Inside California's Secret Arcades

COVER STORY: With the arcade scene long since dead and buried, hobbyists are building private arcades of their own. We visited one.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In an unassuming neighborhood roughly 40 minutes south of San Francisco, there is a garage that appears to be part of your typical industrial park. You'd never know it by the look of it, but it's one of the last vestiges of what was once a thriving American arcade scene.

Every weekend, dozens of hobbyists descend upon this location to play Super Smash Bros. Melee, Guilty Gear Xrd, and a host of obscure anime fighting games. They are there to train, to play in tournaments, or just to hang out with friends. The tiny space is packed with arcade cabinets, tables hosting monitors and laptops, and players, many of whom spill out into the area outside of the garage to socialize between games.

In the back office is Myung Kim, the founder of what the community has come to call Gamecenter Mk. III. By day, Kim is one of many software engineers making a living in Silicon Valley. On weekends, though, he retreats to the space he created to play games, work on side projects, and spend time with other arcade enthusiasts.

What separates Kim's space from the various other "second wave" retro arcades and barcades that have cropped up around the country is that he's not looking to attract customers. Quite the opposite, actually: he'd rather keep his little slice of heaven away from the prying eyes of the public. He organizes events on a private Facebook group, declines to share his venue's location, and asks that any newcomers be vouched for by an established regular.

He's not the only one, either. Having accepted that arcades as we once knew them are dead, hobbyists are renting spaces or hosting events out of their own homes in an effort to gather with like-minded enthusiasts. This is the third wave of arcade fandom: the final resting place for an American industry that has long since perished, but still has plenty of survivors.

Why keep it secret?

I first met Kim in early 2012, when I profiled his arcade in San Mateo. At the time, Kim was trying to run an actual business, which he maintained in the hours after his day job was finished. His spare storefront had plenty of regular customers, but not enough that he could quit his job and run it fulltime.

"I was still working a day job and going at night and burning both ends of the candle, and in the end I decided I couldn't do this any more. It was personally taking way too much of a toll on me," Kim tells me as we sit together in his office. Outside, a tournament is raging, and every few minutes a player wanders in to either offer a donation or ask that the vending machines be restocked.

Many of the regulars at the tournament are veterans of the original Gamecenter. Others are friends who came in later. When Kim decided to get out of the arcade business, they were the ones who convinced him to try again with a more private space.

Kim's plan when he closed down the original Gamecenter was to store the games in an industrial space until he could liquidate them. But it wasn't long before he was getting Facebook message from old customers asking if they could keep playing. "I told them they could come over, we got pizza, and everything was fine. That really opened up my eyes a bit because it made me more acutely examine where I was spending my time and money and my stress at the old Gamcenter. And the bulk of it was because I didn't know who was coming in there. Because I didn't know who was coming in there, I either had to be there, or someone I trusted had to be there. Which meant either a bunch of time for me, or paying an employee to make sure people weren't messing things up. And when it's taking a lot of your time, you need much more return to make it worth it."

"But if you cut those two things out, all the sudden your overall costs drastically reduce. And now, if you just pay your bills, that's alright. I end up spending a bunch of time here anyway just because I like it, but I don't have to. If I want to meet my friends for dinner on Saturday night, I can totally do that."

The result is a space that works because of a certain degree of mutual trust. Every single one of the roughly 120 or so regulars at Gamecenter Mk. III understands the intrinsic value of the space; and they all know that if it were to go away, they would have nowhere else to go. In a very real sense, it's their home. "I appreciate that." Kim says, "I thank my lucky stars every week that happens."

Kim's desire to maintain that level of trust and mutual respect is what has led him to avoid publicizing his events and to keep the location's address a secret. I learned of the new space in part because I stayed in touch with Kim following my first story, his original Gamecenter being one of the only venues to support the Gundam Versus series at the time. I've since kept tabs on his community as they've moved from San Mateo to San Carlos, and now to their current location.

