Inside the development crunch pandemic - part two

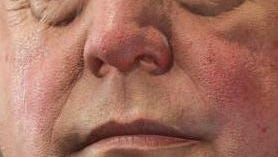

Talent burnout, hospitalisation and a culture of fear - is this what you sign up for when you enter games development? VG247's Dave Cook continues his investigation into crunch.

You can find the first part of this feature here. In it, we discussed how Crytek's tweet about Ryse: Son of Rome's crunch period saw it hit by a public backlash, and I hear from developers working within the industry today about why they feel crunch happens. There are some pretty harrowing stories in there, some of which we elaborate on below.

Working cultures vary on a company-to-company basis, so it's clear that the definition of development crunch time is both malleable and occasionally misrepresented. Several developers told me that yes, crunch is a disruptive aspect of development typically born from issues above their pay-grade, but in some cases it is entered into willingly to ensure projects ship at a certain level of quality. Games take years to create after all, and no one really wants to ship a poor product after all that work. Pride, it seems, is a double-edged sword in the games industry.

"I know people who have been hospitalised because of overworking. Alcoholism and substance abuse isn’t unheard of. Crunch isn’t a healthy lifestyle but, to a teenager, spending all night making video games and eating pizza sounds like a dream.”

In one instance, a UK-based developer told me that crunch founded in enthusiasm and that sense of pride should be distinguished from examples where overtime is forced. They explained, "I'd like to distinguish independent developers doing overtime out of a genuine love and enthusiasm, and larger developers mandating overtime in order to ship a product on time. I would never want to stop the former, but it can often muddy the waters when discussing the topic.

"There is also a element of bravado and trading war stories such as, 'the time I rushed back from a gig in London to fix a build, and got out of the office at 5am,' and, 'spending weeks doing a full UK working day, then staying in the office for the Californian working day in case the publisher had any problems.' While this feeling of camaraderie can at times be fun, it should not be seen as a genuine positive of crunch; this is resilience in the face of a bad situation.

"Mandated overtime means burning out talent, driving people out of the industry, and short-sighted thinking. Particularly for programming, it is ultimately self-defeating - once you reach a certain level of sleep deprivation, then you are creating more bugs than you are fixing. I know that for myself and many programmers, the best ideas come not while staring at a screen, but in the shower, or even the very moment I step out of the office and into the fresh air. Time spent in the chair is only loosely correlated with amount and quality of work done."

I was repeatedly told that the definition of crunch can vary from a few hours overtime and a free pizza on your desk, to a full week of 12-hour shifts without compensation. The only constant is that either small or significant, any amount of overtime results in the disruption of a person's work-life balance. Getting home late is one thing, but turning your social and home life on its head can bear serious mental and physical ramifications.

Unfortunately, this happens more than you'd want to believe and can result in fractured relationships, divorce and in one interviewee's experience, thoughts of suicide. Some of the developers I spoke with revealed that their bosses regularly played the guilt card when trying to off-load their role in crunch, and countered that they should feel privileged to work in such a booming, fun industry. It's easy to overlook the 'cool,' 'laid-back' image of the hip game designer chasing their dream when you're working yourself into an early grave.

How damaging is crunch time?

Legislation governing what constitutes fair working hours varies from country to country. Here in Europe, the Working Time Directive states that EU workers have a legal right to a set holiday allowance, an 11 hour break for every 24-hours worked, and a cap of 48 working hours in any given week. Based on stories from my interviewees, such rules are regularly, legally broken within the games industry, and it was suggested that both internal HR departments and management are either unwilling to comply or change the working culture to fair standards.

"Taking a mental health day, just to get away from work for no real ‘reason,’ is maligned, ridiculed, or outright denied in a lot of cases. A lot of employers frown on taking vacation, even when that vacation is paid and a part of the employee’s compensation.”

If crunch is considered bad here, then reports coming out of China's Foxconn manufacturing plant suggest that the nation's working culture is worse. One employee at a Chinese firm told me, "Two of my colleagues got so depressed from the work and hours that we were doing that some of us were afraid they'd do something stupid. Maybe not suicide, although it did cross one of the two's mind - he told me as much a short while ago - but certainly just running away without any preparation."

It's hard to fathom something as radical as simply up and leaving your place and work with no plan B, but it's telling that these employees considered it. Other interviewees stressed that crunch understandably increased when they decided to start a family, while another stated that their colleagues became irritable once work mounted. Eventually, the sound of friends screaming abuse at one another across the office became a regular occurrence. The common image of workers lying awake at night, unable to sleep due to stress was also cited, and one respondent revealed that a friend's wife asked him for a divorce due to the time he was spending at work.

