How to Be a Pixel Artist... for Shovel Knight

Yacht Club Games' Nick Wozniak talks about the ins-and-outs of creating pixel art.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In our "How To Be" series each week, USgamer talks to members of the industry and asks them about the ins-and-outs of their current jobs. Find out how they joined the industry, the tools they use each day, and why their jobs are important. These industry members also give potential developers tips on how to reach the same position!

Today, we're joined by Yacht Club Games' Boatswain and Artmancer Nick Wozniak, one of the many fine developers on the Kickstarted 8-bit homage Shovel Knight. Wozniak is an accomplished pixel artist, having learned his craft during his nearly five years as assistant director at Wayforward. Wozniak has crafted Shovel Knight's 8-bit style art dot-by-painstaking-dot.

USgamer: So what do you currently do at Yacht Club Games?

Nick Wozniak: Everything that isn't programming or music! It's hard nail down what I do into a specific title, but my business card says Boatswain: in keeping with the nautical theme of the company, a boatswain is a position on a ship that varied depending on the ship's needs. Another of my favorite titles that some find more relatable (for some reason) is Artmancer. I animate, create pixel models, help design enemies and bosses, do mockups for events in game, help with concept art a little bit, organize the technical side of art, find/work with contractors for animation and generally just make assets. For Shovel Knight, I've been really focusing on the pixels.

USG: How did you enter the industry? Did you have any formal training?

Nick Wozniak: I entered the industry as an animator doing Flash animation for a game that was being developed at Wayforward at the time. I was still going to school working towards my bachelors in computer animation and once I was finished with that, I moved to full-time work with Wayforward. Although by that time, I was doing something very different with the art of a whole other game. Eventually, I found my way to pixel animation and really learned the craft there while managing animators far more talented than I and learning from them in the process.

USG: The common perception of pixel art is you put some dots down on-screen in a vaguely character-like shape and you're good to go. How much planning and effort go into it?

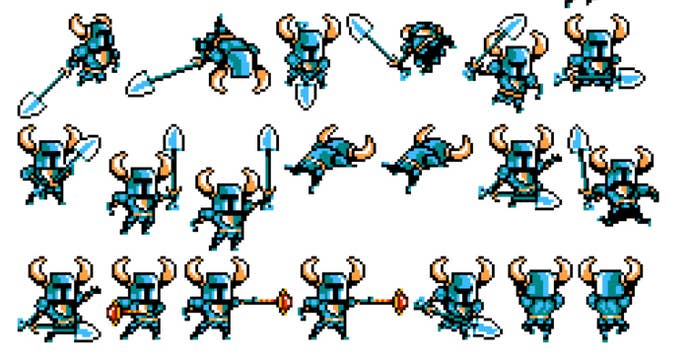

Nick Wozniak: While small on screen, pixel art is a very intentional art where the placement of a single pixel can make all the difference. That sounds like an exaggeration to say "a single pixel", but it's not. Especially when working with small sprites, a single pixel can make the difference of whether or not a character has a face or just a jumble of colors at the top of its neck.

USG: Do you feel pixel art is more or less difficult than the 3D modelling that most of the mainstream industry does?

Nick Wozniak: I've worked with both and I can say that in some ways pixel art is more difficult. It's a mindset that the typical artist isn't used to getting themselves into and the true masters of pixel art do things with pixels that you wouldn't believe. However, in other ways 3D art is more difficult; you can't cut any corners with the details and you can't fake anything. For example, making a bat's wings transition from flying to being wrapped around itself as the bat sleeps is one of the most difficult things to set up in 3D, but is relatively simple in pixels. Each method has its own challenges and advantages; personally, I prefer pixels.

Pixel art is a very intentional art where the placement of a single pixel can make all the difference.

USG: Are there any issues in character creation or animation with pixel art that don't crop up in 3D modelling?

Nick Wozniak: For modelling a character in pixels, you often have to make strange decisions when creating the face of the character, for example. Faces have always been hard to communicate well. Especially if the character is turning their head in any way. In 3D, it's simple for your mind to accept the visuals of a 3D head looking up, even if it is far away, but in pixels you have to do all kinds of tricks to make the eye think that the head isn't distorting or that the face isn't melting.

As for the animation side? A friend of mine once said that pixel animation is the most pure of all animation. This is coming from a guy who has a lot of experience in high-detail line animation, 3D animation, pencil-on-paper animation, and - of course - pixel animation. I tend to agree with his sentiments; the reason being, working in pixel animation is all about working with the form of the thing you are animating. Since everything with pixels is so limited you don't really have the chance to be bogged down with fine grain details and you can focus on the general feel of the character, the motion of the movement, and the volume of the forms.

Despite all that, the issues that I typically deal with are ones of clarity in the poses and rigidness in their movements. The clarity of a pixel model is always a trick of the eye and clever placement of pixels, but in 3D you have a lot more freedom to sculpt and organically create the forms you are trying to communicate. In 3D animation, slow steady movement over time is pretty easy, but in pixels, it can be very difficult to effectively do slow, subtle movement.

Like I mentioned before, both have their disadvantages as well as their advantages, but I get a feeling of great joy when I'm able to naturally move a character in pixels. It's a feeling almost like I figured out the answer to a difficult puzzle or solved a daunting equation.

USG: Is your work purely digital, or do you begin with sketches of some sort?

