"I Don’t Know if a Duck is Going to Swallow me Whole." The Tim Schafer Interview.

Tim's history, career – and the ups and downs of game development and crowdfunding.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Tim Schafer needs little introduction. Veteran LucasArts designer of some of the most beloved point-and-click adventure games of all time, and President of Double Fine Productions, Tim has become one of the most well-known personalities in the games industry.

I sat down with him at his San Francisco office to talk about his history, career – and the ups and downs of game development and crowdfunding.

Let's start at the very beginning. What’s your earliest video game memory?

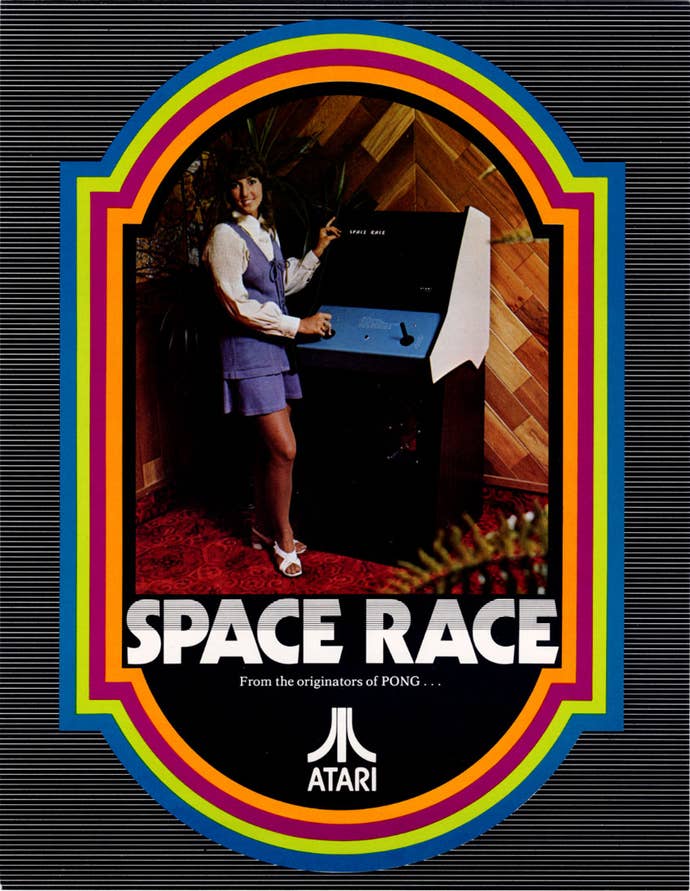

"The thing I always think was first was at summer camp - Blair Camp Blue. In the lodge, there was a standup arcade machine called Space Race that no one ever talks about. It was a vector graphics game where two spaceships are racing up the screen and there’s a horizontally-moving field of asteroids."

"Another really early memory: I remember being on a ski trip with my family and there was a pizza place where they had Atari Stunt Cycle. There were actual motorcycle handlebars that you had to use to jump this little guy. They also had an Atari Night Driver machine. I loved Night Driver. It looked 3D and the way that a road really looks in the distance. That was all so new, to see a computer creating a three-dimensional effect to parallax. It was so magical and exciting."

"Another thing that really impacted me at the time was on Pier 39 in San Francisco. They had a huge arcade that had Space Panic, which was a Lode Runner-type game where aliens would come after you. You'd have to dig a little hole and the alien would fall into it. If you quickly buried it, it would die. That’s horrible! [laughs]. More people know it as Apple Panic because it was on Apple. You could also run out of air and, "Oh my God! This is horrifying!" It was great! But when I was playing it, I heard this sound, "Thump, thump, thump, thump." My Dad said to me, "You have to see this game. It’s called Space Invaders.""

"So, there's a mish-mash of games that I consider my earliest memories: Space Panic, Night Driver, Space Invaders, Space Race. Those are my first arcade memories. All of them are tied to my Dad. He was really interested in this stuff and he always dragged me along. I was always the one most interested in all of that. One day, he brought home Magnavox Odyssey and it was just like, "Oh my God…" Everyone played it at first; my sisters, my brother. There are five kids in my family. We would just open that thing up and we were playing the Pong game, of course."

