"I actually was hunting Ewoks." The Original Lucasfilm Games Team Talk About Life at Skywalker Ranch.

Booger Hunt. George Lucas avoiding tax penalties. Monkey Island and dependency charts. The Lost Patrol. A file drawer full of crazy ideas. This is the story about life at Lucasfilm Games - as told by the people who lived it.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Back in late 1985, when I was still a very junior reporter on a British Commodore 64 magazine called ZZAP! 64, I was handed an assignment so plum, I didn't actually believe it until my boss showed me the letter confirming it. And even then, I was still incredulous.

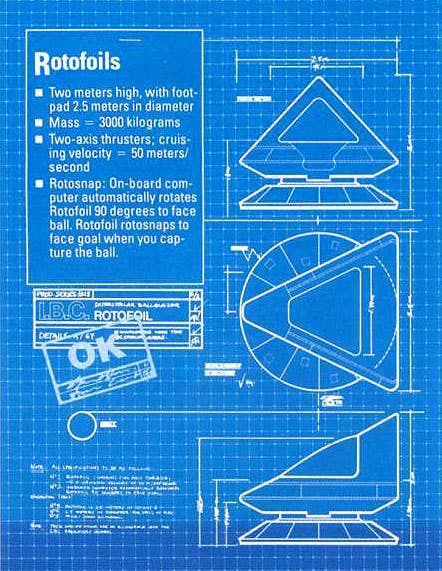

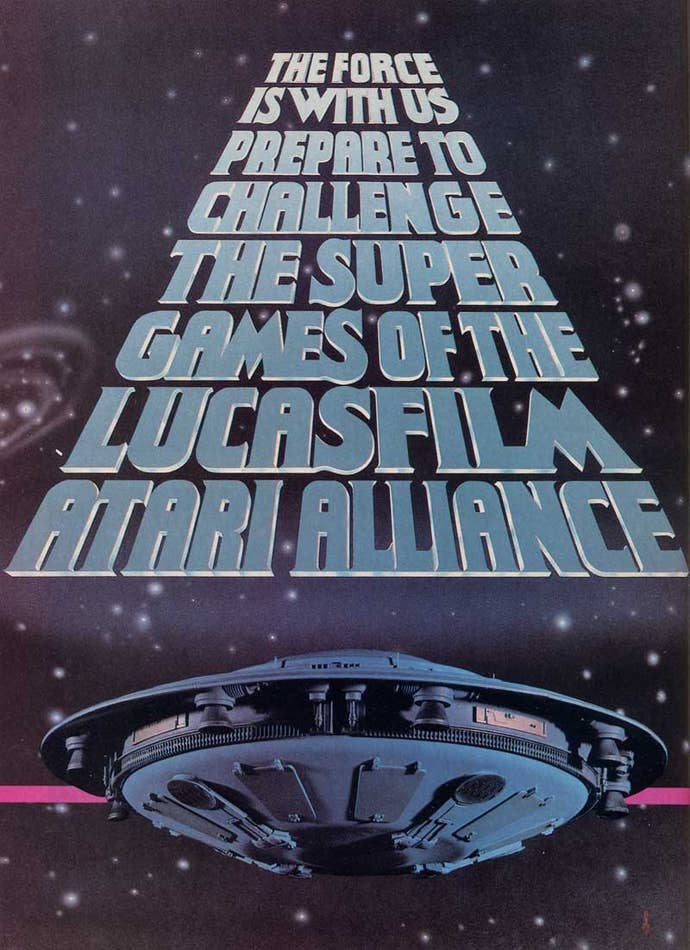

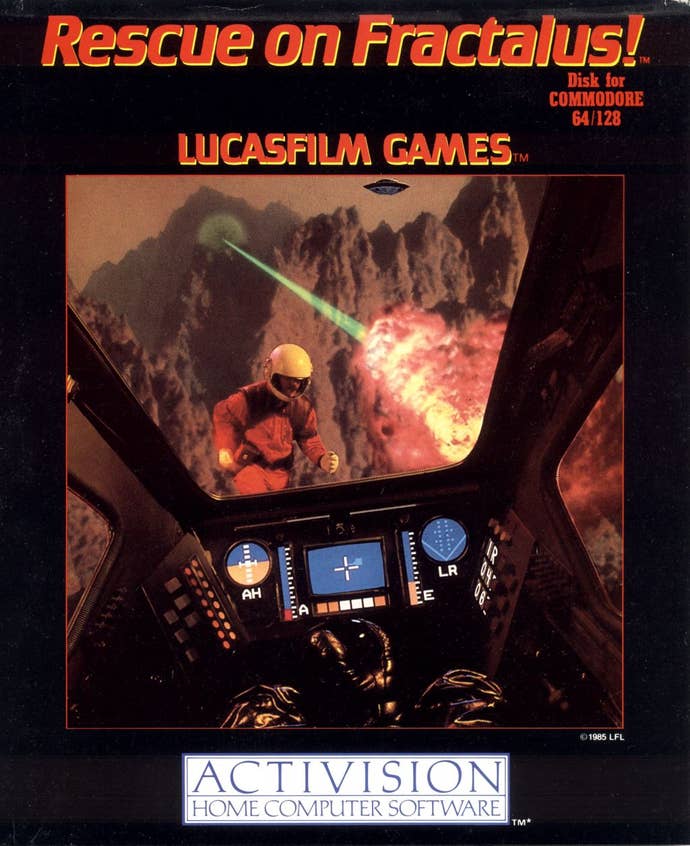

Activision, who'd just become the European distributors for Lucasfilm Games wanted to fly workmate Gary Penn and I out to the states to visit Skywalker Ranch and check out two upcoming games from the company. The prior year, George Lucas' nascent developer had produced two games – Ballblazer, and Rescue on Fractalus. Released on Atari 8-bit computers and the Commodore 64, both were critically acclaimed as innovative and imaginative. In a period when the majority of games were clones of coin-ops, Lucasfilm Games' releases were technically ambitious, and impressive in scope.

Having reviewed and highly rated both games, I was extremely excited to see what Lucasfilm Games was planning next. The trip was indeed a memorable one – my first ever to the US – and we were shown The Eidolon and Koronis Rift.