As with the original business, Kim's new space is more or less treading water. He asks for a donation from anyone who is there just to play on the machines, but tournament entries are free to encourage participation. Sometimes the income generated from the community isn't even enough to cover the rent for the space, and Kim has to dip into savings. It's fine, though, because Kim isn't looking to build a business - he's looking to foster a community. And at Gamecenter, he has one.

The anime fighting game dojo

One benefit to being a private club of sorts is that Myung can focus on much more niche games. Outside of Guilty Gear Xrd, one of Gamecenter's most popular games is the obscure fighter Under Night In-Birth, colloquially known as UNIEL among its fans. UNIEL is the spiritual successor to Melty Blood, itself known as "the most poverty of poverty games" in the fighting game community.

"Melty Blood is the game you shove into the hallway. It's the game that has its grand finals in the parking lot. It's become a meme for being the most poverty of poverty games. At Northwest Majors, they literally had the tournament outside, and the only free outlet they could find was by the trashcans," Kim laughs.

Games like UNIEL have found a home at Gamecenter in part because they jibe strongly with Kim's own interests. He was originally inspired to start his own arcade by a trip to one of Japan's arcades, colloquially known as game centers, which served as his business's namesake. He shrugs off the disdain that the fighting game community tends to have for pure anime fighters, "[Gamecenter was] anime fighter central. And to this day, I don't feel bad about that. It needs its own home, especially in the U.S. Street Fighter has plenty of homes. Everyday you can go somewhere in San Francisco and find Street Fighter. It's really hard to find places that play anime fighters; and even today, we are the premiere spot for anime fighters. We are the longest running event for anime fighters."

Gamecenter's unique focus has attracted a crowd that has had a hard time finding a home elsewhere. One of the venue's regulars is Filip "2GB Combo" Koperwas, who is one of the top UNIEL players in the country. Kim notes with obvious pride that Koperwas defeated the game's Japanese champion; and that when it was all over, his opponent admitted that Koperwas had played basically a perfect game.

He's not the only high-level competitive player who frequents Kim's spot. Regulars include GC Yoshi, who frequently places highly in events he attends, as well as top Guilty Gear Xrd players. "It's really cool to be able to say that if you come in here you will play against people on the U.S. champion level," Kim says.

Kim fosters Gamecenter's competitive scene with regular tournaments such as Caliburst and Dogfight, where the prizes are "guts and glory" and the chance to play against high-level competition. In some ways, it feels counterintuitive to run an event and keep it a secret, but Kim sees it as one of the key differences between his spot and the average tournament.

"It depends on your definition of success. A lot of time, a tournament organizer's definition of success is how much money in venue fees they can make. That is a very different definition of success than I have," Kim says. "For them, the more people who come, the better. And having high-performing players who come in regularly is a means to an end of getting as many people in the door as possible. I have a different definition. For me, it's basically fostering good players, making good players great players, and making the great players into world class players. That's my definition of success, and we succeed really well in terms of that."

The tournaments are run in part by Fred Lee, who Kim refers to as his 'right-hand guy.' According to Kim, "If I were to die, he would be the one to open this place up. He would become the new me." Like many Gamecenter regulars, Lee's former home is Sunnyvale Golfland - the legendary arcade known as the birthplace of EVO and the cradle of the fighting game community. It still exists, but only as a shell of its former self. When the Golfland scene died, Lee moved to the original Gamecenter, then followed Kim to the current space.

"It's really cool to be able to say that if you come in here you will play against people on the U.S. champion level."

Lee isn't alone - many of Kim's regulars are Golfland refugees. David Huynh, for instance, is a tournament organizer who has been involved with the competitive fighting game scene since the late '90s/early 00's. He was a regular at both the Milpitas and Sunnyvale Golflands. Of Kim's space he says, "I feel that having a reliable, consistent venue has done wonders for the NorCal anime fighting gaming community. I feel like I have seen the scene grow bigger and the average skill level increase because of it. I definitely feel like my game has improved because I had regular competition. Also, the scene has become much closer knit, so I have been able to build some great friendships and have had some pretty meaningful interactions with fellow members of the community. To me, Gamecenter is a comfortable place where I can mash as seriously as I want and hang out with friends in-between. From what I gather, our venue situation is different from other regional communities, many of which don't seem to have reliable spaces. I am thankful for what we have.

