Keiji Yamagishi on His Past and Future in Game Music

COVER STORY: The artist behind Ninja Gaiden's NES soundtrack opens up about returning to composing, and his future plans.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

USG: There were several publishers on Famicom who had very distinct sounds. Konami had a very distinctive drum sound, Capcom always had a lot of layering in its music. But I feel like the music you created also had a sort of distinct style. What would you describe as your signature?

KY: I definitely agree that music from Konami and Capcom did sound good. One thing I want to mention is that as I said before, I don't have a formal education in music. So I don't have much understanding of musical theory. So it could be maybe random in that sense — I played it by ear, so to say. Tecmo's sound composers were like that. Without the formal education, we thought maybe we weren't as good as the people at Konami or Capcom. If you look back at it now, perhaps we did do a good job.

But I guess if you needed to define the signature sound, there's one sound channel on the Famicom that you can use for sampling, so we ended up using it for drum sounds. I think as far as signature sound goes, that's probably what sets our work apart from other people.

USG: Did you create those samples yourself?

KY: Yeah, I had to make them myself, because Nintendo didn't actually share their tools with other companies. So we kind of had to figure out a way to make it on our own. So I did make that, and it being a specific, unique Tecmo technique we used, maybe the drums that we made sounded distinct from any sound that other companies made.

USG: One of my favorite things about Ninja Gaiden was the music, the audio test mode player. Was that something you wanted to add to the game, or did someone else put that in?

KY: That's all the main programmer's work. That was supposed to be a hidden feature, or a hidden test function, but the programmer just kind of put it in the game himself, and it ended up shipping to consumers. So apparently there were some — not rumors, I guess, but people talking about that back in the day as well.

USG: Yeah, the code for it appeared in a magazine, Nintendo’s magazine in America, so everyone who played the game knew about it. Just as a silly personal story, when I was in school, my friends and I would create radio programs on audio tape for school projects – like dramatic readings and that sort of thing. And because Ninja Gaiden had a sound test, we would sit there and use the music from the sound test as the background for our radio dramas. So we’d be reading the drama and then we’d be fiddling with the controller to get to the right musical piece so that we could queue it up and play sound effects and music at just the right time. So I guess I need to thank you for that.

KY: [laughs] In elementary school?

USG: Middle school.

KY: [laughs] Thank you as well!

USG: Anyway... you mentioned you were basically Tecmo’s one Famicom sound composer; was that always the case, all the way through the end of the Famicom era? Or did they eventually bring on more people?

KY: Oh, they brought on more people. Yeah, the following year, more people joined on, so it wasn’t just me.

USG: As the workloads diversified, were there any particular games or franchises that you felt particularly fond of and really looked forward to working on?

KY: I guess to answer your question, I mean, Tecmo didn’t release that many games back in the day, so I actually had no choice as to what he would actually work on. So in that sense, you know, it’s not like I could particularly look forward to working on a specific project, right? Whatever they decided to make is whatever they decided to make.

That said, if there was one game I wish I could have worked on, it was Klonoa. It was my friend, [Hideo] Yoshizawa-san, who was the director of Ninja Gaiden... he went on to Namco to work on Klonoa.

USG: Of all the games you worked on at Tecmo, is there any one project that you worked on that you think, “This was my greatest Famicom composition”? What would you like for your fans to listen to and really, really enjoy?

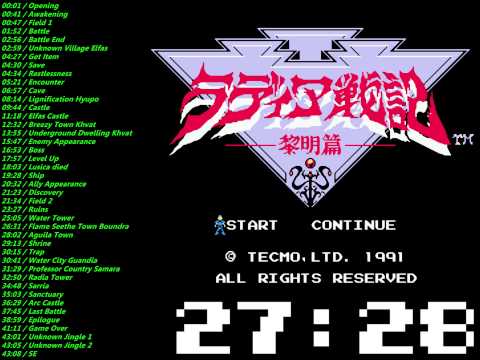

KY: I've mentioned this before, but Radia Senki, the last game I worked on for the NES, would be the one that I'm really particularly proud of. Being the last game I worked on, it was kind of, you know... I used every technique and every method that I'd learned, right? So it’s kind of a culmination, like it symbolizes how far I had come as a composer. It shows my development and, you know, how I “mastered” the Famicom.

USG: After Radia Senki, what was the next phase of your career?

KY: So after that, I went to Koei, where I did some SNES and PlayStation games, and then after that, I ended up becoming a manager, doing management-related work. Since then I haven’t done much on the gaming music side.

USG: So the Super Famicom used – and PlayStation, too – composing for them were I’m sure very different from composing for the Famicom. Can you talk about the differences there, and the challenges and processes you encountered as you went from one piece of hardware to the next?

KY: Well, the Super NES used sampling. So – and it was still a cartridge-based system, so a lot of limitations were still present, but the Super NES required a lot of experimentation to see whether the sound you’d generate would go well with the game. So I guess a lot more experimentation than there was before.

USG: And then PlayStation, how was that different?

KY: Honestly, the PlayStation, I didn’t do much work on it. Shortly after it came out, I had become a manager, so the little that I did do on it... I had two choices. Since it was a CD-based system, I could use pre-recorded music and dump it into the CD player and then just play it out through there. Or I could also use the sound chip of the PlayStation.

If you did use the sound chip, it would be similar to what I did with the Super NES, just experimenting with what sounded good. Or you can just use pop music or whatever. Things that you record in the studio. I never actually ended up recording music in the studio himself, because I didn’t stay long enough to really end up doing anything like that. Yeah, so my experience is actually quite limited, but those would be some of the big differences that you can point out, for working with the PlayStation versus earlier systems.