Legend of Love: The Making of The Battle of Olympus

Infinity's Yukio Horimoto explains how his NES cult classic was a literal labor of love.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Originally published November 2015.

The term "cult classic" sounds nice, but it's really something of a double-edged sword. What it really means is that those familiar with that "cult classic" almost universally love it... the problem being that, ultimately, only a small number of people actually do know of it.

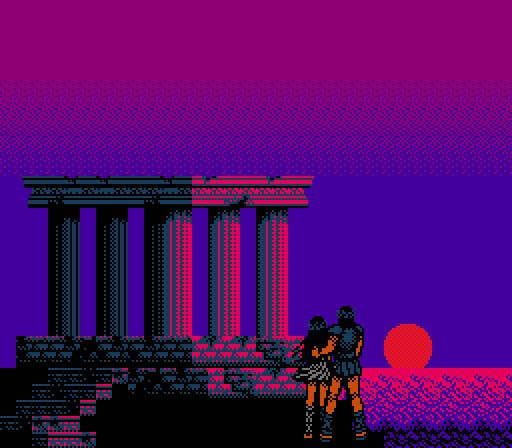

By that definition, The Battle of Olympus—a 1988 action role-playing game for the Nintendo Entertainment System—embodies the "cult classic" concept in every sense of the phrase. Avid NES fans hold the open-ended platforming adventure in high regard, but it remains largely unknown to the general gaming population... something that's been true of the game since its debut. But perhaps even more importantly, cult classics tend to be works that result from genuine passion, from a certain spark of inspiration that drives a creator. And this, too, describes The Battle of Olympus. Produced at a time when countless fly-by-night publishers were flooding the Japanese NES (called Family Computer, or Famicom, in Japan) market with quickly made and poorly designed software in order to cash in on the craze for the console as cynically as possible, The Battle of Olympus was a very personal, and very genuine, project for its creators.

Designed with enthusiasm and sincerity, boasting an ambitious scope, exploring an unconventional theme and setting for games, and crafted with impressive technical and artistic accomplishment, The Battle of Olympus should have been a smash hit in any just universe. Instead, it flopped, scuttling its creators' dreams of turning development studio Infinity into a source for original properties and fresh ideas. The company instead spent the following decade working on ventures it knew to be a sure thing: Converting American PC games to niche Japanese computers. Infinity filled an important and valuable niche to be sure, but its highly specific and decidedly one-way focus all but guaranteed that the company would be forever an unknown outside Japan.

Still, Yukio Horimoto—Infinity's president, and Battle of Olympus' programmer and co-designer—speaks with evident pride about the game, even nearly 30 years after its creation. "I have tell you my awesome story," he said with a laugh as we began to discuss Olympus' creation.

Olympus was Infinity's third game, but the young studio's first wholly original title. Their first project, Kieta Princess for Famicom Disk System, had been a contract project based around a popular "idol" actress at the time. That was followed by a PC conversion of a European tennis game for Amiga. Olympus, on the other hand, Horimoto and his small team designed from the ground up. He pitched the project to the publisher he had worked with on Infinity's previous creations, Imagineer, and got the green light.

"We shared the story concept with our client," says Horimoto. "The client liked the story, and he challenged us to create the game—so we made it."

As the title implies, The Battle of Olympus centered around Greek mythology. A loose retelling of the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, Olympus spanned the breadth of Ancient Greece, from Crete to Mt. Phthia and ultimately into the depths of Hades' underworld realm. While Greek lore wasn't entirely unheard of in NES games—Nintendo's Kid Icarus being the most prominent example—Olympus felt far more faithful to the classical source material than other takes on the setting... even if Eurydice did get the boot in favor of a girl named Helene.

That one name change aside, Olympus followed very much in the footsteps of the original myth—with a few video game twists, of course. Protagonist Orpheus traveled the land of Greece in search of mystical relics that would allow him to retrieve his abducted love from Hades' clutches, consulting with priests and gods themselves for advice on how a mere mortal could possibly hope to best a divine being.