His comments are echoed by other fighting game fans who once called Golfland home. Gamecenter may not quite be a spiritual successor to that space, but Kim has been running successful events for several years now, and his venue has taken on a similar feel.

"I think [our tournament setup] works out really well for people. It rewires their motivations in a way to decouple their performance from financial gain," Kim says. "I think that's an important skill to learn: that playing your best and playing your hardest should be an intrinsic reward. If you need extrinsic monetary reward to play your best, it's not going to last very well. And because of that, I think we'll have some people who end up being lifetime competitors."

Hobocade and beyond

Kim isn't the only one running a private arcade space in California. When we were finished speaking, he put me in touch with Adam Karonika, who resides in nearby Sunnyvale. Karonika currently hosts a number of arcades in his home, all of them rhythm games like Dance Dance Revolution, Pop'n Music, and Beatmania, as well as a number of classic consoles on large RGB monitors.

Karonika refers to his space as "Hobocade," and says the space got its start in a one-car garage that he rented in Dallas. He elaborated over email, "We chose the name 'Hobocade' because a lot of our home version setups were improvised to be as arcade-like as possible (standing height, large CRTs) with whatever materials we could find for cheap (often involving cardboard in some manner). I hosted regular meetups for some friends of mine, word of mouth spread, and next thing I knew I was hosting a crowd of 20-30 people every weekend who wanted to either play DDR and such or just hang out and see old and new friends."

When Karonika moved to California, he brought his cabinets and sought out a larger garage for his new space. He says he's still getting acclimated, but that he's been hosting monthly meetups. Unlike Kim, he doesn't host tournaments; but at his last meetup, he hosted a high score competition for Panel De Pon (better-known as Tetris Attack).

Though their spaces have differing focuses, Kim and Karonika share a similar outlook on what arcades should be about. "I feel that most people don't see arcades as more than a place to play games, and are missing out on the social aspect," Karonika wrote. "It's common to strike up a conversation with someone playing your game of choice, or someone who sets an impressive high score. While online gaming has somewhat bridged the gap in meeting fellow players, the in-person dynamic of occurrences like crowding around an intense game and kibbutzing with random strangers, or asking the guy who just got off the machine for advice on a particular tough spot for you, cannot be replicated."

This is a common refrain among arcade enthusiasts: the sense of community that a shared space offers is irreplaceable. Fighting game fans will tell you that you can get a read on your opponent just by how they're hitting the buttons on a shared cabinet. That social aspect gets lost when playing online.

Japan is traditionally cited as one of the last bastions of international arcade culture; but even there, independent arcades are only just now waking up to the need to emphasize community over technology. The ones that have managed to survive are hosting daily streams on Twitch and Niconico, opening up their spaces up for events, and running regular tournaments.

"[Mikado] had a tournament, I kid you not, they had a vending machine tournament. Georgia Coffee had a limited edition Gundam can; so everyone got together and tried to buy out the machine," Kim laughs.

In what remains of the arcade scene in the U.S., though, community tends to get lost. Novelty is still the name of the game here, with many venues now being bars first, and arcades second. Kim rails at the poorly-maintained machines in Brewcade - a San Francisco-based establishment that has a great beer selection, but tends to treat its cabinets as a secondary concern.

"While online gaming has somewhat bridged the gap in meeting fellow players, the in-person dynamic of occurrences like crowding around an intense game and kibbutzing with random strangers, or asking the guy who just got off the machine for advice on a particular tough spot for you, cannot be replicated."