"The thing I loved was you put the graphics on the screen with an acetate sheet that would stick with static electricity to your TV. Then you would see every game was a version of the Pong game, just with different rules. A lot of times, it was up to you to maintain the rules. It's crazy to think of now, but I just loved that an old CRT monitor with a Pong paddle on it. It would glow through the colored plastic in a certain way. I still remember that feeling of the glowing screen."

"I don’t know what it’s like for kids when there were already games, but I just remember there not being games, and then there being games. That was so exciting for me. My older brother was nine years older than me. My parents had a kid every other year and then there was a four-year gap, and then me. Whenever I wanted to play Sorry or Chutes and Ladders or whatever, they were like, "That game’s stupid." They wouldn’t play games with me and I just wanted to play all of these kid games they wouldn’t play. Then video games came out and I was like, "I can play these by myself. I don’t need my brothers and sisters to play with me." There was a funny connection between being solitary and video games that then comes all the way around to nowadays where video games are a social thing for me. They pulled me out of isolation."

"Then my Dad brought home an Atari 2600. That was another magical experience for me. It was called a Video Computer System back then. It came with Combat, Surround, and Air-Sea Battle. I was always hypnotized by it. We played Combat, a game with airplanes, and when the game was over, it would just go into an attract mode and just go through random color cycles, which I feel like defined hipster graphic design 30 years after that; all of a sudden everything was these colors that Combat would turn into. I would just sit there watching the biplanes go through the clouds and watch the colors change. There was a time when new technology just feels really magical to you. I would still probably enjoy playing one now."

"I was thinking about when the first 3D polygonal games came out, it just felt magical to be in three-dimensional space. I remember in Alone in the Dark, which was a zombie game. There was a monster bashing on the bedroom door and you can see it through the cracks of the door coming at you. Then you can go out in the hallway and look down at the same door and see the same monster from the side. They didn’t have to paint a new direction; it just was being shown from a different angle. It felt like it was alive and real because it was 3D! Nowadays, that is not exciting. Seeing a character from two sides, you don’t care at all. It doesn’t impress you. It does not feel magical at all. It’s too bad that that stuff is so transitory because you can’t really recapture the magic of when new technology comes out and it just feels like it’s crazy.

I wonder about that with VR. Now that we’re all looking in VR, there is something magical about being in that space. You put on the glasses and all of a sudden you’re sitting in a forest. It’s crazy. I wonder if that’s a permanent feeling? Or if that’s one of these new technology "glows" that just feels really magical and in five years it will not feel magical. I mean, we’re still playing video games and a lot of the time we demand that it be 3D. It’s not like we gave up on that, it’s just that that really exciting feeling of something that’s like magic…"

Did any of those earlier magical experiences inform your career in games design?

"A lot of those things stuck with me. Another really formative thing was just begging my dad to get the next Atari cartridge. It was a huge thing because it would just take so long to get the next one. I had a dream once: I woke up in my bedroom and I was dreaming that I was looking at every single Atari cartridge ever made in those beautiful rainbow boxes. It was laid out on my floor because I dreamt that my dad had gone and gotten them all and just put them there. I just remember slowly opening my eyes and watching them just vanish. They drifted away. It was like pulling teeth to get him to get the next one."