Another employee - who currently rates his social life as "non-existent" - stated, "I've seen and experienced both physical and mental damage during crunch periods. I and others gain weight during crunch because the food provided is usually unhealthy (snacks and take-out meals for dinner). It's also much more difficult to exercise regularly. I've personally had emotional breakdowns and experienced lots of stress because I've felt like I haven't been effective enough at my job. I've seen colleagues leave the industry because they couldn't do it any more."

The point at which work impedes dangerously on a person's well-being is subjective, as we each have our own tolerance for stress and capacity when working above and beyond our job descriptors. It's reasonable to assume that a company - any company - would begin to take stock of its working practices, should an employee take ill as a result of being over-worked. For one of the developers who stood forward to speak with me, that simply didn't happen.

"I know people who have been hospitalised because of overworking," they said. "Alcoholism and substance abuse isn't unheard of. Crunch isn't a healthy lifestyle but, to a teenager, spending all night making video games and eating pizza sounds like a dream. I've worked with young people that see this as a right of passage and aspire to be working in a team doing exactly that. Have you ever tried telling a teenager not do something that'll harm them longer term? Yeah, good luck with that."

They added, "Every studio wants the best for their employees, without question. I know of various studios that have tried to pay overtime or have rules like 'no crunch' and all of them have failed and no longer exist. I'm not saying that crunch means success, far from it. The issue is that getting the freedom and means to do the best for your employees means you need stability and money. The games industry isn't stable. The games industry is a constant gamble and the illusion of stability that a publisher brings with his big chequebook means unreasonable deadlines and crunch are sure to follow."

"I saw a colleague actually sleep under his desk prior to E3 a few years ago. He’d just had a kid and was spending his evenings glued to server builds and not seeing those moments. That was when I made decision to get out AAA.”

We're back in familiar territory now. It should now be clear that crunch is a regular problem in the games industry, and one that goes hand-in-hand with money. If clients - typically a publisher or hiring studio - are to keep funding a team, they will expect projects to be completed on time, within budget and with little complication. That means no changes to their master plan, no costly amendments and for the title to be shippable by launch. The targets simply must be met, even - it seems - if it costs employees their health and home-life.

One producer told me that his background is littered with crunch woes, and that he now works at a small indie studio. Part of his job is to actively avoid over-working his staff throughout development. He stressed, "Work-life balance is important for staying sane, staying healthy, staying motivated, and staying engaged, and even the most ardent, dedicated employee will get burned out eventually if all they do is work.

"It shows in their attitude and in the quality of their work, and if it goes unaddressed, it can have a ripple effect on the people around them. I think it's important to have someone at work, whether it's HR, a producer, a lead, or the CEO, who's job (or part of it) is to ensure that the studio, and all the employees in it, maintains that balance as much as possible, even outside of crunch. If an employee is an asset to the studio, as every employee should be, someone at work should be empowered to say, 'You're hitting it too hard. Go home and get some rest.'"

"I think there's a stigma against self-care," he added, "not only in the games industry but in a lot of jobs in the United States. Taking a mental health day, just to get away from work for no real 'reason,' is maligned, ridiculed, or outright denied in a lot of cases. A lot of employers frown on taking vacation, even when that vacation is paid and a part of the employee's compensation. It's a culture that encourages or even demands that people put work before all else, and crunch is the worst-case example of that."

It would be interesting to see just how many game studios out there actively employ someone to monitor workplace stress and to take steps when a worker is clearly suffering as a result. Human resources teams are a staple in many companies, but when I asked my interviewees if their own departments saw any real HR assistance during crunch, or other forms of compensation, the idea was routinely scoffed at.

Can anything be done?

You'd like to think that there's always someone to talk to when work starts to negatively impact your life. On more than one occasion, the developers I spoke with revealed that they had been laughed at when highlighting problems to their resident HR professionals, with one person saying that HR simply, "aren't on your side.' This paints a worrying image of how crunch time is regarded in the games industry. I asked the group if their superiors really felt that the problem is immune to change, and if they were ever offered any rewards for their extra effort.

In one instance, an interviewee told me that their workplace only recently established an HR department, while another explained that in their experience, being paid extra for an unreasonable amount of overtime simply didn't happen. "I've never heard of anyone being paid overtime during crunch. The overwhelming majority of people I know in the industry are salaried, and it's very easy to overlook things like overtime when you're a salaried employee.

"I think the games industry is one of many industries guilty of exploiting the salaried/hourly (or exempt vs. non-exempt, in reference to overtime guidelines) delineation of employees, greatly to the benefit of the employer. If studios had to pay out overtime for all their employees, I think the work-life balance and the attitude towards crunch would be a lot different."

"You were deducted year bonus ‘points’ for leaving at six, even if you only did it once a week. Six or seven day weeks were also not at all uncommon. When we saw the tweet from Crytek my colleagues and I joked to each other that at least they got their meals fully compensated.”