What struck me while talking to all of the Lucasfilm Games team members was the unusual vision that they all shared. Something important to remember is that this was 1985, a historically challenging time for the American video games industry. Three years earlier, the games industry had peaked, generating an colossal $3 billion in revenue. Two years later, it had cratered to an all-time low, garnering just $100 million in video game sales in 1985. There were few major players left in the gaming industry, most retailers had written off video games as a fad, and the only light at the end of the tunnel was an upstart console that had just hit the shelves from a company most people thought only made arcade games - Nintendo's Entertainment System. Home computers were also present in the market, but they were still very much a niche product compared to Europe, where they were booming.

Lucasfilm Games had been formed as the industry crested, and during the 24 months of the games business’ precipitous decline had produced just two games – an expensive proposition when many developers were creating multiple games a year. But then, those kinds of developers were usually producing games that were typical of the era: graphically simple arcade-style games designed around the limited life/coin-drop paradigm.

At Lucasfilm, there was a vision to push gaming way beyond the status quo. David Fox, project manager of Rescue on Fractalus, explained at the time, "I'd say that the people that came to Lucasfilm Games, or the reasons we ended up here, are because we're all very much impressed with the type of work that George Lucas did with his films, and we appreciate film type experience."

"So we designed Rescue on Fractalus and Ballblazer with a conscious effort to create that feeling and bring it over into the games. The games themselves – each of them came about in different ways. Like in the case of Rescue, it started out with me sharing an office with Loren Carpenter, and him being an expert with fractals. Well, we were wondering what would happen if we could somehow incorporate that on a small computer. And then the game scenario came out of that, and went in that direction. So in that case we came up with the graphics idea first – the game came out of the graphics routine. The other two games, Koronis and Eidolon, just went in the other direction the ideas were first and the graphics followed."

David added something else that, with the benefit of hindsight, seems particularly significant. "People seem to be looking for deeper and deeper games because they're not interested in video games any more. They want something that they can really spend lots of time in and explore the play areas of the game, so they need to be more and more complex, deeper and richer."

"l would say when we're designing a game, the aim is to create some sort of an experience. In most of our cases, it's trying to have something happen that we want to. We really want to get someone feeling like they're in a new universe, and to create an experience of exploring a new universe."

"It's the sort of thing that happens in a George Lucas film. It's like you've been transported to somewhere else. Most of us like that feeling and we want to be able to transport the person to another universe too, through a game that's really different. I think it's very exciting to do that. I wish we had wide screen and stereo sound and things like that, to make the experience even stronger. But we're doing the best that we can within the limitations of the machines."

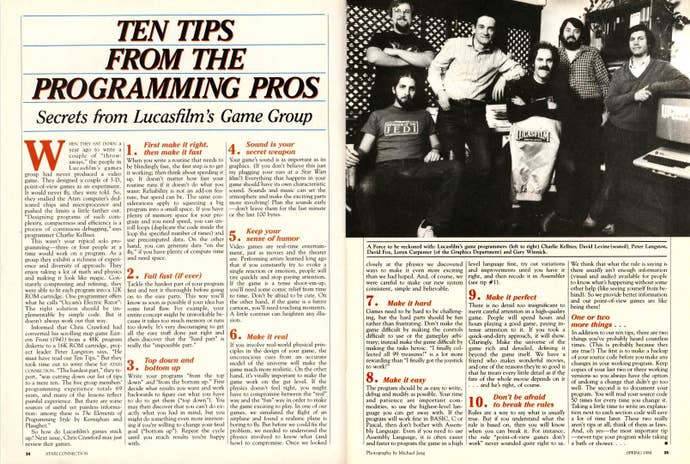

While this kind of rhetoric sounds like typical games design talk today, almost 30 years ago, this was seriously progressive stuff. I talked to many developers during this period, and their focus was almost always on making fun, entertaining and enjoyable games. Certainly absolutely nothing wrong with that. However, Lucasfilm Games was thinking with a mindset far closer to today's big-budget game designers than their video game making peers of yore. It was really quite inspiring, and gave an insight into what games would become in the decades to follow.

I left Skywalker Ranch feeling that Lucasfilm Games was one of the most forward-thinking and visionary developers of the period – a view I still hold today. I also left with several unanswered questions – I simply didn't have enough time to ask them all. However, little did I imagine that almost 30 years later, I'd finally get the chance to ask a few more. Which is what happened when Bob Mackey and I sat down with five of the original Lucasfilm Games team at this year's GDC in San Francisco. They'd all just given an incredibly interesting presentation that was part of GDC 2014's Classic Studio Postmortem series. Hosted by Noah Falstein, David Fox, Ron Gilbert, Steve Arnold, Peter Langston, and Chip Morningstar, we were given a fascinating insight into the early days of the studio.

One of the surprises for me was learning that George Lucas didn't decide to move into the gaming space because he was interested in games. Lucasfilm Games was actually set up so that the parent company could avoid the massive tax penalties it incurred due to the vast amount of revenue generated by the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises. By investing in his own company, Lucas could dodge those fees, so he created Lucasfilm Games and the Lucasfilm Computer division.

When I visited Skywalker Ranch in 1985, I'd asked whether George had been involved with the studio's games, and had been given a somewhat ambivalent response from David Fox. "In some ways – yes. It's his company and he's essentially the senior designer and developer of any project that happens here. He has been in from time to time to give us support on the projects we do."

Three decades later, the same question elicited chuckles and a far clearer answer. Turns out that Lucas' involvement with the games group was almost non-existent. Steve Arnold explained during the presentation, "The joke with George was that when we were presenting to him, he would look at something and consider it very deeply and say 'great!' and that was it. Getting a 'great' was a good outcome when you were presenting to George."

Bob wanted to know more about this, and asked, "I've heard George Lucas being described as a well-meaning figure who didn't really understand games that much. But he wanted to give his input on things. It seemed like he would show up, demand some changes, but not understand the amount of time and money that would go into it. Is the same George you guys worked with?"

"Not quite," says David. "The only suggestions I knew he ever made on any of the games were probably on Rescue on Fractalus, which was in the first couple of years of our existence. It was a year after we were there."