"I wanted to scream when I went to [Brewcade]. I was just like, 'Can you please give me the keys so I can open up this thing and replace the button because I know exactly what's wrong with this,'" Kim grumbles. "It's tragic because some of the games they have are actually kind of hard to find. But they're so poorly maintained that the experience is just kind of degraded."

Karonika echoes Kim's frustration, "It's rare to see an American arcade that stays on top of maintaining its games. With a few exceptions, most arcades I know let games sit around half-working or worse and don't take complaints from their players seriously. To an extent that influences people like me to seek out our favorite cabinets because the ones out in arcades aren't in top shape, which is a shame because it's not that hard to keep things running well. You can generally chalk that up to laziness or ignorance or some combination of the two."

The arcades that keep their machines in good order - Portland's Ground Kontrol, for instance - are lionized by the community, but they are vanishingly rare in this day and age. And it's even rarer to find a venue like Arcade UFO in Austin, Texas, which is modeled after the sort of Japanese arcades that Gamecenter seeks to emulate. Many are opened by hobbyists like Kim, then ultimately disappear when the rent gets too high or the founders burn out. Southtown Arcade, a tiny arcade that I profiled alongside Kim's Gamecenter, is one such example.

With that, arcade enthusiasts like Kim and Karonika are abandoning the business side entirely; not just to foster a communtiy, but for the sake of the preservation of the form.

Preservation

Arcade enthusiasts are remarkably attached to the old cabinets. They treat playing on an actual machine as something akin to a religious experience. It's not something that can be replicated, nor can it be replaced.

Kim discovered that firsthand when he asked the regulars at Gamecenter if they'd be interesting in shifting to console setups. They would be able to fit far more TVs and consoles into the space, he reasoned, which would mean more games to play. The response he received was a resounding, "No way."

"The tournament standard has moved on to something else, but there are a lot of people who value the premium experience," Kim smiles.

Kim himself is someone who values that sort of premium experience. When Gundam Extreme Vs. arrived on PlayStation 3 back in late 2011, he bought four copies of the game and housed them in arcade cabinets for a more authentic experience (the actual arcades need to connect to a Japanese ISP to function).

Kim's appreciation for arcades has also made him keenly interested in their preservation. He explains, "This is hardware that never had an intended duty cycle of five, maybe eight, years, and it's pushing two decades at this point. This hardware was not meant to last this long, and that it has is a minor miracle. When it does breakdown, it's so hard to find people who can still do the repairs. I had a CRT monitor that burned out. Who do you know who repairs CRTs?"