Recalling a notably flagrant breach of HR policy, one UK developer claimed, "I saw a colleague actually sleep under his desk prior to E3 a few years ago. He'd just had a kid and was spending his evenings glued to server builds and not seeing those moments. That was when I made decision to get out of AAA." He added that the possibility of overtime is often written into work contracts, and that most experienced employees instantly recognise it as an inevitability, rather than something that may occur. He agreed that if you're lucky, you may even be provided with guidelines on how to deal with the extra workload and minimise any attached health issues.

Speaking of HR guidelines and contracts, another British employee stated that while all the studios he knows work to comply with employment legislation, they also work opt-outs from the Working Time Directive into employee contracts knowingly, meaning they can be overworked without repercussion. On potential compensation he added, "Here is where it gets really dodgy: bonuses. Or at least the hope or promise of a bonus. The temptation for crunch is that the game does better, sells millions upon millions and everyone gets to be the next Scrooge McDuck, swimming in gold. Never happens. Unless you're the publisher."

In Japan, one developer stated that his previous firm doled out bonuses as reward for hitting an "imaginary milestone," and and suggested that it was "hush money," more than anything else - a way to keep employees both compliant and to stop them from talking about their treatment externally. When I asked if he had ever approached the company's HR department to raise a complaint he simply replied, "Hehe. Good one." My interviewee in China then added that when he raised crunch to his superiors he was simply told, "We don't do crunch", and nothing more was said on the matter.

I quizzed another developer in China on the issue of HR and attempts to hear out employee concerns. They told me, "There was an overtime clause in the contract which I signed before I moved there, but when I arrived they told me it was a lie and the head of HR laughed at me. These were western people working in China. Work weeks of 70+ [hours] were absolutely the norm for quite a long time.

"You were deducted year bonus 'points' for leaving at six, even if you only did it once a week. Six or seven day weeks were also not at all uncommon. When we saw the tweet from Crytek my colleagues and I joked to each other that at least they got their meals fully compensated. Quite a few people around me actually just browsed the internet half the time, because they knew they were required to stay late anyway or else they'd incur the wrath of HR."

It seems almost foreign to hear about working environments where the benefits of human resources simply do not apply, but it sounds both morally and professionally unjust to force a 70 hour working week on an individual without the right to reply. In some cases these people have been threatened with deducted bonuses and plainly ridiculed for daring to speak up. It's understandable then, that they all asked me to keep them anonymous in this piece. When employees are afraid of speaking openly to their superiors about workplace issues without feeling like they will be punished, that's the hallmark of a fear culture, pure and simple.

But surprisingly, while most of the developers had negative experiences to share, a few of them had since moved on to companies that have always tried - or were at least recently trying - to combat the negative aspects of crunch. If there's a silver lining to take away from some of the horror stories in this and other articles on the matter, it's that some - not all - studios are now appraising the working culture and looking for ways to take the strain away from employees. However, it will take time to gauge if these efforts are bearing fruit.

Silver linings?

One developer in particular seemed to get lucky with several employers. "At my first firm we were promised bonuses, whatever the amount of time we spent working," they explained. "Sometimes we got it, sometimes we didn't. In my current firm we don't get paid overtime, but we can get a few days off after the crunch, or some comfort like longer lunch breaks, leaving home early in the evening and that sort of thing.

"Once, after a short crunch time, the firm rented a whole video game arcade for an evening with the machines unlocked and we were allowed to order any food we wanted, all on the house. There were prizes to win such as PS3's and 360's, Kinects, Razer computer accessories. So no money, but a big big thank you."

"The firm I'm working for now tries to do as much as possible to avoid crunch," they added. "Even if we have to work hard for an extended period of time, we can always go to a special room with light music, comfortable sofas and comics. Producers try and get extra people on a team if they see things are going to be tough and, sometimes, features are removed in order to reduce the amount of work to do."

Another worker explained, "Currently the studio I'm at does a regular work to time review, so if a milestone is in danger we can revise time or man power to it. Crunch does happen but it's usually a few hours for a few days tops every few months. Far better." Someone else said, "[My company] removed mandatory crunch after feedback and usually planned things properly. They would also catch features that could easily snowball, make sure they were scoped properly, and constantly check on their status."

You'll notice that any attempts to rectify crunch woes are being out-weighed by the negative anecdotes. My interviewees had many varied stories to tell regarding crunch time horrors, and the perception of significant periods of unpaid overtime. Some of them admitted to working between 70-80 hours a week at some point, and were pessimistic when I asked them if things could change for the better.

This pessimism was one of a few things almost all of them had in common, despite coming from studios of various sizes and from different ends of the Earth. It's a grim consensus, but each of them contacted me in the hope of sharing their stories both publicly and without reprisal.

They also hoped that the decision-makers at offending companies would read their stories here, take a second to think about how they treat their employees and possibly consider reappraising their culture.

I'm not sure if that will happen, but this is an issue that needs to be discussed openly if it is to be addressed.

Over to you, executives.