"He was a little involved in Labyrinth," says Steve. "Spielberg did the brainstorming on The Dig, the first generation. George was interested from a creative standpoint, but he's not a gamer. He's not a computer user. He uses a cell phone, but... This is how I would interpret it. He was looking for ways this new technology was going to expand the way that people engaged with stories. To the extent that we were doing that, that was interesting to him. We started doing things like the Indiana Jones games or the Labyrinth thing to try to experiment with that intersection of the story from the movie and the story from the game. So he was interested in that.

"But he's not a gamer. At a certain point it doesn't make sense to ask him for anything other than what he contributed to Rescue, which was the dramatic story element. It's not that he didn't care. He wanted us to be successful. He would say, I don't know your market, you guys should figure out what you're supposed to be doing."

Peter adds his perspective. "I think from the start, he needed us to prove that we understood the business, which is why he was as involved as he was at the beginning. He had seen what the computer division had done with the technology in the area that he knows about – film. And he said, this is great, I want to do this more elsewhere. Doing it in this area that he didn't know much about... He was proud of us, and respectful. I think maybe he even had the sense that he wouldn't want us come in and say, this movie should have this change, so he wasn't going to do that to us either."

"I think he also acknowledged the immaturity of the medium," says Chip. "One of the things he would say... he referred to us as the Lost Patrol."

"Affectionately!" say several of the team members almost simultaneously, eliciting smiles around the table.

"Yeah, affectionately," agrees Chip. "He once said in a company meeting, ‘they're out there somewhere in the desert, and occasionally someone will see their flag over the top of a sand dune, and we don't really know what they're doing, but someday they'll come back to us with tales of great stuff, heroic deeds that have been done. Until that day, we'll just have to hope for the Lost Patrol to return.’"

"I would guess that he was really interested in the educational stuff," says Peter.

Steve nods. "I've been working with him in that area for 30 years. We're still very involved together on the work that we started when I was working at the company. I know he's still engaged in that stuff."

A question I'd asked during my original 1985 visit was one that was probably asked by everyone who came through Lucasfilm Games' door – which was why wasn't the team working on any Star Wars games? At the time I was given a fairly curt explanation that the team was focusing on its own ideas.

During the presentation, David Fox shed more light on this. "We were told right up front that we were not allowed to do Star Wars titles. I was really upset – I had joined the company because I wanted to be in Star Wars."

Steve had added, "We were creating a culture that was designed around innovation... We had the brand of Star Wars, the credibility of Star Wars, and the franchise of Star Wars, but we didn't have to play in that universe. We were a group that lived inside a super-creative, technologically astute company and we got to do our own invention... We got to make up our own stories and call them Lucasfilm."

The story and invention aspect of the original Lucasfilm Games' titles was one of the questions I never got to ask in 1985, so I made it the first one I asked when we sat down together following the presentation. How did the team conceive those original game ideas? Were they born out of technological innovation, or were they stories that the designers wanted to tell?

David Fox jumps in immediately, "With Rescue on Fractalus, I wanted to be in a Star Wars movie. I wanted a game where it felt like I was flying an X-wing. That was why I came to the company, because I wanted to do that. It was really the idea of doing that, coupled with being an office-mate with Loren Carpenter, who was the de facto graphics whiz in the computer division."

”I asked him whether he thought it could be done. At first he didn't think it could be, but I guess he kept on thinking because eventually he said that he had an idea. In a few days – working on with a 6502 Atari 800 processor and assembler – he came back with a demo. I think it was literally a day or two after we gave him a machine to take home. So we knew it could be done, and that I could design the game around that. I think that's the only action game I did while I was there. Most of what I did was more in the graphic adventure genre. I got my experience. I got to do it. And that was it."

Peter switches the topic to Ballblazer. "For David Levine, it started out with a question about how could you do high quality graphics on a home computer? The coin of the realm was anti-aliasing. Everyone knew you couldn't do that on this little machine. So David came up with the idea of trying to make a checkerboard, and it worked."

"Then we started talking about what we could do with this checkerboard. The idea was, wouldn't it be great if there were some kind of sport on it? Then we had to think about how we could make it so you could see both players properly, and that led to the idea of what if we made it two screens? Then David did better and better at handling all the special cases in order to make the ground anti-aliased at all points, such that it really did have that look of sliding on ice. And so I think the idea of it being a sport kind of followed from this opportunistic path."

"Of course, both those games were just throwaway tests to see if our tools worked, to see if our assembler written in LISP was going to be sufficient. Actually, there were some other things proposed at the same time that did get thrown away, that were just little bits of experiments."

David suddenly pipes up, "Ewok Hunt!" Which elicits much laughter from the group.

"Well, sure," says Peter Langston. "There was Booger Hunt, too. And Leia Princess..."

"They always wanted to do Ewok Hunt" says Steve Arnold with a wry grin.

"I always remember, there used to be a thing on the whiteboard behind someone's desk, whenever we'd have journalists in to visit," reveals Chip Morningstar. "It said Ewok Hunt Design Meeting 3PM."

"Better than Ewok Hunt 3PM," quips Ron.

Laughing, Peter adds, "We pretty much did have an Ewok Hunt during the time when they were filming the Christmas special. They were filling the parking lot with Ewoks. You couldn't park anywhere"

Steve looks at Ron and asks, "The infamous Christmas special. Weren't you an extra in that?"

