In Mass Effect, Shepard Never Gets to be More Than a Soldier

Mass Effect's militarism has aged like milk.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

"When you contacted me and said, 'I'm playing Mass Effect right now,' I was like, Mass Effect in 2020... That's weird," says Dr. Jordan Youngblood. Youngblood is an associate professor of English at Eastern Connecticut State University, where he does research into video games and gender and sexuality studies.

I reached out because I've been playing Mass Effect in 2020, and it has in fact been weird. BioWare's popular space opera trilogy is a favorite series of mine and one I've regularly returned to over the years. Revisiting old games is often a productive and meaningful undertaking that can reveal as much about yourself as it can your nostalgic, imperfect memories. But this latest deployment aboard the Normandy hit differently, and I needed answers.

Spoiler warning: This article contains spoilers for the Mass Effect trilogy.

Shepard's journey from a freshly-minted commander to a resurrected yet maligned war hero to the face of human persistence against total annihilation once felt good. Their constant skepticism of the de facto governance in the galaxy used to seem rational and justified. Their insistence that everyone help the Alliance Navy defeat the Reapers or else get the hell out of the way came across as righteous and necessary.

It would be a lie to claim I experienced a complete heel turn from these sentiments. Mordin's sacrifice to cure the genophage still hit hard, and I once again held my breath through much of the suicide run on the Collector's home base. But emotional investment in all my favorite characters could no longer distract from the pervasive undercurrent of military exceptionalism throughout the series. I was older, more cynical, and already discarding the last shreds of the politics adopted from my parents.

Mass Effect hasn't changed, but I have.

Jack Bauer or Captain Kirk

The writers and creative directors of Mass Effect have never been shy about their influences. The success of 2003's Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic and 2005's Jade Empire inspired them to adapt their action RPG formula to the tropes and trappings of hard science fiction popularized in the '70s and '80s.

Mass Effect writer Chris L'Etoile specifically mentions E.E. Smith's Lensman series, along with a number of crunchy role-playing systems such as Atomic Rockets, Attack Vector, and 2300AD. Other writers, like Chris Hepler, complement those interests with popular films and television. Despite a shared love of Star Trek, the team wanted to avoid recreating its vision of utopic egalitarianism. And like those genre mainstays, the developers wanted Mass Effect's protagonist to have largely unfettered access to the entire universe and carte blanche regarding their actions and decisions.

"Giving the player government authority in the form of military rank was an easy explanation for getting a ship, a fully-loyal crew, and a resource base at the outset," says L'etoile. A writer for Mass Effect 1 and 2, he was responsible for worldbuilding and companion writing. Most recently, he helped create the character of Parvati Holcomb for Obsidian's The Outer Worlds. "Going one step further and inventing the Spectres was a quick handwave to extend that authority across the galaxy."

Commander Shepard as a Spectre inherited more than just a wisecracking crew and plot armor from the DNA of '80s sci-fi cinema. That exceptionalist mindset grafted well onto the power fantasy framework of RPGs, necessitating a world in which the threat is always real and the player character is always the only one with the ability, or determination, to stop it.

Dr. Youngblood believes this sounds distressingly close to the rationale of 24, perhaps the best representation of popular media in an immediately post-9/11 America. Main character Jack Bauer, like Shepard, operates with extra-judicial authority for the ostensible good of the country. And despite the warnings and doubts of the government that instated him, Bauer's gut feelings always play out as the right choice.

Indeed, the Mass Effect writing room looked to 24 as inspiration for its adaptation of Knights of the Old Republic's Light/Dark binary morality system, which would eventually be codified as Paragon and Renegade.

"The archetypes we were told to follow for Shepard's dialogue were Captain Kirk of Star Trek for Paragon and Jack Bauer of 24 for Renegade," says L'Etoile. "Kirk always takes a morally upright path, and somehow makes it all work out... even if that requires reprogramming the Kobayashi Maru simulator. Jack Bauer does morally questionable things because he knows 'there is no other choice' to save lives. In the game, both options must lead to successful outcomes."

There is no question of success for Shepard the Spectre, just as there is no question of whether or not Kirk or Bauer will succeed by the end of the episode. Players may fail a combat section, but they will never fail to stop Sovereign from gaining control of the Citadel, or prevent the Reapers from converting all advanced life into genetic slurry.

