Indie kings – The Pickfords win with Magnetic Billiards

Following the release of their first iOS game, we sat down with John and Ste Pickford to pick their brains on 28 years in the business and how to outwit expensive lawyers.

The origin of the John and Ste Pickford’s first iOS game, Magnetic Billiards: Blueprint, is steeped in lore 123 years in the making. An aged, barely legible blueprint – the forgotten legacy of a long-dead ancestor - depicts the physical specifications of a wondrous machine with the potential to entertain patrons, but that was so volatile it might just have been the death of its creator.

There’s an alternate history, of course. One that speaks of an experiment begun some ten years ago with a Verlet particle system and the desire to teach a little girl to use a computer mouse by way pinging inanimate objects around a play area, but that’s nowhere near as romantic.

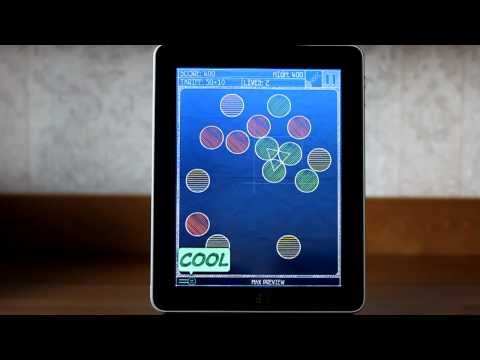

Whichever history you subscribe to, the result is a game with a simple premise: fire balls of various colours around a table with no pockets. Hitting balls of the same colour sees them cling together resulting in clusters and creating a big enough cluster will remove it from the table, awarding you points which contribute to you overall graded score for each table. Bonuses and multipliers are awarded for trick shots, as well as for the number of cushions hit prior to connecting with the target ball and for creating aesthetically pleasing cluster patterns.

It’s fun and maddening, as time and again you foil your own perfect run with a botched shot caused by a rush of blood to the head. Each improbably strung together cluster and shot of multiple bounces elicits a hand-drawn depiction of one of the bearded Pickford brothers giving you a thumbs-up. It’s a neat triumph of sound mechanics layered in charming, indie stylings.

Since releasing last month, the game has topped several iOS charts, including the UK sports league, placing above Football Manager. An accomplished first Mac outing for the Pickford brothers, then, but one that they were warned against making.

“We talked to a lot of developers to pick up tips for how to reach the biggest audience on the App Store,” Ste, the younger of the brothers, recounts. “And the majority of people we spoke to told us to make a different game: one with cute animals or without so much depth, and to knock it out in three months as that’s the only way to make any money.

“We’re driven to make the games that we want to make and I don’t think we’ve ever felt like those games are part of any current fashion. To be honest, we generally lose out a bit [commercially] because we’re slightly out of step with what other people are doing.”

Looking at the brothers’ development history through the all-seeing eye of retrospect it’s apparent that being “out of step” has at times equated to being quirky and at others, innovative. Wetrix, Plok and Naked War, none of which set the charts alight in their day, were all well received critically and will be remembered fondly by those that experienced them.

A question of convenience

Some 28 years of developing games gives the brothers a point of authority from which to discuss gaming trends. John believes the reason for the explosion of quality mobile gaming in recent years and subsequent creep into core-gamers’ consciousness can be succinctly summed up.

“It’s all about the convenience," he says. “The fact that you don’t have to go to it, it’s just right there - especially where the device is a phone so is something that you carry around with you all the time. That, plus a very simple purchase process coupled with relatively low prices make it just all very tempting. The convenience trumps everything, really.

“That said, there’s a lot of games that just don’t work on a touch screen – anything in which you control an avatar is generally disappointing with a virtual stick, so there’s a huge swathe of traditional games that aren’t really suitable.

“Personally, I love the challenge - which perhaps sounds really pretentious - but I love the challenge of designing a game that will work without those conventional controls. It’s fascinating to do that: to make a game that feels right and doesn’t make you think ‘I wish I had a joypad’.”

“Loads of devs bemoan the fact that certain types of games don’t fit these devices,” adds Ste. “Sure, [touch screen devices] exclude certain types of games, but they also open up new types of games too.

“It seems odd to be in the games industry and be a bit of a Luddite who doesn’t want to try new things. Most of us got into the games industry in the first place because games were fresh and new and different.”

Of course, the opportunity to be fresh, new and different along with the low barrier for entry has attracted a great many new developers to the mobile development scene. The challenge has shifted from simply making a good game to actually getting noticed amongst the cacophony of worthless tat and hidden gems that flood the App Store each and every week.

So, what master plan do the Pickford brothers have for combating the threat of obscurity? How do experienced veterans of the industry make their game stand out in the cornucopia of apps and rise serenely to sit far above the madding crowd?

“I was going to ask you that question!” responds Ste.

