Inside the Greatest Game Gadget That Never Was

Alex Bahr's homemade SD Card Drive perfected the iconic Game Boy Camera — but it never evolved beyond the prototype stage.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Originally published June 2015.

Video game peripherals are never, in my experience, cool.

This year's E3 served as a stark reminder of that fact. Virtual reality headsets commanded much of the show's buzz, and the concept has definitely come a long, long way since the early days of boxy '90s polygons gliding across checkerboard floors. The elephant in the room, however, is that everyone looks like an absolute tool while wearing a VR headset.

Microsoft's "no photos" rule for Hololens demos suggests that the technology's peddlers know it, too. Jaz couldn't say enough good things about the Halo 5 Hololens demo, and I can confirm from first-hand experience that the Minecraft "experience" is as fantastic as the press conference demo would suggest. But the fact that Microsoft's handlers wouldn't let us commemorate our experiences by taking a Hololens selfie means they're well aware that we undoubtedly looked ridiculous — a couple of pasty white dudes pretending to be cyberpunks — and don't want the intrinsic dorkiness of Hololens' reality outside of a carefully staged press conference to undermine public perception of their very young and very expensive tech.

No, the best any game peripheral can hope for is to achieve a sort of tongue-in-cheek popularity despite itself. Mattel's Power Glove for NES, for example — no one (or at least no one with any degree of social awareness) thinks the Power Glove is legitimately stylish. But because it played a memorable role in the glorified Nintendo commercial that was The Wizard, the Power Glove has a sort of smirking, tongue-in-cheek appeal. It's at once ironic and iconic; you look like a doofus for wearing it, but that's kind of the point.

There remains, however, a single notable exception to this rule — a device that manages to have both sarcastic hipster cachet and genuine everyman appeal: The Game Boy Camera. Launched late in 1998, the GB Camera was a relic even at the time of its debut. It arrived right around the time the Game Boy finally burst beyond the boundaries of four-shade monochrome visuals through the Game Boy Color, yet the Camera was shackled by the limitations of the original greyscale hardware. Its photo resolution didn't even make use of the full 160x144 resolution of the Game Boy's tiny screen; photos ended up displaying a thick border, despite their tiny pixel dimensions. Even in 1998, digital cameras started at 16-bit 640x480 resolution and went up to 24-bit two-megapixel resolution, making Game Boy Camera laughably anemic by comparison.

And yet, it's precisely these seemingly suffocating limitations that make GB Camera so charming. There's the novelty of taking photos with an archaic piece of game hardware; everybody remembers the Game Boy (I still hear people call Nintendo 3DS the "Game Boy 3DS"), and all but the most curmudgeonly of hearts have a soft spot for it.

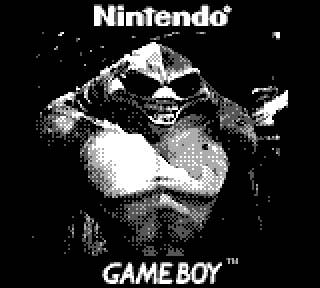

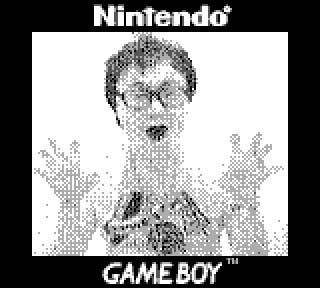

But really, GB Camera's appeal rests in the fact that, like the system that powered it, its functionality sits at the threadbare edge of "bare tolerability." Because the GB Camera shoots at such low resolution and in four shades of grey, its images take on an almost abstract quality that completely sidesteps the arms race to better photo fidelity. Nearly 20 years later, we all carry tiny networked supercomputers in our pockets, each equipped with camera lenses that vastly outperform and overpower anything that was on the market in 1998. And yet, this tech has become so commonplace that it's grown mundane; your phone can capture print-quality images and instantly apply any number of filters to them, and it's no big deal. GB Camera, on the other hand, is so anemic, so barely functional, the fact that it can snag even a slightly recognizable image of your own face feels like an incredible accomplishment, or at least a fun party trick. Like teaching a parrot to recite pi to the 100th digit.

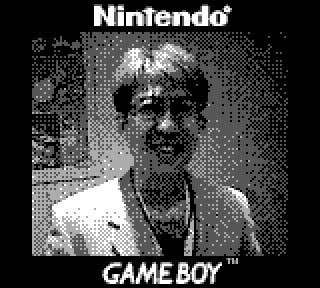

The GB Camera had a sense of cool back when it was new — go back and check out all the games magazines that suddenly suffered an outbreak of tiny black-and-white snapshots early in 1999. How crazy was it that you could use a game console to take all these photos? These days, Game Boy Camera seems interesting for entirely different reasons: How crazy is it that such a thing existed and still works? In fact, I took a GB Camera along with me to E3 last week in order to capture some low-rez images of game developers and interesting sights on the show floor, and it always elicited a sort of fascinated curiosity from subjects and bystanders alike. Nintendo's Kensuke Tanabe in particular had a sort of faraway look in his eyes as he exclaimed, "Wow, I haven't seen one of those in ages!"