"If Mass Effect turned out to be Shepard saying, 'You know what? I'm actually going to trust in the overall mechanisms of the larger nation state of which humanity hopes to be a part,' and it works itself out over time; the systems work the way that they should, and Saren is routed out and Shepard slots into a job within middle-level bureaucracy, right?" asks Youngblood. "Who the hell is going to play that? But, hey, the system's fucked. Nobody's listening, but you know the deal. That's exciting."

The Exceptional(ist) Soldier

Over the course of Mass Effect's three-game narrative, Shepard is meant to embody the best attributes of the Alliance Navy: proactive, charismatic, and acting in defense of everyone's welfare. That they are the ideal soldier never creates friction with their status as a member of the galactic government's secret wetworks program. Captain Anderson, the series' mouthpiece for the Alliance, views it as a natural progression of Earth's place among alien society.

But humans are not the ultimate military power in Mass Effect's universe. At least, not at first. The writing team wanted to side step reductive tropes of alien cultures either being "angels or cavemen" by positioning Earth as the ambitious underdog new to galactic politicking.

"Even 15 years ago, I considered that aspect of the Mass Effect setting a direct and needed antidote to the unacknowledged attitude of 'human exceptionalism' that pervades much of science fiction," says L'Etoile.

The other established species criticize humans for being too young, unproven and ill equipped to handle the responsibility of Council representation. Yet, it is not the ambassadorial work of Donnel Udina that eventually persuades the Council. His relationship to the player is characterized as adversarial; a bureaucratic waste of time while the enemy is out there getting away with their scheme. Humans quickly shed their place at the bottom of the list thanks to Shepard's ceaseless pursuit of justice, the ultimate display of which is seeking out and neutralizing an external threat to peace and prosperity.

Saren fills the classic role of rogue agent for the new recruit to track down and eliminate. Not only does this erase the largest argument against a government managing a cadre of agents with license to kill, it re-establishes a moral framework upon that system that is more palatable to the player who envisions this world. Saren was not wrong for killing entire colonies and appropriating ancient artifacts. He was wrong for doing all that outside the express orders of his superiors.

"It feels like games (and most art in general) that try to enact heroism routinely fail because of the lens through which they are trying to manifest 'justice,'" says Dr. Christopher Patterson, an assistant professor in The Social Justice Institute at The University of British Columbia. "I don't fault Mass Effect or any of its makers for 'failing' in this sense, as what is interesting to me about the game is how it reveals the faults within our own ways of envisioning 'moral righteousness.'"

Hegemonic power creates and reinforces reasons for its own existence, often through the arm of a military apparatus. I celebrated my ability to convince Saren of his deep indoctrination at the hands of Sovereign, which leads to him taking his own life in a rare moment of true lucidity. It did not occur at the time that I celebrated one moment of not physically pulling the trigger myself. Every promise made and fulfilled was done with three guns strapped to my back. Even as a member of Cerberus, my actions carried the weight of a private military company rivalling any other galactic force.

"I mean, in order to make the RPG power fantasy work, you kind of have to say f**k you to socialism, or to any system that works. Because that's a distribution of power," says Youngblood. Nobody comes into contact with Shepard unchanged. They either leave with a newfound respect for the best the Alliance Navy can produce, or with a spent thermal clip at the foot of their corpse.

Dr. Patterson sees the Alliance Navy, which for all intents and purposes mirrors the American military on a global scale, as portrayed aspirationally. Race, gender and sexual orientation do not preclude one from service, and though Ashley Williams reminds players that a tiny fragment still hold a xenophobic torch, the vast majority accept life in a multiracial society. But even that idyllic version perpetuates the same system of justification as our real world counterpart—"the violence that this military causes will always cause collateral damage, will always backfire to create more enemies," says Patterson.

No Room For Messy Ideas

"Part of the glossing-over of Earth cultures was the result of an informal agreement between myself and Drew [Karpyshyn, lead writer for Mass Effect 1 and 2]," says L'Etoile. "He believed that humanity would progress in the optimistic way Gene Roddenberry anticipated—that over time nations would amalgamate in the manner of the European Union. He felt there would be fewer nations on Earth in the time of Mass Effect and a more unified global perspective brought about by entertainment monoculture and the ubiquity of online interaction with those of different perspectives."