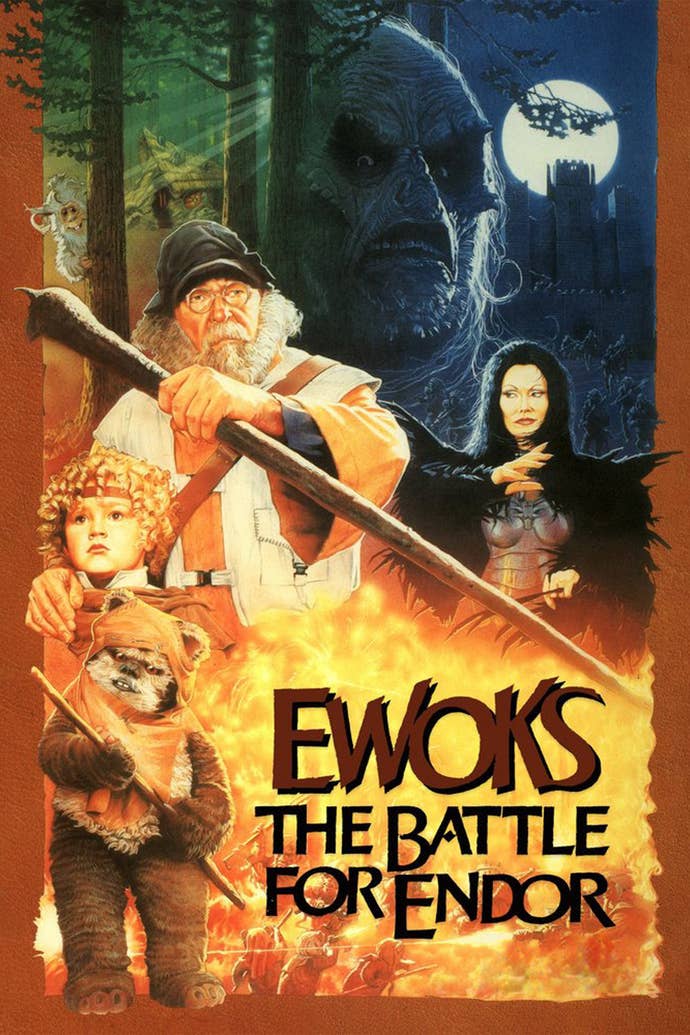

Ron ponders a moment. "It wasn't the Christmas special. What was it called, Escape from Endor? One of the Ewok movies. I was an extra. I actually was hunting Ewoks."

Steve asks, "That was when they were shooting you all running across the golden fields at Skywalker Ranch, right?"

Ron nods. "Yeah, it was this really hot summer, and we were up in these dry hills in Marin, dressed in these rubber costumes. It was just sweltering hot. The glamour of the movie industry!"

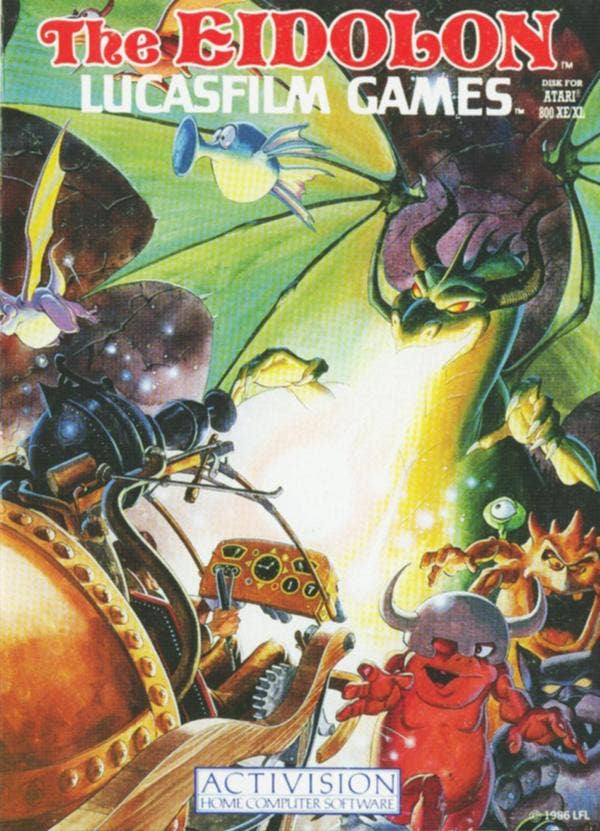

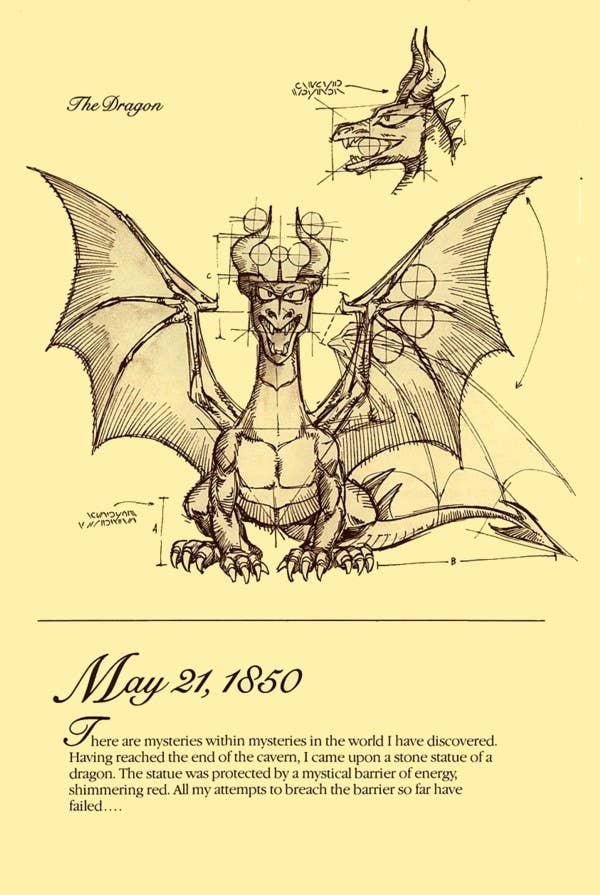

I move the subject onto The Eidolon, one of the games I'd seen being developed back in 1985. It used similar technology to Rescue on Fractalus, and I wanted to know whether the game was more of product of wanting to squeeze more out of the engine, or whether there was a creative vision that drove it.

David explains, "The Eidolon was Charlie Kellner's game. He was intimately involved in Rescue, also. Charlie just kept incrementally optimizing and refining that renderer, month after month. It kept finding its way into all kinds of different things."

Chip chips in, "Charlie just kept incrementally optimizing and refining that renderer, month after month. It kept finding its way into all kinds of different things."

David continues, "His idea was to flip it upside down and turn it into a cave. At the same time, Noah Falstein was doing Koronis Rift. He also based it on the same engine, but they added color shifts for things far out. It was like, okay, we know we have a way to render 3D landscapes, so what else do we want to do? Charlie wanted to do a fantasy game with dragons. We knew the technology worked, so it was more focused on being a game." "The cel-rendering engine, which was used to create the dragons and whatnot, ended up being the renderer for Habitat," says Chip. "That code kept getting recycled and repurposes and evolved into different directions."