Myself, I fell in love with the GB Camera about a decade ago, having been something of a latecomer to the device; by the time I started carrying one around with me, it was already obsolete and forgotten. But I quickly discovered there's an art to the thing; you can't simply point and shoot with GB Camera. The sensor needs a couple of seconds to adjust to new lighting levels and resolve into an image, and even then you'll probably need to tweak the brightness and contrast settings on a per-photo basis. In a lot of ways, the GB Camera feels like an analog camera experience in a digital form, and there's a certain sense of satisfaction that comes from using it to create a well-framed, well-balanced image that maintains visual clarity despite its minute resolution and (literally) two-bit color depth.

The fundamental problem with Game Boy Camera, I quickly learned, was that despite it shooting in a digital format, images become essentially trapped on the device. Aside from a print feature that outputs Camera images to the Game Boy Printer (a cheap, battery-powered thermal printer that shipped alongside the GB Camera, but separately), there's no way to extract all those tiny, abstract masterpieces from the gadget.

I certainly gave it my best effort, though. I tried scanning GB Printer printouts, which didn't really work due to the faint, fuzzy quality of the printer's thermal output. I hooked up a Game Boy Player to a video capture card and snapped frames, which then had to be cropped and processed. I even rigged up a Photoshop action that would allow you to simulate (with impressive accuracy, I should add!) the GB Camera look. Still, none of it felt 100% authentic.

In fact, there's only ever been one solution for transferring GB Camera images directly to computers: A MadCatz link cable peripheral that allowed players to "print" to a PC parallel port in BMP format. Not a bad idea, but even more obsolete these days than the GB Camera itself. Who still uses a computer with a parallel port?

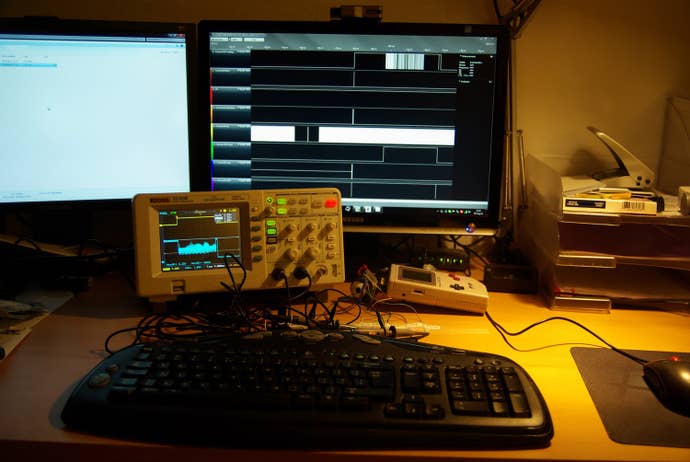

Enter Alexander Bahr, a German engineer and video game fan who almost solved the GB Camera's nagging shortcoming with a self-contained device capable of saving photos to a SD card, which could then be transferred to any computer: The Game Boy SD Card Drive. I say "almost" because Bahr never took the gadget past the prototype stage; though he put together a Kickstarter page for the project, he never pulled the trigger. For $49, backers would have received their own SD Card Drive, but real life got in the way.

Bahr explains, "Starting a company plus having a baby equals no time for a Kickstarter, which would at best break even."

Bahr's prototype device works much along the same lines as MadCatz's old parallel cable system: It plugs into the Game Boy's serial port and emulates a Game Boy Printer. But instead of transferring images to thermal paper, the SD Card Drive converts the print signal to a BMP file, which it then saves to an SD card. The result is a crisp, perfect, true-resolution Game Boy Camera image (complete with border) in a format that works on practically any digital device that reads SD cards — which, these days, is most of them.

Bahr came about his inspiration for the gadget indirectly. It began not as a way to rectify a failing in the Game Boy retro accessory marketplace, but rather as a thought exercise for a thriller novel.

"The whole project started back in 2011," he writes, "when a friend of mine asked me to come up with a scenario for a book he was writing, in which the two protagonists break out of makeshift prison cell with the help of a Game Boy equipped with a camera. The book was the final chapter of the 'Extraleben' trilogy. The books are about two guys in their late 30s stuck in dead-end journalist jobs (not game related), with a love for retro games and also fixated on the '80s in many other ways. They get sucked into a thriller/road-movie story where the help of old games turns out to be quite helpful, thus redeeming themselves leading to the titular "Extra-life". It actually comes together quite nicely and makes for a coherent and at least somewhat plausible story. The books were quite a success in Germany, albeit a nichey one."