Before joining the Mass Effect writing team, L'Etoile had worked in MMORPGs and witnessed a culture of harmful behavior towards other players, from doxxing to stalking and constant bigotry. He watched global politics enter a decade of bloody secession movements, occupations and balkanization. Contrasting Karpyshyn's optimistic vision of the future, he saw humans only becoming more siloed and insular in their beliefs and treatment of others.

"Since we weren't planning to present Earth in the game, it didn't seem worth the effort of arguing over it. Drew and I just set the matter aside," he says. "I'm not happy to be winning the argument in 2020."

Earth, as portrayed through the Alliance Military, is largely homogenous. Differences in skin color and hair type are cosmetic choices during character creation, and all human lines are delivered with an accent similar to the General American English adopted by television news reporters. Hepler tells me NPCs were assigned a surname from one culture and a given name from another to help sell the idea of Earth as a futuristic society. It "hinted that it's 200 years from now and there was a lot of cross-pollination that happened in the interim."

Earth also exists outside the player's reach for the majority of the series. In both Mass Effect 1 and 2, you can see it within the Sol System as you bounce across the Mass Relays that serve as intergalactic transport lanes, but it never serves as anything more than a novelty (though you can extract resources from our solar neighbors). Your Shepard might have no connection to Earth at all if you chose for them to be born a spacer or on one of humanity's first colonies.

The rare exception to this cultural monolith is Lieutenant James Vega. Played by Freddy Prinze, Jr. and one of the only recruitable humans of color, Vega conveys the strongest ties both to Earth and a life there before the Reaper invasion. He is in many ways a foil to the Shepard of Mass Effect 3: naive, hotheaded, and largely apathetic to the fate of anything beyond Earth. His interactions with the player character serve to remind them of what they are fighting for; it would only be a small leap to imagine Vega on recruitment posters with phrases like 'Be All You Can Be' emblazoned underneath.

But his brownness rarely goes beyond a peppering of Spanish phrases and a large dose of machismo. Any cultural signifiers of his life on Earth have been sanded down to fit inside an Alliance Navy uniform. We see a similar tolerance in the American military, whose Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy forced soldiers to keep any deviation from the popular image of a soldier to themselves, lest it become a problem. Vega can be a proud brown man, as long as he is also proud of the N7 tattoo on his back. "The game shows us our own logics concerning militarism and power, how we can allow violence to be permissible so long as there is a form of tolerance and inclusion that comes with it," says Patterson.

The choice, then, to focus the culmination of the trilogy on protecting and avenging Earth reads to Youngblood as a course correction after the interesting thematic complexity of its immediate predecessor. "Mass Effect 2 is the weird, queer outlier of the series because it has no idea what the hell it's doing," he says.

Predicated on the death and rebirth of Shepard, Mass Effect 2 takes many of the sociological assumptions of the first games and twists them, where it does not outright question their existence. The Council government has whitewashed your victory over Seryn to keep the populace from panicking; your "death" provided a neat period for that sentence in the history books. The agent of change and proactive justice is the ethno-military Cerberus, and your found family of societal rejects and rebels try their best to ignore that fact even as they sign up for a suicide mission.

These and other contradictions provide players a chance to pick at the status quo established in Mass Effect 1. It is a game of tantalizing 'what ifs,' even if still painted in a comfortable veneer of squad-based shooter combat. Alien companions can act less like the sole representatives of their species. If only nominally, the Alliance Navy has their actions and motives called into question. That same loosening of restrictions allowed developers to double down on troubling facets of its own narrative.

"Mass Effect 2 is where the series, narratively, becomes interesting—no longer are we in some faux-idealistic Star Trek-like multicultural alliance, but we're in a species/ethno-military led by a corporation whose leader is interested only in exploiting crisis for human domination," says Patterson. "Mass Effect 2 to me is delightfully perplexing and in many ways very true to what American militarism in its most heinous moments represents—a form of white, religious, and cultural supremacy masking itself as mere security that legitimates its violence by convincing anyone and everyone to collaborate with their project to their point of their own deaths."

Each companion's loyalty missions, which are treated as a prerequisite for their ultimate survival, sees you either earning their trust or demanding they fall in line. Empathy and understanding are means to the mission's end, a tool for increasing the chances of operational success. Even the queering of a game and its characters can work to reinforce the insistence that military power used ostensibly to save lives is, at worst, a necessary evil. Shepard's found family may justifiably die to provide a step up to punch the bad guy in the eye.