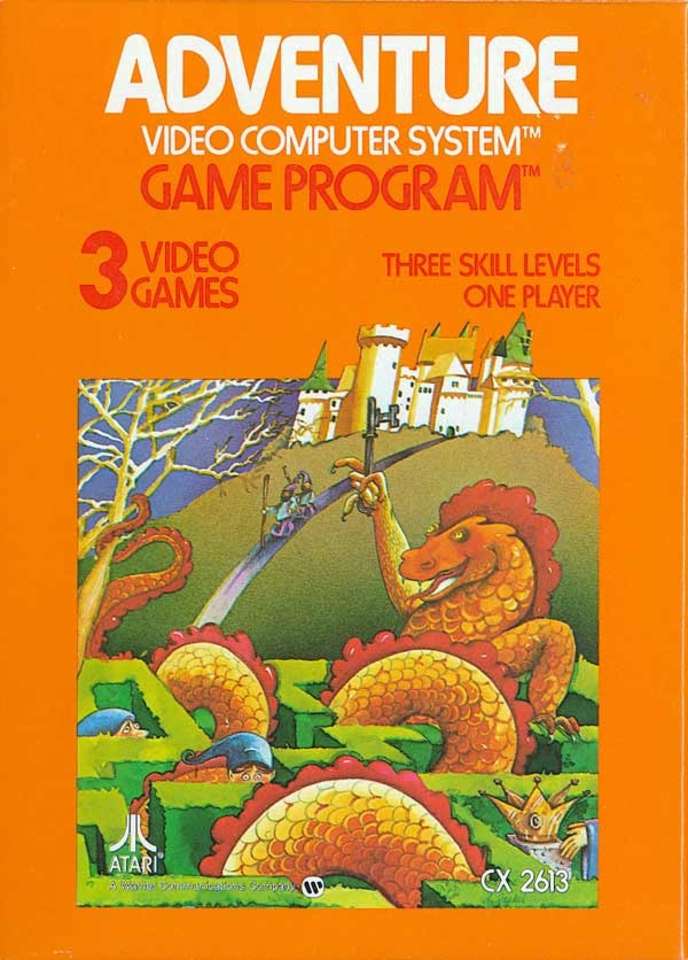

"Once, I convinced him to get a game, it was an Adventure cartridge. I was so excited I just ran out of the car and tore open the box and just started playing. I didn’t read the manual at all. I was like, what’s happening? I’m a square? There was an arrow and there is a horned cup and a castle and a duck is attacking me. I just remember how confused I felt, but also excited as well as confused. I was so happily confused the whole time that I didn’t know what was going to happen next. To me, that’s always stuck with me as something I really enjoyed. Sometimes I feel like I rely on that too much in games. I expect everyone to be as delighted by being as confused as me. It’s not often that other people find it as pleasant as I do. I love when I feel disoriented and confused and I am in world where anything can happen. I don’t know if a duck is going to swallow me whole. They were dragons, of course, but I love that feeling."

That sort of feeling of confusion and what to do next is part and parcel of your early adventures – where you’re moving from one puzzle to the next, and you have that space where you're basically letting the player become confused, so they can figure out what to do next. Is that a common theme to your game design?

"Yes. I think that there’s a challenge with adventure games that not everybody enjoys, but the people who do enjoy it, enjoy it a lot. It's the well crafted, entertaining confusion – that is, can we confuse you in a way that is still delightful to you?"

"That’s why it takes so long to design and make an adventure game. That’s the frustrating thing about it. You’re kind of crafting this mental path for the player. They’ve come to a ravine, and they can’t get across it. You have to plant the idea that they want to get across it. There’s a door on the other side of the room or a cave or something. So you’ve built this desire to get across the ravine and there’s a ladder in the room. So, you think the next link they’re going to make is to use the ladder to get across the ravine. So you purposely make the ladder too short to cross the ravine. They have this moment of, "A-ha!" and then they’re denied. A few of those ups and downs and then they figure it out. If the ladder just worked, it would be super boring. So the ladder can’t work, but the ladder can help you get up to a shelf you didn’t notice before and on that shelf is a rope. The rope can be put through these pulleys and these pulleys can help you lower yourself down the rope into the ravine to find another piece of ladder. So for me, what I like is that at some point, you have to use a ladder in a way that no one uses a ladder. You have to use a ladder to hit a bear over the head or something. You have to use one of these objects in a combination it’s not meant for or in a combination that doesn’t make sense. The opposite of the obvious solution often turns out to be the one. The door that you think you have to pick the lock on or break into, you actually have to weld shut. Or something like that. Counterintuitive, lateral thinking they call it. One of the steps at least has to involve some of that."

"You’re putting these little stones in a pond hoping someone will jump from one to the next one across the pond, but sometimes they just can’t see the next stone. You put it right in front of them. You put a sign pointing to it, but they just can’t see it. They're stuck, and they end up hating the game. They can instantly get very, very mad. And hopefully they’re not a game reviewer because at that point, you’ve just lost it all. So to solve that, you get another character to come out and say, "There’s a stone over there," and they player is like "Oh, ok." However, you’ve removed the entertainment by removing that confusion. It’s not entertaining to just execute a series of solutions. That’s the whole point of adventure games, happy confusion. If you have given the answer, you’ve taken that away from the player."