"So in the prison cell scenario, the locked protagonists rip out the head of the camera and attach the right lines of the camera cartridge body to the serial cable running to the cell's code lock. The idea being that the cable runs inside the cell, but hey, it's a makeshift cell. When you set it up right, the camera's processor sitting on the cartridge can indeed register 0s and 1s coming through a serial cable for 1/30 of a second. The Game Boy camera does actually turn into a single channel logic analyzer with a 1/30s capture buffer. The bits are then visualized as black and white bars on the Gameboy screen from which you can deduce the bytes, get the code, punch it in the code lock on your side, and our heroes free themselves for the great finale of the trilogy."

Soon, the fictional hack evolved into a real one. Bahr's meticulous tinkering, intended to lend his friend's novel a touch of authenticity, caused him to realize that he could potentially come up with a tool that others could make use of. An avid classic game fan himself (and an enthusiast for game-history-focused publications like Retronauts), Bahr set about exploring the possibilities of capturing the Game Boy printer signal for other uses.

"It was great project," he says. "I, being in a decidedly non-writing profession, found it particularly satisfying. As I was digging into the Game Boy Camera to come up with the hack for the book, I learned that there really is no way to get pictures off the camera without using a setup consisting of Windows 98 machines, parallel cables, obscure drivers, command line interfaces, and a set of hard-to-get contraptions. At the time, I'd already considered building an SD card drive for a late '70s HP-41 calculator, and I thought that doing it for the Game Boy Camera might be more useful. I fairly quickly had a first version, and when the author showed Game Boy pictures to the people illustrating his book, they loved the style. Game Boy Camera pictures ended up being the pictures for the chapter dividers."

Bahr's project was unfortunately curtailed by harsh realities — not only time conflicts, but also the limitations of Kickstarter. By the time the service finally established itself in Germany, he says, the ship had sailed.

"I would have followed through with it back in 2012/13, having a cushy 9-to-5 job and no kids. Time went on, though, and Kickstarter tip-toed around Germany by first going to every English speaking country (New Zealand, anybody?), and I gave up on the idea."

And so, the Game Boy SD Card Drive remains nothing more than some early hardware experiments and good intentions. Bahr produced a handful of working prototypes, which he's sent to a few people in the media — those with a pronounced affection for the Game Boy or for interesting peripherals. One of his prototypes ended up in my hands several weeks ago, which is why I took a Game Boy Camera to E3 — a sort of trial by fire for this would-be peripheral.

Tragically, the SD Card Drive works flawlessly. "Tragically", you ask? Yes, tragically — because it's a fantastic addition to the Game Boy that deserves to exist as something more than a small batch of hand-made circuit boards. Bahr's creation really is as simple as plug-and-play: You power it up with three AAA batteries, connect it via Link Cable to the Game Boy serial port — the drive itself uses a salvaged Game Boy serial port, so a standard Link Cable is all you need — and "print" from the GB Camera. A few seconds of flashing LEDs later, you've saved a digital Game Boy photo to your SD card. No additional software or tools required, besides a computer capable of accepting SD cards.

Despite the device's digital elegance, it nevertheless retains the analog clumsiness that makes Game Boy Camera so endearing. There's no way to simply strip the GB Camera's memory and do a photo dump at all once. You need to print each image individually, a process involving several steps and a couple of progress bars for each image. It's inconvenient compared to, say, dumping your iPhone's entire camera "roll" to Dropbox, but the ordeal of cycling through GB Camera images one by one and taking the time to print them adds a personal touch lacking in batch downloads. Like the process of taking GB Camera photos, saving them to disk requires a modest time investment. It's not efficient but rather intimate, and makes GB Camera all the more unique as a photographic medium.

And perhaps there's still hope that this device will eventually make its way into the collections of more than a small handful of podcasters. Since Bahr and I first corresponded at the beginning of the year, he's begun exploring the possibility of mass production avenues beyond doing it himself through Kickstarter.

"The good news is that in the past month, I further iterated back and forth with the Gameboyphoto people, who have been using it and are pushing me to get it made in small quantities, which they would sell," Bahr told me earlier this week.

A potential mass-production model would likely look more refined and portable than the raw, fragile device Bahr shared with me. "By their request, I ditched the 3 AAA batteries and put a rechargeable LiOn battery in with a micro USB port for charging, and I designed a case for it which is being 3D-printed right now," Bahr says. "In about two weeks, I should have that one slapped together.

"I personally liked the simplicity of the design where the AAA battery case provides protection for the electronics," he adds somewhat ruefully, "but the version with the case should look very nice.

"Anyhow, the message is that while the initial attempt to bring it to the fans has failed, there is hope now."

While the Game Boy SD Card Drive would likely never find anything more than a niche audience — not when iPhone apps exist that can produce a passable if imperfect imitation of Game Boy Camera output — I share Bahr's hope that his invention eventually makes its way into wide production. The Game Boy Camera remains a magnificent hack of a gadget, and it's also one of the most unique and artful forms of photography ever invented. The SD Card Drive greatly expands its modern-day utility, with its hoops and complications making it resemble a sort of 8-bit darkroom process. As a game accessory, it'll never drive the kind of hype that VR headsets do... but on the other hand, it would be far more stylish.