JPgamer: The Art of Penmanship

Is the perception that video games -- particularly those of Japanese origin -- have "bad writing" a particularly helpful or fair criticism? Pete ponders the matter, and manages to get a mention of Squid Girl in there in the process.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Video games have a bit of a perception problem. Actually, they have lots of perception problems, but one of the most grating ones for me personally is the frequent assertion that games in general have "bad writing." Japanese games are hit particularly frequently with this accusation.

It's not always an unfair accusation, of course. Few would argue that the borderline nonsensical campaigns of the last few Call of Duty and Battlefield games will ever take their place alongside classics of literature -- or even the here today, forgotten tomorrow world of bestselling books -- but that doesn't necessarily mean that, across the board, games have bad writing.

"Bad writing" is in itself a meaningless criticism, anyway. Say to someone that something is "bad" or "horrible" and it means nothing; it tells them nothing. Rather, it pays to explore why you think something might be "bad" -- or perhaps the opposite, thinking something is good when it attracts widespread denigration. Is it because you couldn't relate to it? Is it because it was written in a style that you didn't enjoy? Did it include subject matter that offended you? Or did you just think it didn't make a whole lot of sense?

Out of those possible reasons -- which aren't the only reasons to think something is "badly" written, of course -- most of them are opinions; personal responses to a work. And if you don't like something? Well, that's quite different from it being unequivocally bad. One man's meat is another man's poison and all that, if you'll pardon the cliché.

There are far too many examples of games that have been dismissed by critics as being "badly" written to nitpick right now, but it's worth exploring a couple of possible reasons for people to respond to them in that way. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list; more a pondering as to whether or not the criticisms are justified.

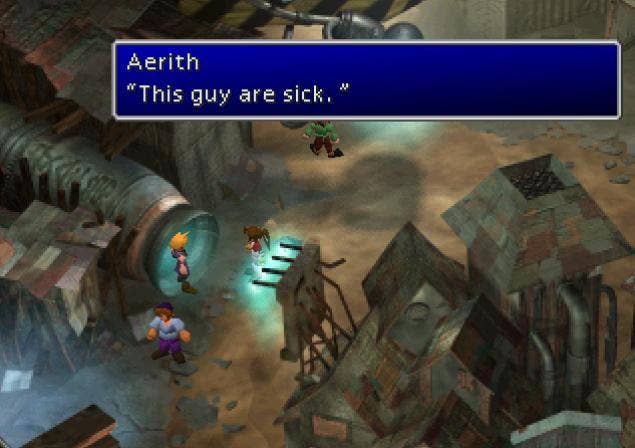

One big reason why Japanese games in particular often get slammed for "bad writing" is not actually because of the story itself in many cases; it's more to do with the translation. And we've come a long way over the past few generations: from Final Fantasy VII's "this guy are sick" to the stellar work localization specialists like Xseed and Aksys do on modern Japanese titles.

Translating from Japanese is a difficult process since it's such a different language from English. And I'm not just talking about the different ways of writing; the way the language is structured and used is completely different, too. In Japanese, puns and idiomatic expressions are often expressed through playing around with the last word in a sentence, which is usually the verb. Moe characters such as Compa from Compile Heart's Hyperdimension Neptunia series regularly add "desu" to the end of sentences, for example, even where it's not required -- for those unfamiliar with Japanese grammar, "desu" is a "copula," or a word that links the subject of the sentence with the verb, usually intended to mark a sentence that is a statement. Excessive use of "desu" is a hallmark of particularly adorable characters in Japanese media generally -- not just games -- and yet there is no direct equivalent in English, so how do you translate this?

Alternatively, take a character like Zero III from Virtue's Last Reward, who presents himself as a rabbit. In Japanese, he replaces the "desu" at the end of his statements with "usa," from "usagi," Japanese for "rabbit." Again, there's no direct English equivalent for this, so Aksys chose to translate his peculiar manner of speaking into a string of excruciating rabbit-themed puns ("Lettuce begin! You carrot escape!") for roughly the same effect. Like excessive "desu"-ing, it's not just games where this happens, either; the anime Squid Girl also takes this approach with the titular character's use of "de geso" ("squid tentacles") as a copula and replaces it with similarly cringeworthy squid-based puns in the English translation. Squidn't that tentacular?

Anyway, the point is that localization is not a simple matter of loading kanji and kana into Google Translate and then copy-pasting the resulting broken English into the game's script. Early games may have got away with an approach like this, but a modern English-speaking audience expects better these days. This raises its own set of considerations, though: how strictly do you stay to the original script?

In stories obviously set in Japan, this would seem like an obvious answer: titles like Atlus' Persona series keep the dialogue with all the -san, -kun, -chan and -senpai honorifics intact because it makes sense for them to do so. These games are set within a real-life society with a real-life social pecking order that is explicitly reflected in the way that people refer to one another. There is not really an English equivalent to "senpai" for example -- and no, saying "upperclassman" doesn't count -- so it makes more sense to simply keep it as is rather than butchering the script and the characters' relationships in the process.

That's not always the case, though. The Ace Attorney (or, more accurately, Gyakuten Saiban) series is very obviously set in Japan -- look at how Maya dresses, or the heavy degree of spirituality in the stories, or the frequent sightings of Japanese architecture and cultural phenomena -- and yet the team at Tezuka Productions chose to ruthlessly Westernize the game's dialogue to such a degree that it's almost unrecognizable from the original script: an approach they also took with the indie game Cherry Tree High Comedy Club. The new scripts were wonderful, occasional typos aside -- just not very true to the originals.

Both approaches have their pros and cons. Tezuka's ruthless approach to localization is more friendly to those who aren't already immersed in Japanese or otaku culture -- and consequently more appealing to a mainstream audience -- but less faithful to the original script. By the same token, translations that keep a more authentically Japanese feel to them can be more difficult to understand for newcomers, though they can also, when handled well, provide a good means of educating players about another culture through immersing themselves in it. The visual novel Steins;Gate is a particularly good example of this sporting, as it does, a comprehensive glossary that explains any piece of otaku or Internet slang as it comes up along with Japanese cultural concepts that might not be familiar to a Western audience.

Even a clunky translation doesn't have to spoil a good story, though. The visual novels Kana Little Sister and Kira Kira both have localizations that are not only rather stilted in tone, but also riddled with textual errors. And yet both of them manage to transcend the limitations of their questionable, overly literal translations to tell compelling, emotionally engaging stories that will have all but the most iron-willed readers in tears by the end of the experience. And they're far from the only examples of this; think back to the first time you played the aforementioned Final Fantasy VII -- did the indecipherable gibberish the characters spouted affect your enjoyment of the story? I'd wager not; in actual fact, I found the technically superior translation of Eidos' PC version to have considerably less charm than the garbled original when I played it a year or two later.

So a bad translation doesn't necessarily equal bad writing, even in extreme cases. What about another important consideration, then: the way you, personally, respond to something? Does a work failing to resonate with you -- or, in some cases, even repulsing you -- make it badly written? Again, I'd argue not, and in the latter case I'd argue that something actively repulsing you is evidence that it's actually doing a good job, even if you might not necessarily be enjoying yourself.

I was talking to a friend about Nippon Ichi's The Witch and the Hundred Knight earlier today. He commented that he'd heard some things that had put him off from playing it -- specifically, a scene early in the game where the titular witch Metallia defeats her rival, exacts wince-inducingly violent revenge on her, then finally turns her into a mouse, summoning a handful of horny male mice to chase her off-screen, with the implications being obvious. He referred to the online poster who had described that scene and how they felt this had made Metallia into a "wholly irredeemable" character -- so much so that they couldn't even summon up the willpower to keep playing.

That poster's response was entirely valid. At the outset of The Witch and the Hundred Knight, Metallia is a loathsome character, utterly shameless in her egocentric evildoing, and it's perfectly understandable for people to dislike her for it, even to such a degree as to do the video game equivalent of walking out of the theater. But that doesn't make her a badly written character. Again, I'd argue that to feel such a strong emotional response to her and her actions is a sign of good characterization -- moreover, this sort of tragically flawed protagonist is something I'd very much like to see more of in games. And I'm not talking about the gritty anti-heroes who ultimately come out on top that we see in a lot of modern triple-A games; I'm talking about the Shakespearean ideal of a tragically flawed character -- one who begins their story already fucked up in some way, and one whom you suspect won't necessarily enjoy a happy ending by the time the credits roll.

There are also cultural differences to take into account, and the related fact that depicting something is not the same as endorsing it. Japanese media is, in general, a whole lot more willing to explore subject matter we find distasteful in the West, and this can lead to accusations of games being anything from gratuitous to pandering. While it can be helpful and interesting to comment on these things from a Western perspective, perhaps criticizing them and pondering why there's such a rift between East and West on some topics in the process, it is also important to bear in mind the original cultural context in which they were presented. In some cases, we're lucky to see certain games at all, and all credit to dedicated niche publishers like NIS America, Idea Factory International, Xseed and Aksys for taking a chance on games like Senran Kagura and Monster Monpiece for which it's practically a given that they'll be heavily criticized by the dominant ideologies of the day.

Art should challenge us to consider alternative viewpoints and engage with characters that aren't necessarily in keeping with our own personal values. Art doesn't have to be a persuasive piece attempting to change our mind about something; it can simply help us understand things in a different way, and perhaps even reinforce the beliefs we held in the first place. Art doesn't have to be enjoyable or even comfortable to experience, but if it isn't, that doesn't make it bad. It may end up being something you don't want to engage with personally, and that's absolutely fine; but there's likely someone, somewhere out there who finds value in it. Let's try to avoid devaluing and belittling what people enjoy by making sweeping and ultimately unhelpful statements like "this has bad writing."

Unless, you know, something really is completely, utterly and irredeemably awful. But in my experience, that's pretty rare.