Ron adds, "The animation system that started in The Eidolon was used all the way through Monkey Island, to some degree."

"Tools!" exclaims Peter.

"Yeah, we had great tools back then," agrees Ron.

"And collaboration", adds Steve. "Because you guys were always looking for something that somebody else had built that someone could adapt for another use."

Peter explains, "Research places like Bell Labs work really hard to make this kind of thing happen. They put people's offices in strange places so they all meet at the water cooler and that kind of thing. We just got together by nature. At lunch, discussing what was going on, you discovered things you could use in what you were doing, where you wouldn't know to ask that. That's another advantage of that small size."

Something I've always wondered with Lucasfilm Games' fractal graphic products is that they were very different from the voxel and more traditional polygonal graphics that are now very much the norm today. Why did computer graphics evolve in the way that they had, and why didn't fractal-generated graphics take off?

David answers, "Back then, the fractal technology was more about drawing dots. It was more about how to connect these points on the grid with a line that would stay consistent as you got bigger and give you more detail. Now it would be much more about little pieces of graphics. I don't know how you do it. It's not really my area."

Peter explains, "It was data amplification, the whole fractal thing. It allowed you to have a small amount of data from which you would generate a great amount of detail. And it's consistent."

David continues, "About four or five years ago, I got the team together and pitched LucasArts to do a sequel. Loren Carpenter whipped up a demo on the iPhone. You could fly around the landscape. I think we were really close to having a deal in place, and then the president of LucasArts, Darrel Rodriguez, was replaced."

Ron interjects, "He was the one that did all the Monkey Island remakes and stuff. He was a lot more interesting."

"Yeah, he loved the old stuff," agrees David. "He wanted to go back and pull that stuff out and engage the fans in a way that I thought was great. And then the company decided they wanted to do Star Wars again, to focus in that area, and all this stuff got pushed aside. I'd love to see it, but now I think it's even less likely – unless it was a different title."

Bob Mackey, a huge fan of the early LucasArts games, asks, "Right now I guess Disney owns everything you guys created at Lucasfilm Games. And there hasn't been any word about making these games available via services that distribute old games. How do you feel about that? Knowing that there are these amazing games you worked on that are all just unavailable unless you pirate them?"

David thinks for a moment. "Well, it seems like they're missing an opportunity. If they had a legal way for people to purchase them, I think people would do that, rather than trying to cobble them together with pirate downloads and emulators. But it's not Star Wars. I think they bought Lucasfilm for Star Wars, not old games."

Speaking of those old games, they're much loved and respected. I wonder how the team sees its legacy to gaming? How do they see themselves, and how would they like history to judge what they did?

There's a moment's pause as the team collectively thinks, then David breaks the silence. "The stuff I like the most is probably the graphic adventures. That's what I was associated with, so that's what I think of, mostly. But I don't know. There's still some stuff being done there, but... I think when you add the production value costs that you have to do now to make a game, that makes that kind of game much harder to do.

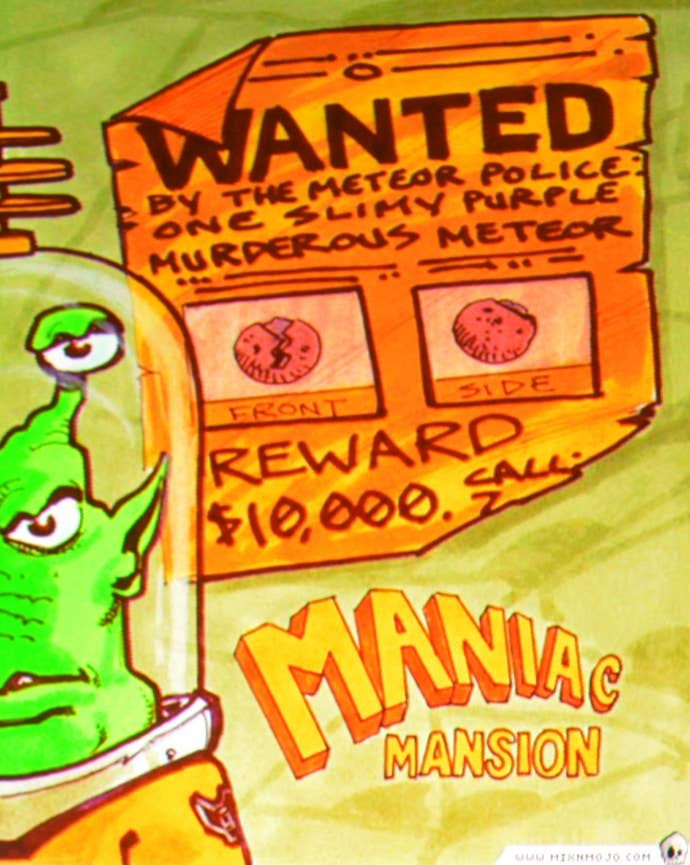

He continues, "In our presentation just now, someone asked a question about the challenges of doing humor in a game when you had a tiny amount of memory. Maniac Mansion was 310K. The entire game. Zak was on two sides of a disk, so it's probably in the same range - maybe 350k. I'm probably really good at Twitter, because we had to do text in 80 characters. Two lines of 40 characters each – that had to be funny. So everything was in shorthand. You couldn’t do much with the graphics, so it all had to be suggested.”

"You couldn't do much with the graphics, so it all had to be suggested. It was like doing a little puppet show. The little guy smiles, you turn this way and that way, and it worked. People maybe used their imaginations more to fill in the parts that were funny. Now you have to be explicit. If the timing is off just a little bit, it can fall flat a lot more. There are movies that are enormously funny that look great. It's just that we had so much less to work with that we had to focus on that part."

Chip points out, "If you have awesome technology, it's easy to fall back on it instead of designing a compelling experience. We even saw that in our day, where people who were pushing the state of the art, which we were, would often get that as pushback – well, it's all just technology. It's not an emotional connection."

Peter continues. "As you get more photorealistic, you also get more creepy, just because you can see that that mouth motion isn't right. The extreme might have been Grim Fandango, at the other end. It was so unrealistic that you immediately accepted it for what it was and it started to be very expressive. And not creepy, strangely enough. It's a cartoon. The people in Grand Theft Auto are really creepy, and not necessarily because they're doing anything creepy. They just don't quite move right. I think that's a hump. People will get past that hump, and then we won't have to deal with the creepy part, at least."

