How Ultima 4 and Wasteland Ushered in a New Era of Maturity for RPGs

HISTORY OF RPGS | Inside Ultima 4 and Wasteland, two critical attempts to bring meaning to the genre of RPGs.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This is the sixth entry in an ongoing series by Retronauts co-host Jeremy Parish exploring the evolution of the role-playing genre, featuring insights from the people who created the games that defined the medium.

A decade after the earliest computer role-playing games made their debut on PLATO terminals at American universities, Japanese designers defined their own distinct approach to the genre by paring it down to its essence. Dragon Quest and the hundreds of games it inspired gave players a very small amount of freedom within narrow parameters. This marked a significant change from open-ended American RPGs, but it proved to be a perfect fit for the tastes of Japan's gamers.

Back in the U.S., however, computer RPG designers chafed at the limitations that defined their digital adventures. Most of these creators had cut their respective role-playing teeth on tabletop games, where play mechanics existed primarily as rules of order for stories that were bound in scope and direction only by the game master's imagination... or their willingness to entertain players’ unpredictable whims, anyway. Computers, especially the primitive home computers of the early ’80s, could only hint at the expansive chaos of a great tabletop session. With the likes of Wizardry, The Bard's Tale, and Ultima having laid down the preliminary outlines of PC role-playing, developers now set about the task of pushing the boundaries beyond those cramped basics.

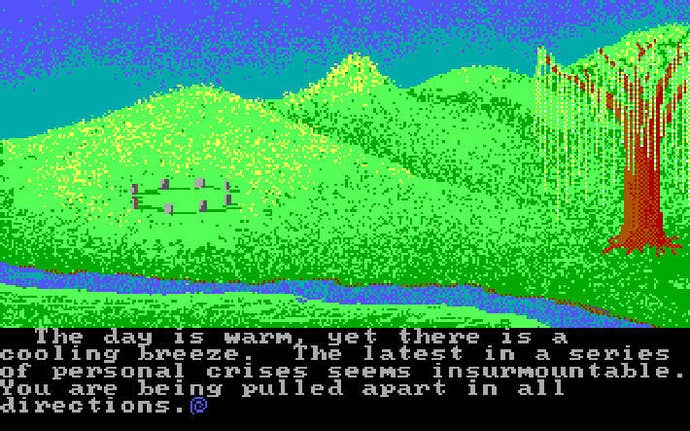

Fittingly, the first meaningful attempt to bring greater depth to PC RPGs came from Ultima’s creator, Richard Garriott, by way of 1985's Ultima 4. Throughout the initial Ultima trilogy, Garriott experimented with a variety of narrative and mechanical concepts before settling down into a comfortable groove with Ultima 3: Exodus. Not only did Exodus lay down the foundation for the workings of future Ultima games, it also brought the series' story cycle to a self-contained stopping point. With his game design formula locked down, and freed of the need to continue some overarching narrative, Garriott took the opportunity to reconsider the very concept of the Ultima franchise. What could the series become? Was there room for more than combat and looting?

"My earliest games really were just about fighting monsters and collecting treasure," says Garriott. "There was a story, but it was pretty much go 'save the princess' or 'kill the big, evil wizard.' Ultima 3 was the first game I published myself through my own company, Origin, so it was the first time I started to get letters from people who had played the game. For the first time, I actually could see what was happening in the heads of people playing my games. I was shocked to see what those letters contained."

Garriott learned his fans hadn't found the meager amount of text contained in the early chapters of Ultima to be a disappointment. Instead, like an impressionist painting, the games’ terse dialogue boxes provided just enough information to help fire their imaginations. Fans happily filled in the details themselves, becoming their own de facto game masters. "I began to see people reading story meaning, even though there was no real story in those games," he says. "People began to read between the lines and think I was trying to tell them something meaningful, when I wasn't."

Equally enlightening were the anecdotes players shared about their behavior. "Some people liked to replay the game to be quite sinister," he recalls. "They'd go kill off all the villagers. They'd steal from every shop. They liked to kill my character, Lord British. I realized these people were playing to min-max their way to the top, not to play any story they perceived." To Garriott, these patterns of behaviors spoke to failings not of Ultima fans but rather shortcomings in his own game design and the conventions of the genre at large—flaws, he realized, that were incumbent upon him to correct.