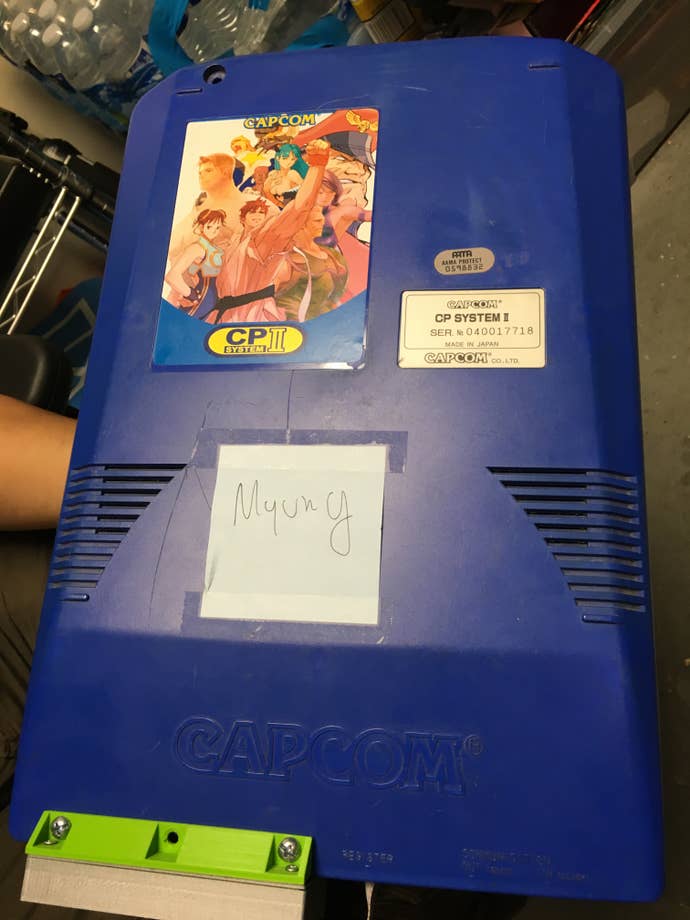

He picks up a CP System II board, the hardware that has housed everything from Super Street Fighter II Turbo to Alien vs. Predator. "Because this technology is old and breaking down and the new technology is getting cheaper, it's allowing us to modify some of this old technology. For example, this CPS-II... so normally the way games like this happened is that you had board like that with ROM chips stuck in. That was the data. But micro-controllers are so powerful and cheap now that, inside this CPS-II, you pull all those ROM chips out, you put in this micro-controller that has pins that fit in all the sockets, and it can pipe whatever data you want into the board. So you keep the original arcade form factor, but you just replace the data source."

As a result, Kim says, a CPS-II board like the one in his hand can hold every single CPS-II game ever made. And for the most part, it's thanks to the hobbyist community that these sorts of mods exist. Without them, many games may have already vanished entirely. And as Kim points out, even a port isn't enough in the hyper-dedicated fighting game circles. "All of these people have been playing these games in excess of 20 years at this point; so when a modern day port comes out, it feel terrible. It's all wrong. Because you have been inculcated over the past two decades on a certain standard. So in that way, especially for the older games, nothing can replace the arcade versions."

Going forward, hobbyists like Kim will have to work even harder to keep their preferred format viable. As arcades continue to fade, nostalgia is bound to fade with it. A 21-year-old in America today is unlikely to remember the arcade scene at all.

Kim acknowledges as much, "Arcades, as they are, are completely dead. If you visit Round One or Dave and Busters, you still get smatterings of current arcade games, but they are wrapped up in a 'family fun center.' They are very different from the older style of arcades. You can still kind of see the games, but the arcade culture is not there. They are monetizing off a very different model."

"This is hardware that never had an intended duty cycle of five, maybe eight, years, and it's pushing two decades at this point. This hardware was not meant to last this long, and that it has is a minor miracle. When it does breakdown, it's so hard to find people who can still do the repairs. I had a CRT monitor that burned out. Who do you know who repairs CRTs?"

He continues, "It's not an industry, it's a curio. It makes me sad, but I don't begrudge because there's plenty of other things that has happened to. It's not like they die. There's still hot rod meetups. There's pinball meetups; and not the stuff that you or I play, but stuff like solenoid pinball - the super old-school stuff with no digital displays. There are people who are diehard purists for this stuff."

If that's the case, then spaces like Kim's are apt to be how arcades are experienced going forward: private groups hosted by diehard hobbyists, or perhaps the odd museum. For now, they are a place for enthusiasts to come together in a way that has become increasingly uncommon in the gaming community and share their interests.

And it's not just the old veterans who are showing up. Jon Kbf is one of those aforementioned 21-year-olds who doesn't remember the halcyon days of the fighting game scene very well, but has nevertheless found a home at Gamecenter Mk. III. His own experience best encapsulates the appeal of such a space. "I was homeschooled from grade school through high school, and I was incredibly introverted and shy, so I often struggled to find people I related to. I struggled to find a hobby and a social outlet for a long time."

"Myung's Gamecenters have been one of the only places I can go to be around people who I knew shared my interests, people who have turned out to be wonderful, and were one of the first places I could eventually feel comfortable opening up, talking to people, and making friends."

Maybe not quite a new generation of arcade enthusiasts; but in the end, it's a start.