"Constraints and limitations are a really powerful creative motivator," says Ron. "Sometimes if you remove constraints and limitations, you end up wrecking what you're trying to create. Just because you have too much money or too much technology. I felt, with those early games, especially Maniac Mansion, we were so constrained that we had to make really smart choices on stuff. I think that's a benefit."

"The fact that we couldn't use Star Wars was a constraint," says Chip. "It generated a lot of creativity."

"I think of that as an anti-constraint," exclaims Peter.

"If we could have done Star Wars that's all we would have done," says Ron "That's all we would have made."

David adds, "The other constraint was that we had to do something that represented the company – something that, in the area of gaming, was as good as the Star Wars movies were in their area."

"We struggled with that," says Peter. "The graphics group was constantly on us for not being up to their par. Which, you know, they had these huge machines that could run all night to generate a frame."

"To me it was self-imposed pressure," says David. "Nobody ever said, your games have to be as good as the Star Wars movies."

"But there was constant teasing," says Peter.

David nods. "Well, the fact that the first few games were suggested to be throwaway games took all that pressure off. We could just experiment and not worry about how good they were. If they were good, maybe would do something with them. That really helped relieve some of that pressure."

Bob asks, "Lucasfilm Games started with a number of different types of games in different genres, but eventually became synonymous with graphic adventures. Was that the most natural fit for the group? Or was that a company directive – this is the best way to advance storytelling, the best way to advance narrative? Or was that just the most popular genre at the time for computers?"

David is the first to reply. "Two of us here represent the graphic adventure area, but there was all this simulation stuff that was happening – X-Wing, Battle of Britain, all the simulators, which were also really well-received. Maybe they're not remembered, because they weren't so impactful as the graphic adventures."

"A flight simulator is much more a creature of its technological era" says Chip. "You remember something that has a story and characters. You're going to remember those regardless of the medium."

David agrees. "You probably wouldn't go back and play an ancient simulator because the current ones are so much better, but the story that we had in those old games is still the same story."

Peter adds, "During the period I was familiar with – I dropped out after a certain period of time – the game choices and the emphases were entirely the personalities of the people involved. They were the things that turned their crank. There was no sense of, what does the industry need, or, what are people asking for?

Ron continues, "There was never a mandate from the company to do adventure games, or go, hey, the adventure game market is big, we should be in that market. We did adventure games because I was interested in it, David was interested in it, so we just pushed forward. A lot of things in those early days at Lucasfilm, there was no company mandate. It was whatever we were personally interested in."

The full Lucasfim Games Classic Studio Postmortem presentation from GDC 2014.

"The mandate, in some sense, was just to figure it out," says Chip. "I recall that within the group, there was this ongoing dialogue that permeated everything, about interactive experience. What is fun? What is a compelling emotional experience? What could we do that would make people want to play these games? There was a lot of going after the market, but not in an analytics, demographics, this segment kind of thing. But more in terms of, what kind of new experience can we come up with that would appeal to somebody other than the traditional core gamer? That was always more of an outreach thing, rather than just, how do we get our shares up?"

The day before this interview, I went back and re-read my old reviews of those early Lucasfilm Games titles just to refresh my memory. I tell this to the team, "What stood out when I was reading my review of Maniac Mansion was that the game was a new concept, and I had to explain how it worked to my readers. I ended up describing it in this really clunky way, because I had no vernacular to describe it. When I was reading that, I was just thinking, if I had difficulty describing it, how on earth did you think it up? What train of thought got you to that thing?"

"What kind of sick people are you?" says Peter with a laugh.

Ron explains, "A lot of the creative side of the game just came from Gary Winnick and me. We both really liked campy horror movies. We'd watch them and we'd talk about them. We just wanted to make a game that was this dumb campy horror movie about teenagers going into a house. That just came from our liking that kind of stuff."

"The whole interface for Maniac Mansion came from David. He experimented a little bit with that kind of stuff in Labyrinth, where you could choose things. I hated playing text adventures, where I had to type everything. I just hated that. So it was about coming up with an interface where I could point at the words. Again, it was reducing that verb set, picking from this small set of verbs and small set of nouns and simplifying that."

"You didn't have to guess what word they were looking for," says Chip.

"Yeah," says Ron. "You would just point at the thing or touch the thing."

"You knew what the universe of possibilities was," says Peter.

Chip continues, "The other thing that was really innovative in Maniac Mansion was the fact that you were controlling three different characters and switching back and forth, which was something I'd never seen before."

"That was an insane thing to try to do," says Ron.

"And it was great," says Chip.

Pete jokes, "It's something that Grand Theft Auto has only now discovered."

David explains, "The hard part wasn't so much the three people that you had, but the initial selection process, because that meant there were all these combinations of people that you could end up with, which hugely complicated the game. We had to make sure you couldn't get a combination of kids that couldn't win the game."

Ron nods. "That's a good example of one of those things where, halfway through the process, we were regretting that choice. We really didn't think it through. We did not think about how complicated it was, to have three characters out of a choice of seven, and all these different endings. But in some ways, we just plowed ahead. We didn't think about it. And what we got out of it at the end was something really cool, because we didn't really think about it. We just did it."

With the game being so complex, I wonder how they flow-charted the design.

Ron explains, "Gary and I created a little map of the mansion on this big sheet of cardboard. Then we had these sheets of acetate, that clear stuff. We had six or seven sheets, and we'd write all the objects – where it was picked up and where it was used – and then each of the characters were on a different sheet of acetate. We could layer these sheets down over the thing. But at the end of the day, it was completely flawed at some level. A lot of it was just... David and I were doing the script on it, realizing, okay, this choice is not going to work. And we'd try and come up with a last-minute solution to it. We tried to design it out, but so much of it was just figuring it out and then realizing it was all screwed up."

David takes up the story. "When I did Zak, I said, no way. Here is the four you get and that's it. It didn't have the combinations. I don't remember whether Zak was the first, or Maniac, but we used some project planning software – if this happens, then this happens. You could plot out the whole thing on a big printout, a fancy chart, so you could see where the chokepoints were in the game. Everything funnels through this point, or is there something that's missing? That helped afterward, to make sure there weren't any holes in the logic."