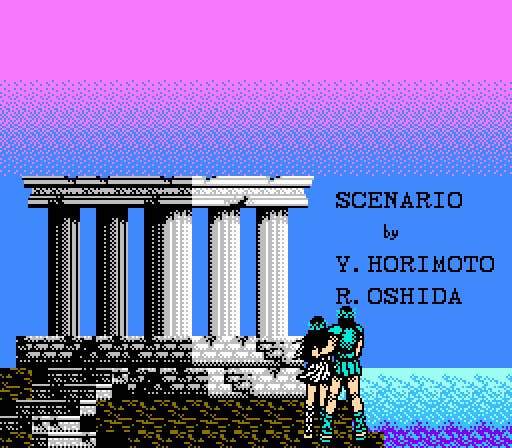

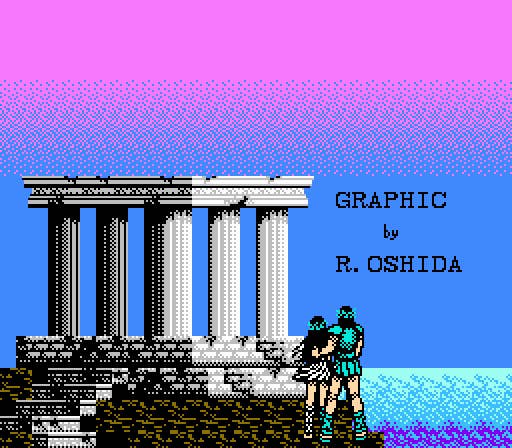

Fittingly, Olympus' Japanese subtitle was "Ai no Densetsu": The Legend of Love. That name fit the circumstances of the game's creation as much as it described the plot. Just as with Kieta Princess, Olympus was the work of a team of merely three people: Horimoto handled design and programming, Reiko Oshida worked on the graphics and story, and Kazuo Sawa composed the soundtrack. Creating a grand, non-linear, action RPG like Olympus was an impressive feat for such a tiny team working on a tight deadline (the production cycle was "maybe half year or so," says Horimoto), but the venture meant a great deal to the core team of Horimoto and Oshida: It was their first creation as a husband-wife team.

"While making our first game, I met [the woman who would become] my wife, and so… well, we got married, and she’s my wife," recalls Horimoto. "We fell in love and wanted to make our own game together, so we talked about the game concept for a long time. I like Greek myths and legends, so we decided to base our game on those legends." He admits, somewhat bashfully, that their romantic infatuation helped shape the direction of the story. "Given those circumstances," he says, "we talked about the game, and our mood influenced it."

In fact, the entire mythic theme turned out be a product of that part of their lives. Horimoto says he doesn't have any sort of lifelong fascination with Greek lore: "Around that time, I'd read some books [on the topic] that had interested me, and we felt that Greek legends would be a good theme for our game. We collected many books about Greece legends [for research]."

Somewhat similarly, the decision to build the plot around the tale of Orpheus emerged not from a particular enthusiasm for that specific story; rather, Horimoto and Oshida chose their protagonist based on the general theme of the game and the need to come up with an excuse to send Orpheus roaming all across the country.

"We drew a map and how he moved on the map," Horimoto says, "and so we need to set up his purpose. His lover's kidnapping made the base of a good story. Many Greek gods were in the story. Setting up the plot was very easy, not difficult at all.

"My wife's role was very important. In a lot of ways, she made it her own story, and I think the dramatic elements [such as the final showdown with Hades] — that's something my wife is good at."

Horimoto credits Infinity's ability to complete such an expansive, story-driven game complete with non-player characters, an inventory system, and multiple currencies and collectibles to the programming tools he developed. To play test games, developers had to write data from an NES development computer to an rewritable ROM format the console could recognize—typically a slow and arduous process. Infinity's custom NES tools reduced time spent waiting for a ROM to burn considerably.

"One thing I'm really proud of is that I made my own assembler," he says. "We had to write programs and then use an assembler to compile assembly language to machine code. While we were working on the game, I made my own custom assembler, because the existing tools were very slow. It was really stressful to create ROM images, and my assembler was, I think, about 10 times faster than others, so I could test my programs more frequently. Before that, when I needed to build a ROM image, it would take 10 minutes or more to write from the hard drive. With my system, it took maybe one minute or so. That was a very good experience."