"The bad guy was just sort of waiting there for them, not doing anything bad to be worthy of your wrath. You were the plague of locusts killing and sweeping up everything in order to become powerful and rich. I thought, 'There's something wrong with that.' I was expecting people to be heroic. But I'm the one who put in the feature that you could steal from the shops, right? They couldn't have killed the NPCs if I didn't allow it.

"So, I said, 'OK. I'm going to switch it up.' I started writing Ultima 4: Quest of the Avatar. I deliberately said, 'I'm going to let people play the way they've been playing, but if you go through the town and kill everybody or you steal from that shop, that person's not going to want to help you in the future.' If you need [a key item] but you've been stealing from that shop, they'll go, 'I'd love to help the hero, but you are the most dishonest thieving scumbag I've ever met, so I'm not going to help you.'"

This represented a bold and unconventional change in the underlying fabric of role-playing games, and Garriott's friends and business partners worried that upending the genre would lead to Ultima's ruin. "Everyone told me, 'People aren't going to like it,'" he recalls. "And I said, 'You know, I still think it's the right thing to do. I think it'll actually make a better game.'

"I wasn't trying to take a moral stance—I literally thought it would make a better story experience if I did it this way. So despite the objections, we produced this game about ethical parables, and it was the first number-one best-selling game I released."

Shipping in September of 1985, Ultima 4 arrived at a critical point in time. The American video game market had begun to rebound from Atari's collapse several years prior; Nintendo would launch its wildly successful NES home console in the U.S. the following month, the vanguard of a revitalized industry. At the same time, however, parent groups around the U.S. had begun to fret about satanic imagery and themes in children's entertainment ranging from music to tabletop games. That trend didn't go unnoticed by Garriott, and Ultima 4 turned out to be effective counter-programming to the moral panic of the era: A computer role-playing game whose entire theme emphasized positive ethical choices.

"No question, that was an influence," Garriott agrees. "A lot of the people leveling that criticism were these often TV evangelists who were pillaging money from their followers while committing adultery. I would actually often pull those people, if not literally by name but by reputation, in as characters and vignettes within the scenarios that I'd build out. I said, 'OK, now let me show you how a lot of people who claim to be good really aren't, and a lot of people who appear to be rogue-ish are just surviving. Once you get them out of their need to survive, they're actually far more honorable than these peddlers of hypothetical sanctity.'"

Ultima 4 took a different approach to role-playing than anything that had come before it. While the game retained the look and mechanics of its predecessors and even scaled up its world to a size that eclipsed all three earlier Ultimas combined, killing wasn't the point. Players didn't set out to slaughter monsters or defeat some nebulous villain in a palace at the edge of the world. Rather, they sought to become the Avatar, the human embodiment of virtue. To achieve this, the hero's party doesn't set out to defeat bosses or loot treasure. Instead, they seek out tokens of enlightenment while upholding the tenets of the world’s Eight Virtues: Honesty, Compassion, Valor, Justice, Honor, Sacrifice, Spirituality, and Humility.

The abstract nature of this quest forced Garriott to rethink the player's relationship to the world. "We were very tightly focused on ethical behavior," he says. "I tried to fill the games with as many ethical parable tests as I could. When you do that, and especially when you don't tell somebody immediately whether they've passed or failed the test, it means they don't really know. If something looks like a test and it might be a test, they still act like it's a test."

Trials in video RPGs had typically amounted to major battles against hideous monsters and powerful warriors. The tests in Ultima 4, on the other hand, came down to the player's moment-to-moment choices throughout the quest. Did they give money to beggars, or did they steal from shopkeepers? Even the hero's behavior in mundane combat encounters factored into their pursuit of the Virtues.

"We'd do things like saying creatures like wolves and bears are not evil," say Garriott. "Now, hunting them for food, in a medieval setting, is acceptable. But killing them wantonly is wasteful, at the very least. So, if a wolf was attacking and you ran away from it or injured it to where it ran away from you, you got a little virtue point. On the other hand, if there was something that was evil, you'd get a bonus for defeating them. Conversely, if you ran away from something evil when that creature was weak but you were powerful, meaning you could have vanquished it but you fled in fear and didn't save whoever else might be targeted by that creature in the future, then you would take a hit."

Though Ultima 4 still didn't come close to offering the narrative flexibility of a tabletop role-playing session, it represented a critical step within video games to push the genre back toward its origins. Garriott's gamble paid off not only in terms of sales, but also in critical acclaim. More than three decades later, Ultima 4 continues to be regarded as one of the greatest and most innovative RPGs of all time, paving the way for works as varied as Mass Effect and Undertale.

It also helped prompt the creations of an equally significant take on the RPG from Interplay, the studio that had made its mark on the genre with The Bard's Tale. The Bard's Tale won over PC gaming fans upon its initial debut and continued to impress through two sequels. But at the same time, Brian Fargo (a longtime friend of The Bard's Tale designer Michael Cranford, whose role in the trilogy expanded over time to that of producer for the third chapter) found himself frustrated by the same narrative disconnect between tabletop and video RPGs that had nagged at Garriott. Fargo began planning his own take on the RPG, one rooted firmly in the open-ended storytelling traditions of pen-and-paper role-playing: Wasteland.

"With The Bard's Tale, we tried to make it such that the freeform game really came in terms of the party make-up," says Fargo. "We gave players different ways of surviving through the dungeons. We would find that your party, for example, looked wholly different than mine, or you were able to find an exploit because of your cleverness. You had that sense of playing the game your way."

"It wasn't until later on, in the case of Wasteland, where we started trying to open it up from a story perspective and letting people play it in different ways."

Again, both Garriott and Wizardry co-creator Robert Woodhead had found that players were happy to fill in the empty spaces of computer RPG stories on their own. The RPG, after all, was fundamentally a format powered by imagination. With tabletop role-playing sessions, players envisioned monsters and dungeons based on the raw story provided by game masters; computer RPGs simply flipped that relationship. They offered vivid visuals but required players to come up with their own stories and personalities for teams of characters who, functionally speaking, amounted to little more than their combat capabilities.

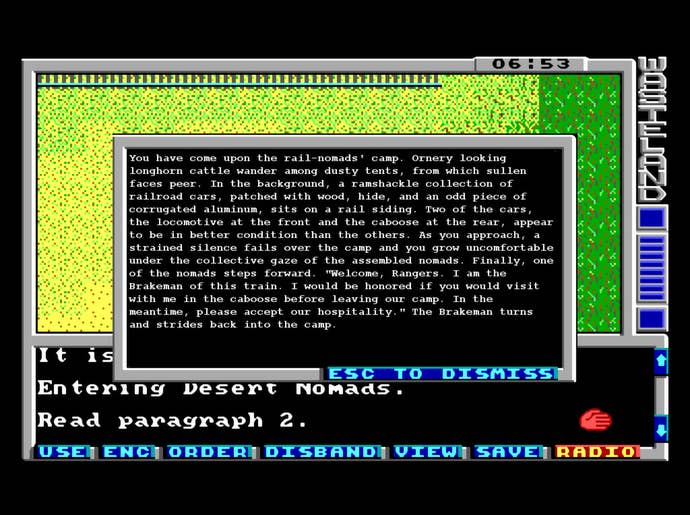

With Wasteland, Fargo aspired to ease that burden for players. This new RPG would feature an unprecedented amount of in-game text, enough to give players considerable freedom of choice. Wasteland's story would adapt to reflect the actions of players, reflecting the decisions they made throughout their journey.

"I'm sure somebody could name another," says Fargo, "but I feel like [Wasteland was] one of the first RPGs to have an open-world mood to it. You could go anywhere you wanted. You could try to take on areas that were not fit for your level yet, and if you got killed, that's OK. The ability to play a story your way, to me, was a radical shift."

Like his fellow computer RPG pioneers, Fargo cut his teeth on Dungeons & Dragons. His love for the genre, he says, "goes all the way back to my high school days—definitely First Edition. I still have my original monster manual and the dungeon master shield." Fargo credits the screen behind which game masters conducted their sessions as a valuable psychological tool that helped inspire his approach to game design. "You could roll the dice and not let them see what you were doing, or sometimes you'd roll the dice but nothing was happening, just to mess with their head. The thing that drew me to it was the social aspect. We tended to play more of a freeform game."

However, unlike Bard's Tale creator Michael Cranford, Fargo appreciated the precision of RPG rule books, seeing them as an essential part of the tabletop experience. "There were rules, which I loved—you were almost part-lawyer. It was like, 'I have my cone of silence.' 'Well, no. You're outside the 30-foot range.' We had all these sort of technicalities with the rules, trying to trip each other up, which was always kind of fun.

"But then there was the freeform side of it where the dungeon master would take latitude in telling the story or improvise, based upon us coming up with clever solutions. I really liked the storytelling aspect of it. You have your character, and you're living in that world, and there was a great risk factor to all the hours you put into the character."

More than any computer RPG before it, Wasteland embraced both the rules of the genre while trying to extrapolate them into interesting, dynamic story events. Fargo had plenty of experience designing and programming games by that point, but he realized early on that his vision for Wasteland was far too ambitious for a single person to handle.

"That first game took us four years to make," he says. "Wasteland took a long time, and the way it was done was very technically challenging. Each square you stepped on basically would execute a small program. Did they use the rope here? Did they talk there? Have they been here before with this thing? Going square-by-square and looking at it and what kind of dice roll would be put up against it was extremely time-consuming. But it was the cascade of effects of things that you did that made it so interesting."

In Fargo's estimation, Wasteland's complexity marked a turning point. "We were moving away from one-person [projects]. The Bard's Tale was more or less one person, as was Dr. J Vs. Larry Bird, and Archon, and M.U.L.E. We were starting to move away from that, and Wasteland was, for me, the complete pivot of bringing in an entire team of people and attacking this in a different way."

This was, in effect, a natural extension of the approach that had emerged over the course of The Bard's Tale trilogy. "The Bard's Tale III had been a bigger effort in terms of number of people that were required already," Fargo says. "My role started shifting. I became a producer." As such, he says, one of his key tasks was to ask, "'What are the sensibilities we want to hit?' I would bring in like, Michael Stackpole, to talk about the touch points that we want to hit. We brought in a lot of different writers [for Wasteland], so you had Mike, Liz [Danforth], and the others, each bringing a very unique style to their areas. You got a different diversity than you would have with a single writer.

"I don't know anybody else that was doing that in the same scope that we were. I wouldn't pretend to know everything behind the scenes of what was going on, but I brought in a bunch of professional writers. It tended to be in those early days that we [programmers] would just write our own stuff. If there was dialogue, we would just do our best. But it turns out writers are best when they're writing, and musicians are best doing music. So different voices and real writers were able to help punch it up. Back then, everything was text, so what you read had to be interesting, and they really excelled at that."

Ultimately, Interplay's ambitions for Wasteland proved to be somewhat more than the tech of the era could support. The entire game had to fit onto diskettes, which for most users in 1987 meant single-sided disks with a capacity of 360KB. Wasteland's extensive branching text trees alone could easily have filled that space without even accounting for engine code and graphics. So, Interplay cheated by shipping the game with a massive companion book that contained extensive information on the world along with story vignettes—making it a sort of auxiliary text storage device that also handily worked to discourage piracy.

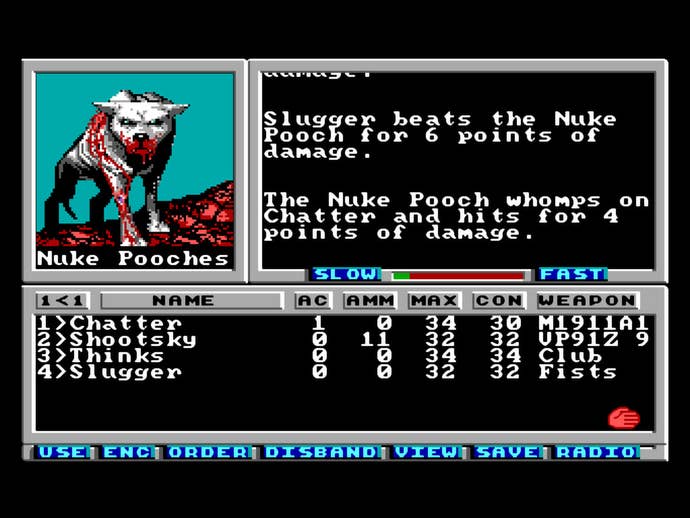

Another area in which Wasteland differed significantly from previous RPGs was in its theme. As the title suggests, the adventure was set not in a medieval kingdom or fantasy dungeon but rather in a near-future version of the United States, one reduced to ruin by nuclear warfare. Although Cold War fears of "the big one" had finally begun to fade by the time Wasteland arrived in 1987 thanks to the normalization of American and Soviet relations, Interplay's pioneering RPG presented no less compelling a setting for a role-playing journey. After all, it had already proven its merit through the films and books Fargo loved.

"I was quite obsessed with The Road Warrior at that point—I must have seen that movie 10 times," Fargo admits. "It was my absolute number-one favorite movie for years on end. I always was attracted to that subject matter. I used to love Planet of the Apes, which was dystopian in a way. There was the Omega Man, and a lot of my Heavy Metal comics were focused on that. Even when I watched The Twilight Zone, there'd be like one guy left on the planet. There was something about that that I was drawn towards—this dystopian future where the cards all get thrown up in the air and everything restarts."

There was more driving the choice to set Wasteland in a post-apocalyptic nightmare than its designer's love of Mad Max. Fargo saw the near-future survival theme as a way to ground the story and make it more approachable for audiences who didn't necessarily obsess over Lord of the Rings or Star Trek.

"We wanted to simulate real-life concepts," he says. "That's how we ended up using the mercenary spies and private eye system. The thing with fantasy is, if you see a glowing sword and had played Dungeons & Dragons, you know what a +2 sword's going to do. But if you don't, you're not going to have the context for it. But if I play something where I see a grenade or an Uzi, I know exactly what to expect.

"We also wanted to do more modern things like picking locks and climbing walls and sneaking—things people could relate to, that would put them into a world that felt like something they could identify with. You don't really get how to go from here to Buck Rogers, but drop nuclear bombs all over the planet, and it's going to revert you back to the old age of the brutish surviving. We can all identify with that as a possibility."

Wasteland therefore dropped players into a desert marauded by bandits and gangs, a place where mere existence took on a hardscrabble edge. The game's presentation resembled a hybrid of Ultima's top-down perspective and Wizardry's windowed combat, but neither the locales nor their inhabitants resembled anything from those other RPGs. Players could sneak into military compounds, roll the dice in what remained of Las Vegas, or fight punks over the rights to make jukebox selections in a dive bar.

In some senses, Wasteland feels like a reaction to Ultima 4. Rather than coax players onto a predetermined ethical pathway, Interplay's writers left the numerous possible outcomes of its scenarios open to interpretation. "We don't like to put morality on it," Fargo says. "We prefer to have a cause and effect that makes sense. We don't want want you to play the game and say, 'OK, I've killed all those people, so now I can't win the game. [We prefer to] make you live with the effects, but we don't want to make the game unwinnable because of what you chose to do."

As with Ultima 4, the decision to field questions of ethics and morality made Wasteland a richer, more satisfying game experience. However, the two games differed wildly in both tone and style, which spoke to the burgeoning maturation of the genre. Both raised questions about the nature of right and wrong, but only Garriott's story provided definitions. Wasteland left things more ambiguous, forcing players to once again use their imaginations to fill in the details.

"Sometimes when people talk about morality, it tends to be more black or white," says Fargo. "You’re either the good guy or the bad guy. But we tried to put you in situations where there was no clear decision about whether you were a good or bad guy, or else we created unintended consequences.

"We also tried to create content that you wouldn't see if you chose a certain path. It was a combination of a lot of little things that gave it a different vibe. If something felt immature, or sophomoric, or stupid, I avoided that, but I always encouraged the writers to put players into situations where they'd really be torn. That's the beauty of RPGs—you can actually feel bad about what you're doing. We show you this great reward you could get at, this fantastic weapon that's going to make your life so much easier. But you have to do something really shitty to get it.

"Watching people agonize over that decision is beautiful, and that's what makes a role-playing game great. 'I really want it, but I don't want to have to kill these innocent people.' Well, they're not real people. But in your mind, they are at that time. If we've done a good job, you're always worried about the repercussions of what you've done."

Although Wasteland amounted to a modest commercial success compared to mega-hits like The Bard's Tale and Ultima 4, it's nevertheless proven highly influential. A decade later, Interplay would produce Fallout—essentially Wasteland 2 in all but name (said name was bogged down in rights issues). Fargo, who now runs recent Microsoft acquisition InXile Entertainment, successfully crowdfunded a proper Wasteland sequel several years ago and currently is well into development on a third entry in the series. Beyond Fargo's own work, Wasteland's trademark branching, moral-based story design has been echoed in series like Baldur's Gate, Shin Megami Tensei, Tactics Ogre, and more.

It's entirely possible the narrative design Wasteland pioneered three decades ago will never truly be superseded, at least not in single-player RPGs. Where dungeon and inventory content can be automatically generated easily enough, effective storytelling requires a human touch. (One need look no further than the lackluster and repetitive nature of the procedural quests in Bethesda's Skyrim to see this fact in action.) As in tabletop gaming, the dynamics of social interaction in computer RPGs are most effectively provided by other people. Still, Wasteland and Ultima 4 both demonstrated that RPGs could be about something more than laying waste to ogres and goblins—or that, at the very least, they could bring some actual meaning to those acts of violence.