Ron turns to David and says, "I'm pretty sure you're the one who turned me on to that."

David nods as Ron continues, "I know I used that for Monkey Island. I completely had Monkey Island designed using these dependency charts, just because you knew everything. You could look at the charts and visually see how the flow of the puzzles worked."

"It's hard to keep it in your head, initially," says David.

It seems that that the Lucasfilm team had a lot of latitude to explore and be creative. I wondered whether they ever got into a situation where they worked themselves into a corner, or ran into a problem that they had difficulty in solving.

David explains, "There were lots of small things. Getting stuck and then walking over to Ron's office or Noah's office and saying, hey, here's this situation. We'd just do an impromptu brainstorm for about 10 minutes and come up with a solution. Okay, pick one of those and go off and do it. I remember lots of that. I don't remember just totally being blocked."

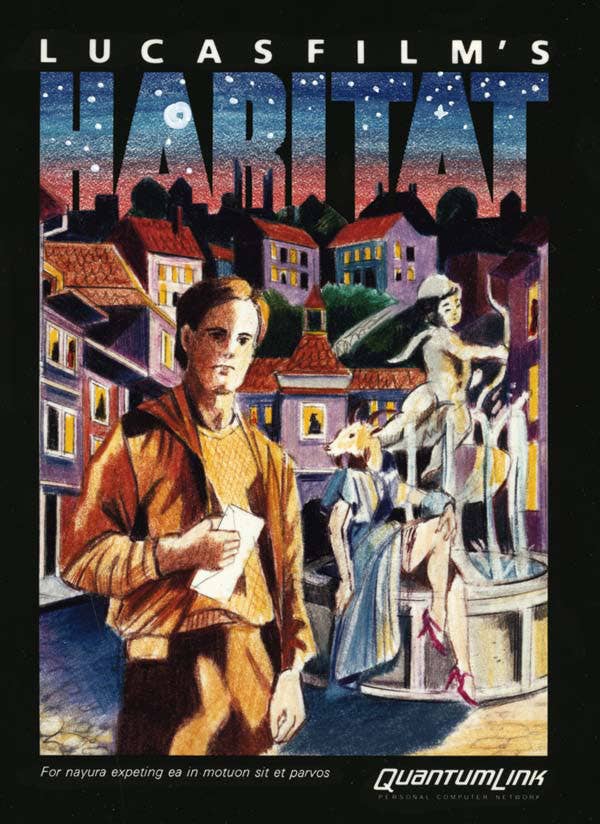

"Habitat was technologically the most ambitious thing we'd ever attempted," says Chip. "There were times where it just wasn't working and we didn't know why. Everyone was tearing their hair out. There was this moment of despair – are we going to solve this problem? But you always solved the problem. It will eventually yield to a sufficient amount of people standing around worrying at it. But you do have that moment of... is this going to be the fatal flaw? But we never actually had the fatal flaw. We had projects that just got a certain distance and we said, no, that's not going to work, and put them aside. But that's a different sort of thing."

I ask whether this process bought the team closer together.

"It's the only way to work," says Chip. "It's no fun otherwise."

"I think that there is a culture that Peter brought that stuck with the company for a long time," says David. "Either you brought it, or it was part of the division already. But the idea of a lot of peer review stuff. I remember you said, here are some resumes. We're all going to interview these people. What do you think? We all had to vote. That was there for the whole time I was there – maybe not across the entire division, but for sure within your discipline. If you were a programmer other programmers would interview you. If you were a designer all the others would do it."

"There was definitely a selection for interpersonal chemistry when we were hired," says Chip.

Peter reveals, "I wanted to do the peer thing because that had worked so much better for me in life, rather than having a hierarchy. I really didn't know what the rest of the computer division did, because basically, when I arrived, I was hiring. I didn't have a chance to get what their culture was. It seemed like a friendly culture."

David takes up the story, "There was a point where the flat hierarchy become a problem. That was the late 80s. After we did the Indiana Jones game, Steve asked me to be the director of operations for a year, and I would try to bring in some people to manage the art group, customer support, QA. They'd talk to me and then I'd report to him. I agreed to do it, if I could do it for only a year, because it didn't sound like a lot of fun. That's when we grew from 10 or 15 up to like 60 or 80 people."

Peter interjects. "Psychologists say that it's at seven that you need to go to a layered approach. We did very well to get to that many..."

David nods. "We probably waited longer than we should have. But even when we did that, within those groups, they still had a flat structure."

As the company grew, I wondered whether there was any kind of competitiveness between the teams.

"We liked to impress each other," says Peter.

"Chip adds, "It was always nice to show off, but it was like, hey, I did this cool thing, and everybody was like, hey, cool. We were sharing."

"The positive thing was, you do a cool thing and people think it's really cool," says Chip.

Ron jumps in, "It was also – this thing is really cool, now how can I use that? Because there were a bunch of things in Maniac Mansion that Chip wrote – animation systems and memory management systems – and in Eidolon. It was always looking at cool stuff that people were doing and saying, how can I use that in my game? How can I use that little piece of tech?"

"That's cool. Gimme!" grins Peter.

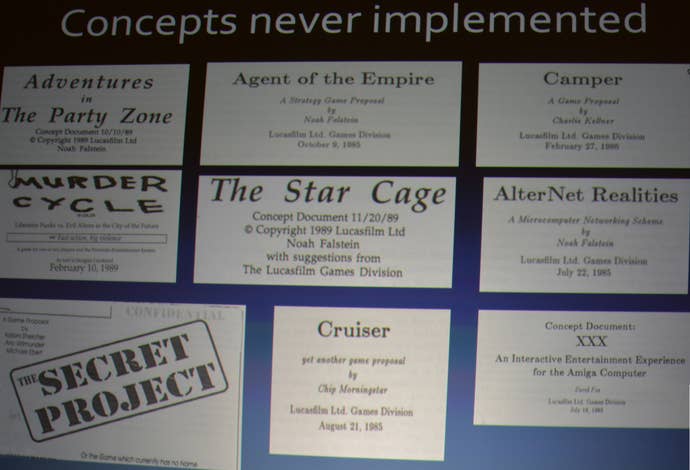

Bob asks about a slide that was featured during the Lucasfilm Games postmortem that showed several unused concepts for games. Were there a lot of those at the time?