By Mass Effect 3, any trace of previous deviation, regardless of its intent from established norms, had disappeared. "Our mission statement was 'write some of the most emotionally engaging games in the world,' but that's not the same thing as a revolutionary story. We aimed at a genre story," says Hepler. "The leads wanted a familiar story with good execution rather than something experimental that might win a Hugo or Nebula but not sell a bajillion copies."

The Only Choice

Mass Effect 3 exemplifies the military exceptionalism at the heart of Shepard's character in its opening moments. After being released from confinement for joining a terrorist organization in the last game, Anderson tells the player to consider themselves reinstated. There is no hearing. There is no accounting for crimes, even if they were committed with noble intentions. Besides, you never got too friendly with that Illusive Man, or it was all a ruse to undermine him.

"The beginning of [Mass Effect 3] is basically every conservative's wet dream," Youngblood says. "You show up in front of the collective government and say, 'You were all sitting on your asses. You thought it was peacetime, but really the enemy is on our doorstep, and it was bigger than you could have ever expected. And it's even here among you."

And before anyone in a position of representative power can object, a Reaper invasion arrives and kills anyone who might have done so in the first place.

Youngblood argues that, of course, this had to occur. Mass Effect 1 proved the success of BioWare's action-RPG model, prompting EA to get involved and pump plenty of resources into a sequel. Securing the success of a third and final entry meant solidifying production and iterating on what players wanted: bigger guns, badder bosses, more of everything.

"The joke used to be that if you were reading a novel, like a queer pulp novel, in the 50s or 60s, what you did is you read everything up to the last chapter," says Youngblood. "And then you stop, because the last chapter always fixes things back to the way they 'should be.'

It is easy to dislike the shouted proclamations that characterize the end of the trilogy. Loud, both in emotionality and presentation, Mass Effect 3 traded a desire for asking interesting questions for a podium and a bullhorn. This can feel good when the game allows a poignant moment with nearly every surviving character; when all the companions double down on their convictions or offer a word of thanks for helping them realize the fullness of their character. It also delivered an ending where Shepard listens as Anderson and the Illusive Man, nearly an angel and devil on their shoulders, state the case for their own righteous idealism. Intentionally or otherwise, the game tells us the Illusive Man's one unforgivable sin was acting outside the control of the military.

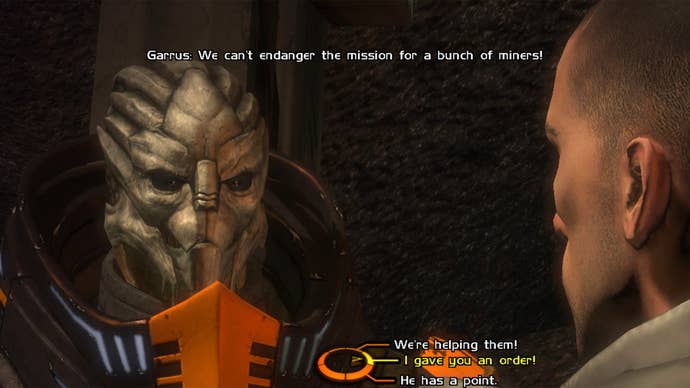

L'Etoile and Hepler say Mass Effect was meant to "tell an exciting military space opera trilogy in an updated style from the late 70s," but the disappointing realization is that it lacks the ability to tell any other kind of story. The Paragon/Renegade system reduces morality to a system of conditional flexibility, which Youngblood views as an eerie precursor to online discourse in 2020. Patterson calls it a "decision to woo one's teammates, to keep them happy and less inclined to betray you later."

But even that gripe springs from a foundational assumption made back in the Council chambers on the Citadel, later fully-realized in conversation with the ghost child on the Crucible. Shepard is stripped of their armor, squad and abilities, essentially everything a player could choose to define their Shepard. They are left with the essence of the immutable qualities they had no choice but to accept from the start: a soldier, a Spectre, an extension of the military, an exceptional actor on the galactic stage deciding the fate of all life for themselves.

Shepard is allowed to care and listen, to love and be loved, to change the universe from a place of empathy. But ultimately, the only Shepard that matters has a gun and a mission. I don't have the stomach for stories like that anymore.