Nick Wozniak: Primarily my workflow is totally digital, but when working on a pixel model I don't do it from scratch. The model is typically sketched by our character artist and afterwards, I'll take it and make a pixel version in the style of our game. Sometimes details change: things are removed or added, or entire shapes are tweaked. In the example of Plague Knight, I thought he might look cool holding a cane, so I put it in there and it stuck! Now, as you can see in the full illustrated version, the cane is prominently featured.

USG: What's an average working day like for you?

Nick Wozniak: When I'm in full production mode, most days start with a new task. If it's an animation set I need to do, I'll double check with [Yacht Club Games captain/lead designer Sean Velasco] over the design of the character and then just whip up some roughs. Once completed, we either put the roughs in-game to try them out, or I take a pass at finalizing them. After that, they go in-game and if they need revisions we'll take a crack at changing up whatever is needed. It's a very organic approach, but so far it's been pretty effective!

USG: Is there any chance to reuse finished animations and concepts that just don't work?

Nick Wozniak: Occasionally, we do find use for something that didn't make it into the final game. The shopkeeper in the shop mockup we made is a good example of that. However, we like to keep things as agile as possible and make sure we aren't afraid to throw away whole enemy sets that don't work in game. We approach things gameplay first and if something doesn't fit in, even if it's an amazing piece of pixel art, it won't make it in game.

USG: You're not as bound by some of the same constraints as your predecessors, like storage and memory space. Since those issues aren't as pressing, do you find you have more freedom in the creation process?

The desire to make games is a strong part of their blood and so is a youthful attachment to pixel art; it's very natural that those two concepts would converge now that they have the opportunity to.

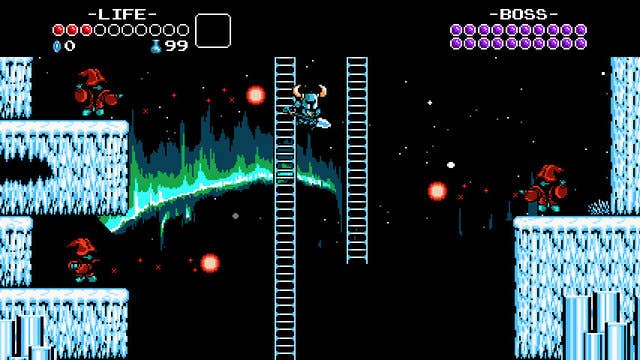

Nick Wozniak: There's a lot of freedom when it comes to current-gen platforms and making pixel art, especially since we don't have to worry about things like making sure the character fits in a 8x8 square, or that we don't exceed 16 colors in total on screen, or that not too many sprites are in the same scanlines. I'm sure our predecessors would be very jealous if, while they were developing those classic NES games, they didn't have to worry about the limitations of the hardware. It's actually something I rarely have to even think about!

The temptation arises, though, to have too many sprites on-screen without reason. When working with those restraints of the past, they really had to make sure that each enemy was placed well and meaningfully. It's possible that working within those restrictions was the best thing for the game as a whole. In light of that, we are trying to make sure that the "freedom" of the modern age doesn't affect our game negatively.

USG: Pixel art is a discipline that tapered off as the 3D era of gaming began. With the rise of the indie developer, digital distribution, and crowdfunding, do you see room for more pixel artists in gaming?

Nick Wozniak: Absolutely! At this time, more than any other that I can remember, it's very attainable for a group of like-minded people or even individuals to make games that follow their own visions. Since they aren't bound by what the publisher demands of them, the choice of art style can be made completely based on the whim of the developer, for better or worse! We've already seen a lot of new takes on the pixel genre in the Indie game-space with games like Cave Story, Super Crate Box, Mercenary Kings, Fez, Mutant Mudds, Volgar the Viking, Swords and Sworcery, Two Brothers, Shovel Knight... the list goes on and on, and I wouldn't expect it to stop! Pixel art is a skill picked up by those who grew up playing their NES, SNES, Sega Genesis, etc. The desire to make games is a strong part of their blood and so is a youthful attachment to pixel art; it's very natural that those two concepts would converge now that they have the opportunity to!

USG: What was the greatest misconception you personally dealt with when you first started doing pixel art?

Nick Wozniak: People think it's easy! A lot of times people will compare pixel games to rom-hacks and claim that pixel games are way over budgeted. What they don't realize is it may be possible to make games that look similar, but games like this do take a lot of money to make well. A lot of time has to be put into making sure the game feels correct, looks authentic, and still adds something to the mix that is new and relevant to the current game-space. Speaking as a developer of a pixel game, we are a group of half-a-dozen core team members working full-time on the project. Just because it's an 8-bit style game, doesn't mean creating engaging, dynamic, and well-designed levels takes any less time.

USG: What techniques should aspiring pixel artists work on?

Nick Wozniak: Learning different dithering styles and getting a good eye for palettes are both great techniques to learn. My favorite thing to do when trying to learn a new concept is to look at someone who has already mastered the techniques I'm learning and copy them as much as possible. Not necessarily copying their work pixel by pixel, but instead creating a character that could shake hands with theirs or live in the world that they've created. If you are looking for a great character pixel master, try checking out the amazing work of Yuriy Gusev (goes by Fool online). If you are looking for great background art, look at Henk Nieborg's amazing tilesets and get lost in their ability to tile forever! There's lots of really great work out there and lots of lessons to be learned from those that have come before you; pay attention to the details and above all else, keep making pixel art!

Shovel Knight is coming to PC, Wii U, and 3DS later this year.

This article was originally published at GamesIndustry International. Those looking to get into the industry can take a look at GamesIndustry International's Jobs Board.