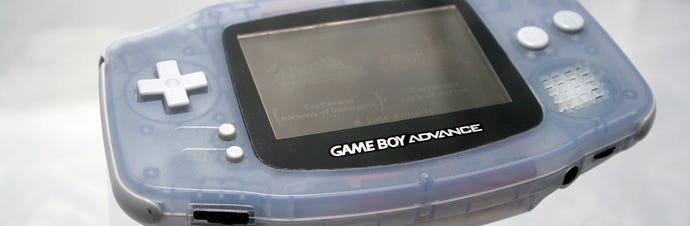

Last of the Line: Game Boy Advance Ended One Legacy as It Began Another

15 years after its debut, Nintendo's final single-screen handheld stands out as a herald of transition.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Nintendo's Game Boy Advance debuted 15 years ago this week in Japan: March 21, 2001. Like Nintendo's other system hailing from 2001, the GameCube, the GBA feels like an ill-fitting piece in Nintendo's history.

To be sure, GBA fared much better at retail, and in the hearts of gamers, than its TV console contemporary; all told, Nintendo managed to sell about four times as many GBAs as GameCubes. And for a certain generation of gamers, GBA lives in their memories as a foundational platform, the way the NES, PlayStation, and Genesis do for millions of older game enthusiasts. In fact, Game Boy Advance sits comfortably as one of the top 10 best-selling consoles of all time, and it initially placed in the top five before being edged out (just barely) by PlayStation Portable, Xbox 360, and PlayStation 3 years after its 2008 retirement.

Despite its successes, though, the GBA can't help but be overshadowed by the even more massive hits that preceded and followed it. The GBA failed to outperform its 8-bit predecessor (the Game Boy family), and its successor (the Nintendo DS line) outshone them both. Combined with its brief life — the DS was launched a mere three and a half years into GBA's run — and a library that often felt like leftovers from the Super NES era, the GBA sometimes struggles for proper recognition.

It was a fine system, though. Flawed, yes, but a worthy conclusion to the Game Boy line. At the same time, GBA helped usher in some important features that would come to define the future of portable gaming. In fact, across GBA's three major iterations, you can see Nintendo working out a number of problems on the fly, using the console as a test bed for new concepts, shrugging off the mindset of the 8-bit Game Boy family and working toward the nearly unstoppable juggernaut that would be the DS.

A long-expected party

Game Boy Advance launched in March of 2001, followed a few months later by its U.S. debut. Its timing meant that its predecessor, the classic Game Boy, had an unprecedented 12-year run as the world's most popular handheld. Granted, Game Boy saw a few revisions in that time, including a partial upgrade in 1998's Game Boy Color, but GBA represented a true generational leap rather than what amounted to a cosmetic overhaul. In fact, GBA technically counts as two generational leaps, as its 32-bit processor skipped right over the 16-bit format from the 8-bit chips that powered Game Boy and Game Boy Color.

GBA wasn't supposed to be so long in coming, though. Nintendo began development on a proper Game Boy successor in 1996, or perhaps even earlier than that; the hardware's code-name, Project Atlantis, stood in reference to the company's initial plan to release it concurrently with that summer's Olympic games in Atlanta, Georgia. Project Atlantis featured many of the same specs as the eventual GBA hardware, such as a 32-bit RISC processor and a color screen.

While Nintendo has never (to my knowledge) explicitly stated this, Project Atlantis seems likely to have come into being as a response to the clear and looming failure of the Virtual Boy project. Initially touted as a Game Boy successor, Virtual Boy offered an incredibly clever technological hack that also made for an utterly impractical format for portable gaming: The machine came in the form of self-contained VR headset-like object that required a stable surface and a healthy supply of electrical power. Reception to Virtual Boy quickly degenerated from cool to hostile, and Nintendo sunsetted the device before its sales even reached a million units — a devastating failure for a gaming giant that, until that moment, had appeared unbeatable.

Project Atlantis took things more or less back to basics. The original hardware design resembled a somewhat bloated version of the classic "brick" Game Boy: Designed in an upright format with a screen in the upper portion and controls arranged below. It would have been a much larger device than the Game Boy — based on a slide Nintendo producer Masato Kuwahara showed at a Game Developers Conference panel in 2009, the device was a dead ringer in both design and size for NEC's TurboExpress.

Project Atlantis would have been roughly four times the size of the Game Boy's Pocket hardware revision, which also debuted in 1986. While it's somewhat unlike Nintendo to create less elegant technology than more, the mid-’90s saw the company at its most willing to play by the rules of the games industry arms race. And the notion of a dual release for Game Boy Pocket and Project Atlantis makes sense: The former would have been the compact, low-cost, end-of-life version of the obsolete system, similar to the revamped NES and Super NES models that launched at the end of those consoles' lives; the latter would have been the larger, pricier, more powerful device. The next generation. The machine for serious gamers who liked to play it loud, as one did in the ’90s.

For whatever reason, though, Project Atlantis didn't make its intended launch date. It slipped from a summer release without ever being announced, remaining the stuff of rumors and speculation. And then, surprisingly, before long, Project Atlantis didn't need to exist. A quirky little game called Pocket Monsters launched in Japan in Feburary of 1996 and steadily snowballed over the next few months into a massive, viral hit. The unexpected success of Pokémon and the arrival of the inexpensive and ergonomically superior Game Boy Pocket a few months later gave the aging console a second wind. Publishers, who had more or less abandoned Game Boy by 1995, reversed course and began ramping up production for the system again... with Pokémon clones leading the charge, of course.

With the Game Boy's second wind came a bit of breathing room for Nintendo. Its profitable portable market was in no danger of drying up, and the demand for Pokémon made the 8-bit system perfectly viable for a new generation of game enthusiasts. The U.S. launch of Pokémon came two years after its Japanese debut, and a few weeks later Nintendo introduced a stopgap update to the Game Boy, the Game Boy Color. While not the true leap older fans demanded from the system, the Color upgrade proved a massive success, ultimately seeing nearly as many games in its four years of existence as the black-and-white Game Boy did in about 10. It also helped Nintendo curtail the threat of Neo Geo Pocket and WonderSwan, new handheld competitors that more directly targeted the Game Boy's combination of low cost and low power than the beefy-yet-expensive SEGA Game Gear and Atari Lynx had.

Most of all, though, Game Boy Color bought Nintendo some time to get things sorted out with Project Atlantis, which eventually evolved into the system that debuted 15 years ago as Game Boy Advance.