphosis and Like A Dragon Gaiden are well worth taking the time to appreciate.

Kafka’s work ends with Gregor Samsa’s family - the formerly struggling people he put himself through years of self-sacrifice and toil to help - finally leaving the flat that his fate haunts and taking a trip out into the countryside. They realise that because of the changes they’ve made since the story began with Samsa’s famous metamorphosis, their lives are now brimming with “new dreams and good intentions”.

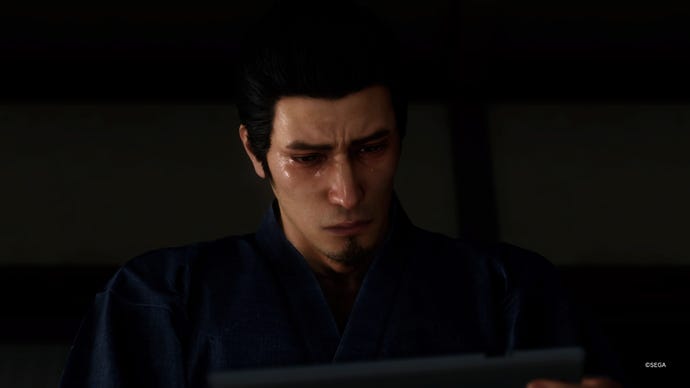

Meanwhile, in what quickly became Gaiden’s defining scene, Kiryu finally ends up getting to see those orphans in Okinawa he’s been unable to visit since he erased his own name. Via some video cameras planted by the Daidoji, he gets to watch them visit his grave. Then, Taichi and Ayako notice the camera and talk about what the kids’ lives have come to be like while Kiryu’s been absent.

Some have already secured jobs, some have dreams and goals they’re pursuing, most bear strong signs of Kiryu’s positive influence. Haruto can walk now.

The most important thing is that they’re all ok. Kiryu’s leaking tears turn into a deluge, because he realises the truth.

It’s natural to worry about how the people you care about are doing and where you fit into the constantly-shifting world that surrounds you on a daily basis. The most terrifying thing about life is the idea that it’ll always keep on going, with or without you.

At the same time, the most beautiful thing about life is that it’ll always keep on going.

With or without you.

Like a Dragon Gaiden is available on Game Pass now. Members of the service can also check out our list of best Game Pass games to see what else you can grab and play, at no extra cost, today.