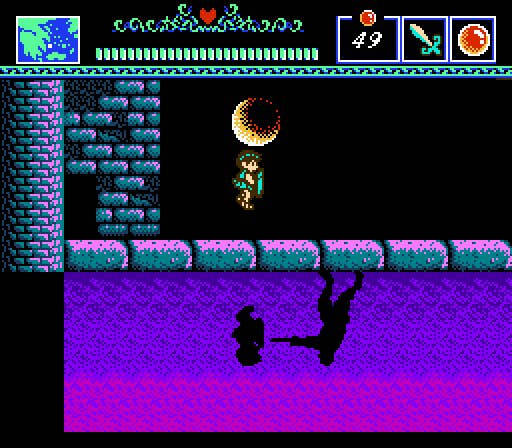

Another factor that probably helped speed development along was that the team had a direct inspiration to draw upon. Just as Oshida based Olympus' story on Greek myths, Horimoto patterned the game design largely after Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. No Battle of Olympus retrospective is complete without a tongue-wagging reference to its similarity to Nintendo's second Zelda adventure, but Horimoto says the similarity is no secret and no coincidence.

"Quite simply, Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda interested me. It inspired me to make a scrolling platform game. [I looked to Zelda II's] jumping system and walking system, and I imitated them. I wanted to make the same kind of game, and so many parts of the game, like the player's attacking motion, ducking motion, and jumping motion: They were all influenced by The Legend of Zelda."

Olympus isn't strictly a carbon copy of Nintendo's game, of course. It abandons the free-roaming RPG-like overworld map with its random encounters in favor of a simpler point-to-point map, which works greatly in its favor: The overall experience feels less fragmented and more focused than Zelda II. It also manages to be far less opaque and arbitrary in its quest design than its inspiration, presenting players with more clearly stated goals and avoiding shenanigans like forcing players to chop down an entire forest in search of a hidden town.

Even when the similarities are impossible to deny, Olympus attempts to mix things up. Perhaps most notably, it literally flips Zelda II's final battle upside-down: Just as Link had to fight his own shadow, Orpheus can initially only see Hades' shadow on the floor, from the light cast by a mystical artifact you need in order to complete the game. It's a perfect example of how Infinity looked to Zelda II for inspiration but nevertheless put interesting twists on mechanics and concepts that allowed Olympus to stand on its own.

Horimoto says the decision to pattern Olympus after Nintendo's hit was borne of genuine admiration. "Many people like Nintendo's games, and I've always liked them myself. The first [Zelda] was on the Famicom Disk System. I played many, many Disk System games, and the very first one was Legend of Zelda and the horizontal-scrolling Zelda II.

"Nintendo’s quality... they made the best games around those times, and I wanted to make a game of similar quality, too. I didn’t know if I would be able catch up with them, but I put my whole effort into the game. So did my wife. Her challenge was to make the most beautiful game graphics possible, and there's been a lot of praise for her work. All on such a small cartridge—only 16 colors! A very limited environment."

Despite the effort the tiny team poured into Olympus, it performed poorly once it went up for sale. By 1988, the Famicom market was in decline and crowded with games, making it difficult for original software to find an audience. Subsequently, Infinity resumed work on Western game ports, bringing classics like Doom and Populous to Japan, while a Brøderbund-published localization of Olympus found moderate success overseas. (The game evidently did well enough to merit a Europe-exclusive Game Boy conversion programmed by Radical Entertainment, which Horimoto had never heard of until I inquired about it.)

"For almost 20 years or more, I had forgotten all about The Battle of Olympus," says Horimoto. "It's only been recently that I've met people who knew about it." Despite the recent groundswell of fans nostalgic for his classic creation, though, he doesn't seem interested in revisiting it. Currently Infinity's focus is firmly fixed on surviving in the ever-shrinking Japanese market and branching out into overseas offices, which leaves little room for dwelling on the past. He wouldn't be averse to someone else taking up the cause of remaking the game, but he has no desire to be part of the process. "You make it," he says, chuckling.

He does feel, however, that any attempt to revisit Olympus would need massive rebalancing. "I made it too hard!" he laments. "I can’t finish it. When I was developing the game, of course, I finished several times, but now? It’s impossible, yeah. The final boss is awful!"