"When you’re doing playtesting, the people who are really watching the schedule, producers or programmers, are like, "Look, we just really have to get this done, so just put a sign that points to the next thing." Well then I’ve taken away a big chunk of the entertainment from the player. That’s something that we’ve invested a lot of money in; to have this pond and these stones that look really good and we can’t just take that away. You’re devaluing the game, but then again, if you don’t put something in, then no one finds it and they’ll hate it and write a bad review about it. So, it’s a fine line to walk. It’s the tough part about adventure games."

How do you test those puzzles?

"We bring people in and we watch many, many people play the game and we’re really, really quiet. We’re not allowed to talk to them – unless there’s a bug we need to explain. We just see what they do and then we debate afterwards, how to respond to it. We don’t do a numerological, scientific approach to it, but we just look. Imagine someone had bought the game and was playing it; how would you feel if this was their experience? There’s a lot of debate. And there’s an art to it. How do you respond to that kind of feedback. A whole book could be written about that."

I wonder whether Tim has ever had "bad confusion" in a game that he's played.

"It’s interesting, because I was describing things that I liked, that pleasant confusion thing, and I think that’s what a lot of people talk about when they talk about how they liked the first Zelda game or the third one. They talk about how wide open it was and you need to figure out what to do. I think it’s a very similar story. And then we went through a period of games in the early 2000’s where we went through every doctrine of tutorialization. Not that Microsoft was the only one doing this, but we were working with Microsoft at the time. You know you’re dealing with a company that makes products for people that they expect to use, like Word or Excel. If they can’t use that, they’re not getting their value for what they paid for. So you have to make sure that everyone knows how to enter values on a spreadsheet and do formulas or someone’s going to get really mad."

"I realized that when they were testing the second Psychonauts, they were doing so in the same kind of usability way: "Well no one knew what to do here." I was like, "What do you mean?" We tested out the Black Velvet level in Psychonauts. They said, "Well, it was good. People liked it and had fun, but there were periods where they were confused and they didn’t know what to do." I said, "Did they get stuck on the magic paintings that come to life when you hang them on the magic hook?" They were like, "Yeah, yeah. They have the paintings and they didn’t know how to hang them on the hooks." I was like, "Oh no - but eventually they did figure out how to hang them on the hooks, but they didn’t know which hooks to hang them on." They responded, "Yeah. Well, they tried them in a few different places and they eventually figured out which hooks to hang them on and then they got through it." I was like, "You just described solving an adventure game puzzle to me". All of those steps are the correct steps. What do I do with this inventory item? Let me try it here. That does something, but that’s wrong. Then you move it around in a new combination. Oh that works. Perfect!"

But the response was, "They were confused for a while and that's bad." But that's the point of the game! It's not bad, I think it’s good to be confused for a little while."

"I just remember an important person at Microsoft telling me, "There are winners and losers out there. You should make the game for the losers because there’s a lot more of them." And I laughed and I thought that was really funny. However, I feel like there's a current reaction to that, whether people are playing Super Meat Boy, Spelunky or Bloodborne, there’s a certain nostalgia for not knowing what’s going on all of the time. Not being told what to do. Having to figure it out. Even though those games are really hard. I think that’s a reaction to that period from 2000-2005 where things got a lot more tutorialized."

"One thing I love about the first Tomb Raider game is just standing in a tomb. You know you want to get up really high to this upper ledge, but there’s no way up there. There’s no ladder or anything. There’s a little crack in the wall. I can follow that crack to that pipe. Oh wait, I can probably climb that pipe… I just remember playing Uncharted (which are great games) and I was in this temple, and I had that feeling of, "Oooh, ooh, I need to get to the top. How am I going to do it?" Let me think about it. Right when I was thinking about it, "Press against post and Press A…" this text came up and told me exactly what to do. I just felt so cheated."

"I know they tested it and the feedback came that people were angry because they couldn’t figure out what to do in that temple. So, who do you please? The winners or the losers there? There’s an art in trying to meet that dynamic. Waiting a certain amount of time. That’s what we do a lot in adventure games too. How many times do we let them fail before we give them a hint? We debate that back and forth a lot. So how long should they have to stand in that temple there before you have to put up that text? In my case, it was a little too soon. Getting that right is always a challenge."

Up next: Tim's early career, the development of The Secret of Monkey Island and Full Throttle, and how he never actively sabotaged Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire.