How Two Developers Used Games to Wrestle With the Dark History of Taiwan and Iran

Two nations and the two games that tell the stories of their troubled past.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

There's more to a nation than its borders. The identity of a nation is shaped through the stories of its people's hardships. Literature, cinema, and music routinely deal with these tales, but it's still rare for video games to tackle them. Rare, but not unheard of. Two groups of creators on the opposite ends of the planet chose games to introduce international audiences to the troubled histories of their countries. Here's how they did it.

Children of the Revolution

The Revolution of 1979 saw Iran’s monarchy of 2500 years overthrown by Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic insurgents, and it changed the lives of millions of Iranians. Among them was 10-year-old Navid Khonsari, who 37 years later would tell the story of the nation’s struggle in 1979 Revolution: Black Friday.

Even if you didn’t play 1979, odds are you’re familiar with some of Khonsari’s work. After being displaced to Canada by the Iranian Revolution and obtaining an education, Khonsari set his sights on breaking into the entertainment industry. He did exactly that by writing a couple of scripts for movies and television, but his career blossomed in a completely different medium: video games.

In the early 2000s, he landed a job at Rockstar where for six years he worked on cinematics for the most of the studio’s output. His resume boasts work on properties like Grand Theft Auto, Max Payne, Midnight Club, The Warriors, Red Dead Revolver, and Manhunt. He even lent his booming voice to a few minor characters in the games he helped make. After leaving Rockstar, Khonsari returned to his first passion of cinema. He directed and produced a couple of documentaries and did some more work on games like Alan Wake and Resident Evil 7: Biohazard, before stumbling on a new career opportunity during his travels back to Iran.

You may be as surprised as I was when Khonsari told me, but gaming is huge in Iran. Iranians love games and due to lack of copyright laws in the country have easy and cheap access to them. Some games resonate with Iranians particularly well. Khonsari remembers conversations he had with Iranian children, whose idea of living in the U.S. was shaped by Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. They imagined America as a place of incredible freedom where people are able to drive around, listen to music they want, grab a bite, and go for a workout afterward. “All these options and choices that you had [in the game] they recognized as freedom and democracy,” Khonsari says.

And for his part, these conversations helped Khonsari recognize the untapped potential of games for telling the stories of real people and real events. Right away he knew he wanted to make a game about genuine world experiences, and he didn’t have to look far for a suitable story to tackle. “It was a combination of trying to see if I could take this powerful tool that is gaming and bring real world stories to it,” Khonsari says. “And also telling a story that's connected deeply to me in order to do a proper job as possible.”

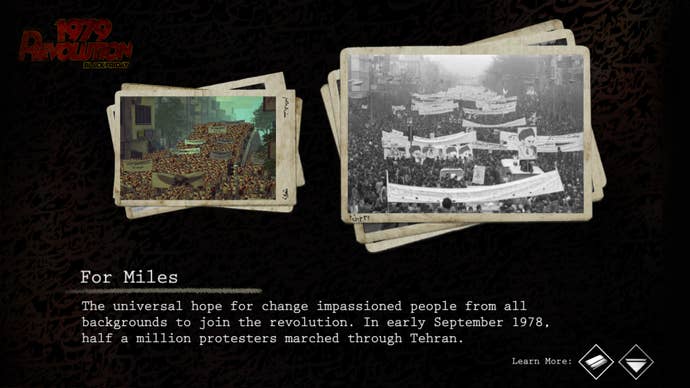

The latter required thorough research. Khonsari and his team at Ink Stories interviewed over 40 witnesses of the revolution from different political backgrounds and referenced photos taken in 1979 on the streets of Tehran by photojournalist Michel Setboun. They retained services of religious and political advisors and academics, obtained recordings of Ayatollah Khomeini and Mohammad Reza Shah (the monarch toppled in 1979), and supplemented all that with home videos shot by Khonsari’s grandfather. And then, to top it all off, recorded all the motion capture sessions with either survivors or children of the survivors of the tragic events.

Khonsari uses the word excessive to describe the research, but it all served a purpose of making the game as accurate as possible. “I was trying to make sure that whatever I do in the end is truthful and honest to the people that we interviewed and the story that we wanted to tell,” he says. The proper preparation also helped alleviate the pressure of telling a personal story that is also universal to millions of people. “That took off any concerns that I had in terms of the representation of an entire nation and what took place in that pivotal moment."

This much source material could have proved detrimental, if it was handled by incapable hands. Khonsari warns about a delicate balance between historical accuracy and creating a fun experience. Too much focus on the gameplay mechanics associated with a certain genre, be it FPS or platformer, makes it harder to stay true to the facts. On the flipside, a misguided push to depict every aspect and every side of a historical event can ruin the game’s prospects of being fun and unique. Ink Stories reverse engineered that dilemma. “We took a look at our story and recognized that it works perfect for choose your own adventure and then surrounded it with cultural and historical aspects,” he says. The studio then put its own twist on the genre by injecting it with influences from the world of documentaries and TV that helped shape 1979’s episodic formula.

Khonsari was also wary of making the game too political and agenda-driven. “There is a continual push to show how unique you are as an individual and how you should have your own voice,” he says. “And that’s wonderful, but on the flipside of that is an agenda where us being different from one another is being used as a way to polarize us.”

In an effort to remain nonpartisan, 1979 follows the story of an 18-year-old aspiring photographer Reza, who is trying to document and understand the events tearing the nation in half, all while facing some hard choices and tests of loyalty to loved ones on both sides of the conflict. “The idea was actually to take something you think is so distant and so foreign,” Khonsari says. “And make it understandable and common enough that you can find it relatable to you and the experiences that you’ve had in your life.”

1979 pulled off the tricky balancing act between telling a real story of Iran and not alienating foreign audiences. Khonsari tells me that the game sold as well as Ink Stories had hoped it would, although few traditional publishers would consider it hugely successful by their standards. After all, the shelf lives for indie games and AAA titles are as different as they come. While AAA games aim to shift as many copies as possible on release, indies continue to sell at a steadier pace for years, albeit with some occasional spikes. In the case of 1979, some of these spikes happen when the new semesters begin at schools and teachers pick up copies of the game for their classrooms. Later this year should mark another spike when the game releases for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One.

And while it’s impossible to track 1979’s sales in Iran, the game was received well there. “I think for the Iranian community to see themselves as lead characters and not playing a terrorist or the bad guys was unique and refreshing and needed,” Khonsari says. The Iranian government, however, didn’t share this enthusiasm. The game was banned in Iran just two weeks after its release in 2016. Ink Stories quickly came up with a solution. “We then made the game in Farsi and put it out there for free, so everyone in Iran could have it.”

As smart and noble as that solution was, it didn’t help Khonsari’s footing with the government of Iran. “I basically can’t go back to Iran right now,” he says. “There’s really no specific rule of law in Iran in terms of why I would be arrested, but as we’ve seen, they don’t have a great record of arresting people without any causes. We’ve seen that a fair amount with journalists. I’ve been advised not to travel back.”

I get a feeling that Khonsari accepted this risk when he set out to make 1979. In an effort to tell a story of his nation, he had no choice but to go all in. Even if it meant personal problems. “I knew I had to be truthful. That the only way to do it would be to be truthful and honest in its depiction,” he says. That gamble paid off and 1979 put him in a position to bring more real-world experiences to light.

Ink Stories and Khonsari continue to tell stories they find meaningful. Its episodic VR homage to Hitchcock's Rear Window called Fire Escape hits close to home for the Western audiences, letting us embrace our voyeuristic urges in Brooklyn. Hero, on the other hand, is, much like 1979, a story of regular people caught in hellish circumstances. This 20x30 foot VR exhibit lets you walk around, touch, and smell a Syrian street before it asks you to save a child’s life. “We ask people to really understand why there are refugees and why they’re running away from a place that’s being bombed,” Khonsari says. The project has been well received at the Sundance and Tribeca Film Festivals, will be presented to the members of the General Assembly at the UN, and the studio is in talks to make it to the Congress and the World Economic Forum in Davos next.

But in its expansion to interactive experiences (and also to TV, through a show in development), Ink Stories is not moving away from traditional video games and its next project is gestating in secrecy. What exactly is it? They wouldn’t say, but for now, Khonsari and his team embrace the luxury to let “the story dictate how it should be told.”

Martial Law

Around the time Navid Khonsari was working on his story of Iran’s struggle, a group of Taiwanese developers did the same for their country. Detention was born as a simple prototype of a 2D side-scrolling horror by Taiwanese independent developer Coffee Yao. As the prototype’s prospects for becoming a real game grew, he found five like-minded creators and co-founded Red Candle Games. The group grew to eight people to ship Detention and now, a year and a half later, 12 people work in the studio’s office in Taipei.

Tiff Liu, the team’s spokesperson, tells me that Detention was born out of under-representation of Taiwanese culture in games. The team decided to be the change they want to see in the world and tinkered away with ideas for Detention. Some of the ideas they stumbled upon reshaped their perspective on what the game could represent. Detention was originally set in a fictional setting in the 80s, which left its makers wanting something more menacing. What followed was a deep dive into Taiwanese history that unearthed the perfect setup for a horror game: the White Terror.

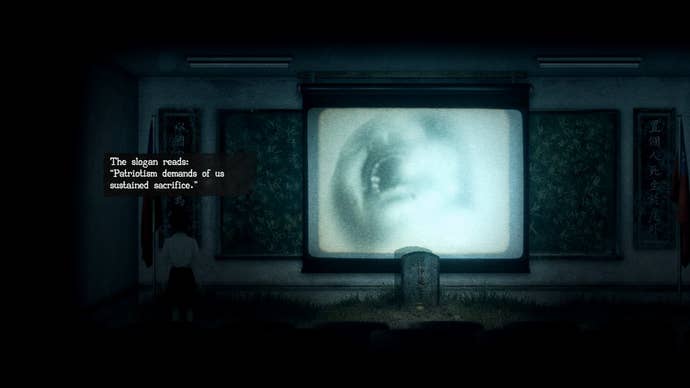

The White Terror was a period of oppression of Taiwanese people by the Nationalist Party of China. Following the violently suppressed anti-government uprising on the 28th of February of 1947, Taiwan went into a state of martial law that lasted for almost 40 years. In the four decades under martial law, Taiwan plunged into an atmosphere of paranoia and mutual surveillance. Red Candle Games noticed that “the fear coming from the extreme oppressiveness could help create the psychological horror environment for the game.”

Liu admits that no one at the studio lived through this, as the oppression ended in 1987 when the dictatorship enforcing it collapsed. Surprisingly, considering it loomed over the country for nearly 40 years, The White Terror is seldom mentioned in Taiwanese schools. “Younger generations aren’t quite familiar with this part of the history,” she says. But the older generations are keeping the memory of that important time alive. Growing up, young Taiwanese—members of Red Candle Games among them—heard personal stories from their relatives. Those stories, supplemented by thorough research in old newspapers and video footage, gave the team an idea of what living under the regime might have been like.

“In our narrow perspectives, we tried our best to imagine how the environment would have been like in that time,” Liu says. “How the people would have interacted under a high-pressure society and what kind of incidents might have occurred.”

With a setting in place, Red Candle Games looked for horror influences anywhere they could. They mention the usual suspects like Silent Hill, Resident Evil, and Clock Tower games among their inspirations, but also name indie gems like The Cat Lady, Neverending Nightmares, and Lone Survivors. George Orwell’s 1984, unsurprisingly for a dystopian title, makes the list along with a niche movie A Bright Summer Day by Edward Yang and the entirety of Taiwanese New Wave cinema movement. But to make a game representing and embracing the Taiwanese culture, Red Candle Games needed to look for influences elsewhere. It turned out that they were all around them: Taoism and Buddhism, Taiwanese mythology and folklore, Chinese horror literature, and even traditional Asian musical instruments all leave their mark on Detention.

A concern for comprehensibility was applied to the setting. Detention doesn’t tackle the White Terror head on, instead, it uses it as a backdrop to a story of a haunted school in the middle of nowhere. Red Candle Games, very much like its peers at Ink Stories, were wary of taking sides in its take on the White Terror.

“By not giving any conclusion about right or wrong, we hope that players can experience the game through their own perspective,” Liu says. And if they ever tried to convey a message, it was a rather simple one: “No matter who you are, the craving for freedom is the same.”

Something unusual in the world of indie creators happened before Detention was released. After the demo for the game was made public, a local publisher Sharp Point Press approached the studio with an offer to adapt Detention into a novel. “None of us thought that Detention would ever be adapted into different media,” Liu says. The team jumped at the opportunity and the subsequent novel treatment of Detention was penned by Jing Ling.

The studio’s next game, another Taiwan-centric horror titled Devotion, is in the works already. Meanwhile, Detention is available for PC, PlayStation 4 and Nintendo Switch.

Beyond Borders

As different as the stories of its nations and its games are, Ink Stories and Red Candle Games have one thing in common: they both had a real impact on people in and outside of the countries they represent.

“[People] come out of it not only having played a great game but feeling that they’ve walked away having a much deeper understanding for a part of history that, especially if you live in the West, still has an impact today,” Khonsari says about the 1979’s reception.

And the team behind Detention hits a similar note when talking about feedback from their customers. “Some told us that they got to know about Taiwan with our game, and others even became intrigued and did their own research about White Terror,” Liu says. “We are happy that we managed to break the language and the culture barrier and have a small voice of our own in this ever-changing gaming market.”

Small or big, every voice has a story to tell. Let’s hope more and more of them will be told through games.