The team all agrees. Ron says, "One of the things I really liked was, we'd often write these little one-page design documents and we'd just pass them around. If people were excited about them, maybe we'd do a little more of the design. If enough people were excited about it, maybe it would become a project. Maniac Mansion started out that way."

Chip continues, "One of the things that happened is that somebody would just have an idea. They'd write it up, like Ron said, and circulate it around. It would get a certain amount of feedback and fleshing-out and turn into one or two or three pages. Steve kept a file of these. He had a file cabinet in his office, literally a file drawer, with all of these different crazy ideas. He had that as an inventory. When people would come sniffing around, potential business partners, he'd have an inventory of stuff to try to pitch at them. That's how a lot of the projects we did ended up getting greenlit. We just had a backlog of ideas."

"That's what happened with Quantum Link. I think there's some Amiga stuff that happened that way. They were looking at it. There was a project with RCA. There was a project with Intel. There was a project with National Geographic..."

"Part of that was, the company was very stingy. It really was. It has this image of being palatial, but the company was very tight-fisted. Part of our mandate was not to be a cost center. If we wanted to do anything, we had to find somebody to foot the bill, because the company wasn't going to invest in it. We got very good, very creative. We did a thing with Apple. We had all of these projects. And we could get away with that business model because we were Lucasfilm. We were this brand."

Peter agrees. "We got our original million dollars basically because we were Lucasfilm, and somebody wanted to pay us money to let them be associated with us."

David ponders. "I'm guessing that changed at the point where we became our own publisher. I'm sure that no one funded Maniac Mansion because... That was the first Lucasfilm game?"

"It was, but it was originally being published by Activision," says Ron. "It was published abroad by Activision, but in the US, something happened and that deal fell apart, and Maniac Mansion became the first self-published game."

David says, "For the ones after that, we did fund them ourselves."

David says, "I don’t remember a lot about, ‘Here's your budget.' Do you remember any of that? When I had to start doing budget stuff for other things, I was like, I have to budget this? Because basically you say, here's the game. It'll probably take me about this long. I'll need this number of people. And they'd say, okay. I'm sure Steve did a budget then."

"Yeah, Steve was very good at hiding all of that nasty stuff from us," says Chip. "One of the things is, and I only found out about this years later... In the period that we were doing Habitat, the company was actually in very dire financial circumstances. We came very close to having the whole thing shut down. And he hid the whole thing from us. We were all thinking, hey, this rich, wealthy, fabulous, successful movie company, but of course the movie business is a feast or famine kind of business. There were a few famine periods in there. And the Lucasfilm enterprise is incredibly money-sucking, because it has all these very expensive capital-intensive facilities it has to maintain."

"Not to mention Howard the Duck," says Peter with a laugh.

"I understand we made a profit off of Howard the Duck," says Chip. "The studio just put up a big pile of money to pay for it. George just lent his name to get the money."

These days, to keep the money rolling in, companies tend to create franchises with many sequels. Outside of the Monkey Island trilogy, there weren't that many sequels. Bob asks whether the team just wasn't interested in sequels? Or was it more interesting to approach new ideas?

"Day of the Tentacle was also a sequel to Maniac Mansion. But... I would have loved to have done a Zak sequel, but I left before I could do that," says David. "After I did that year as the director of operations, I spent two years inside the company, inside Lucasfilm, but in a small group called Rebel Arts and Technology, where we were doing location-based entertainment projects. That was a partnership with Hughes Simulations. After that closed down, I couldn't imagine going back to doing home games, so I left. But if that hadn't happened, and I had stayed, I probably would have done another Zak."

"The concept of doing sequels was a creative decision, says Ron. "It wasn't a business decision. Nobody said, hey, Monkey Island did really well – it actually didn't – so let's make Monkey Island 2. That was more of a creative thing in me. I wanted to make a sequel to that stuff. So I think they were more creative decisions than business decisions. Now it's all about making sequels because you have this product franchise."

Peter says, "Inherently, some ideas make sense to sequelize, because you haven't used up the idea. In others, you have used up the idea, but it did really well, and so the decision to sequelize it is based entirely on the market, and it's a strain. Probably Lucasfilm would not have done the strained ones if they could possibly avoid it."

One of the more innovative ideas to come out of Lucasfilm Games was Habitat, the very first online persistent world. It essentially set the groundwork for the MMOs that would eventually follow a decade later. I was curious to know if Habitat had continued to evolve, where would the team have taken it?

Chip explains, "We actually had some opportunities to take it various places later. Lucasfilm licensed it to Fujitsu for the Japanese market, and later on they brought it back to the U.S. under the name WorldsAway. We were able to do another kind of generation of the same thing with better technology. Randy Farmer and Doug Crockford and I actually started a company in the 90s called Electric Communities that was intending to do the next-generation idea, which was to talk about things like making the world more open-ended, making it extensible, and making it decentralized, so people could add new things to the world and have the world be this ongoing, unfolding experience."

"That turned out to be technologically more ambitious than something you could get away with in a startup, although we did invent a lot of cool technology. The closest thing to that now that you see is probably Second Life, which is interesting, because Second Life, while it has some very interesting qualities, is kind of a sterile environment. When you have an open system, where people can add content, there's a producer and consumer economy that you need to have. You end up with these things that are pure producer environments – there's a reason to create stuff, but no reason to consume it. And so being able to create an open-ended world, yet one in which you still have a reason to be there, some purpose for the people to interact with it... Games like World of Warcraft give you a reason to be there, but it's kind of static. I would like to see if you could match those things up and have something that's both dynamic and extensible and creative, and yet at the same time gives people a sense of purpose."

"One of the drivers with Habitat was, I don't know how to do AI, so we're not even going to try. We're just going to say, here's an interesting environment, and the entities you interact with are actually people. They have fully intentional human beings behind those characters, and therefore they exhibit the richness and subtlety and idiosyncrasy that real people have. They don't reflect a single creative vision, a single creative mind, or even a small team. It's a whole ecosystem. I think that potential has not been explored."

And with that, our time with the team is up. Of course, I still have yet more unanswered questions. Hopefully it won't be another 30 years before I get to ask them.