“This is our first iOS game so we’re still learning. It’s interesting because when you get noticed by appearing on a website or in a magazine you’ll see these spikes in downloads, but then it fades away over a couple of days so you’re constantly scratching your head thinking, ‘Bloody hell, we know that if we put this game in front of people there’s a good chance they’ll like it,’ but it’s possible to not get it in front of anybody if we don’t shout about it.”

“It’s the challenge at the moment,” adds John. “We’re no longer coding all day, now we’re trying to get people to pick up the game.”

Can’t buy me love

The lightening remains unbottled for now, then, but in searching for the magic formula the brother’s turned up some dubious practices by those claiming to have the answer.

“What came as a bit of a shock to me was people or companies offering varying bundles of five star App Store ratings for a few hundred dollars," Ste reveals. “We spoke to some other developers and they acknowledged that it does go on, along with the practice of paying for negative reviews for your competitors - it’s not a common thing, but it does go on.”

“One thing that’s worried me,” interjects John, “is that we’ve had really positive reviews on the App Store: we’ve got over a hundred five star ratings in a relatively short space of time and I was thinking that that’s our biggest asset, something that we can talk about - that people like the game - but after hearing about this I was concerned that people might think that the reviews are fake.”

“What was actually worse, though,” Ste continues, “is the responses we got from a number of websites that review iPhone games. The majority of responses that we received came with a price list for the different types of review that the site offered. So, maybe $30 for the small review, $50 for a video review etc. On most of these sites there was nothing to tell readers that the reviews are paid for. I was pretty shocked by that, shocked and depressed”.

Abhorrent as these practices are, they’re indicative of the well-publicised problems of a bloated mobile market and are just one of many challenges that indie developers face. John is quick to dismiss the notion, however, that the bulk of a major publisher standing behind you guarantees higher market visibility, regardless of the market.

“A few years ago, we worked on a game called Wetrix and right at the end of development the publisher decided that they weren’t going to promote it very much,” he remembers.

“As a developer beholden to a publisher, there’s nothing you can do about that. I mean, the game did OK and lots of people seem to remember it, but none of that was because of the publisher’s marketing budget. The game had a publisher and still didn’t get promoted.

“So, working without a publisher can be a challenge for indies, but it’s also an opportunity.”

“Working without a publisher is how we make good games,” declares Ste. “I don’t mean that to sound self-indulgent but when you work with a publisher you can run the risk of having the marketing budget but being constricted in what you make.

“Now, whether that’s because you have to include certain fashionable features or you have non-designer interference or whatever - you can find that you end up with the marketing budget but you’ve had to create a ‘me too’ game to get it.”

“Indie development lacks the committee-led design, I think,” ponders John. “With Magnetic Billiards we made all the decisions and every single thing that you see in the game is there because we’ve made a decision to put it there. So, good or terrible, it’s all our work.”

Stop, collaborate, listen

Something in the brothers’ approach is definitely working for them, and it seems their creative vision is now inspiring others. The brothers have begun receiving offers from developers looking to work with them, have them consult on projects or develop games based on their back catalogue.

“Something that I’m not sure we’ve mentioned to anyone yet is that Naked War is coming to iPad,” reveals Ste. “That’s as a result of working with another company who are coding it right now.”

“I think we made Naked War just a bit too soon,” John says of the turn-based game’s original 2004 release. “If we’d made it for Facebook I think it would have done well, it needed a friends list to add that social element. Naively, we thought it would work because there was an email side to it that would give it a chance of spreading virally but it didn’t work out so well because a lot of people thought they were receiving spam!"

“It’s not an unusual story for us: the people that played it, loved it - but we just had to find a way of reaching an audience ... With iOS 5 we’ll have a turn based mechanism built into Game Center and we can package the whole map, including the damage, into each iOS turn file which means we don’t need a server to run it.”

As we wrap up our discussion I ask in passing about the company name, Zee-3, and their previous studio Zed Two, commenting that one sounds UK-centric whilst the other could be construed as an effort to reach across the pond.

“The name is actually the result of a joke!” Ste laughs.

“We knew we’d be working with Americans so the spelling out of the word Zed was perhaps the first part of the joke,” John clarifies, before Ste resumes.

“We sold [Zed Two] to another company and they made us redundant. As part of the redundancy package they had legal documents drawn up by these expensive £250 per hour lawyers and, because at that point we had no money, we had no choice but to sign them.

“There was a clause that stipulated that we couldn’t set up another company called Zed-2 or that contained the word Zed or the number 2. It took the sharpest legal minds to come up with that clause and we duly abided by it: we set up a company called Zee-3.”

It’s this offbeat humour that makes indie development and Magnetic Billiards: Blueprint a refreshing place to be.

Magnetic Billiards is out now for iOS devices. It’s available for 69p with 20 standard play tables, £1.49 for an additional 20 more challenging tables or £2.49 offering all 40 tables plus 3 additional play modes and free access to all future content.