How Journals Are Bringing Humanity to Video Games

The developers behind Life Is Strange 2 and What Remains of Edith Finch share why their characters have an affinity for analog journals.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

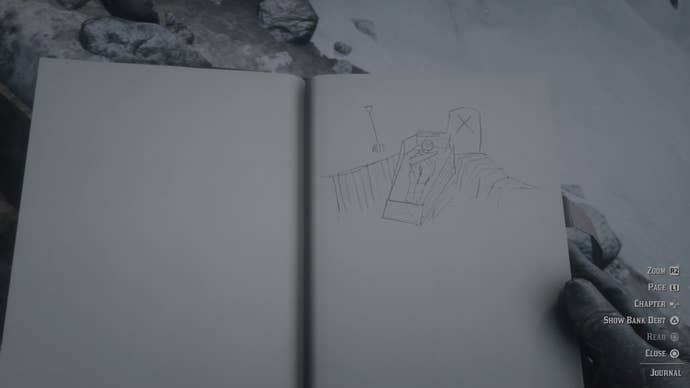

Nathan Drake pauses for a moment to sketch the symbols etched in the mossy stones of an ancient dais. A chapter in the Van der Linde gang’s story comes to an explosive end, and Arthur Morgan stops by a quiet brook to jot his thoughts on the violence surrounding him. Sean Diaz sits by a tree and draws the forest, a necessary break as he tries to figure out how to keep his kid brother safe on their journey through the wilderness.

In a world dominated by the digital, video game characters have increasingly turned to an analog outlet to record their thoughts. While audiologs and emails are popular ways to communicate the thoughts of others, developers are frequently turning to ink and paper to let us inside the minds of the characters we inhabit.

Developers, like the rest of us, turn to journals for various reasons. While bound leather and paper may be an increasingly outdated outlet for reflection (or one that has, at least, evolved to keep up with our fast-paced and influencer-driven age), it remains a powerful symbol in games.

The History of Journaling

In her 1977 book, The New Diary, Tristine Rainer traces the oldest diaries—those not strictly written as historical record—to tenth century Japan, where women of the royal court kept journals as a means of "personal expression that explored subjective fantasies and fiction, not just external realities."

Around the same time in the West, Rainer notes that diary writing was being practiced by witches in medieval Europe and England. "If a witch's diary were discovered, not only would the book be burned,” Rainer writes, "its writer might be burned as well." As a result, she speculates that the long-standing sentiment of taboo and secrecy surrounding the practice today may be vestigial shame, left over from these dangerous roots.

That shame may also be traceable back to the journal's use by the English and American Puritans as a place to confess their sins and keep a watchful eye on their day-to-day activities, vices, and virtues. Diary keeping was practiced outside of Puritan circles, as well. John Wesley kept extensive journals, as did transcendentalist thinkers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

However, Rainer notes that journaling had its own "independent tradition throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries" among European and American woman. By her accounting, the stereotype that diary writing is primarily a woman's hobby is the result of the hobby being widely adopted by eighteenth-century pioneer women.

This presupposition led to the widespread marketing of journals with a toy lock and key to young girls in the 1950s. Today, journals are marketed to both men and women, and their online equivalents—blogs, bujo (bullet journals), Tumblr posts and Twitter threads—are used by people of all genders.

The Diary of Games

However, in the internet age, something fundamental about our approach to writing a journal has changed.

"The diary is the only form of writing that encourages total freedom of expression. Because of its very private nature, it has remained immune to any formal rules of content, structure, or style," Rainer writes in The New Diary. "As a result the diary can come closest to reproducing how people really think and how consciousness evolves."

This isn't true of video game journals, just as it isn’t true of blogs and Instagrammed bujos. These were, after all, written with an audience in mind. However, a journaling mechanic still provides an opportunity for the player to gain insight into the emotional state of their avatar. This is especially welcome in a medium where the standard protagonist has often been stoic, and even, frequently, completely silent.

While on the surface, Red Dead Redemption 2's Arthur Morgan fits the trope of the stoic antihero, his well-worn journal reveals a rich inner life. As he struggles with the brutality that his gang (and he himself) inflict on the world, the journal—always only a button press away—charts the course of his misgivings. When another, less eloquent character borrows Arthur's diary late in the game, their unique approaches to writing illustrate fundamental differences in their personalities.

According to Anaïs Nin, an influential proponent of diary writing in the 20th century and a founder of the "New Diary" movement, "An inner life, cultivated, nourished, is a well of strength, the inner structure we need to resist outer catastrophes and errors and injustices." The journal, then, is as fitting a tool for the video game protagonist as the gun or the sword; a tool designed not to do violence but to cope with the violence one inflicts or receives. While games like BioShock and Spec Ops: The Line have played "gotcha!" with players for killing when killing was the only viable option, Arthur’s journal in Red Dead Redemption 2 allows developer Rockstar Games to inject its story with a feeling of melancholy moral ambiguity without attempting to make the player feel guilty for following the path the designers laid out.

"When I played Red Dead Redemption 2, I really loved what they did with the diary," said Life Is Strange and Life Is Strange 2 co-creative director Michael Koch. "It's a bit like what we're doing with Sean's diary [in Life Is Strange 2], but their game is so huge, it has hundreds of pages when you're nearing the completion of the game, and it tells the player a lot about the characters. I love what they did because Arthur Morgan is a quiet character with difficulties to express his feelings, and if you read his diary, you learn a lot about him. I think it helped me really love this character even more when I read everything he did write in his diary."

This isn't the only approach to journaling, however. While Arthur and Sean turn to their notebooks to express themselves in words and sketches, other games entrust the writing to a non-player character. For example, Kratos, the surly protagonist of God of War, would be unlikely to write at length about his thoughts and feelings. His son Atreus, however, is curious, bright, and talkative. As a result, all of God of War's lore is recorded in a journal written in Atreus' voice. It's a neat trick: as Kratos' smart, but naive, son learns about the world beyond the magical borders of their home, we as the player are also learning.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt uses a similar trick, offloading journaling to someone more prone to self-expression than the protagonist. While CD Projekt Red's Geralt isn't as grunty as Kratos, he's a practical man who cares about killing strygas and collecting crowns. So, The Witcher 3 assigns this reflection to the White Wolf's close friend Dandelion, an outspoken bard. As a result, the player gets reams of lore written in an interesting voice, while maintaining the integrity of the lead character.

For Koch, the protagonist's personality, interests and abilities are important factors when considering incorporating a journaling mechanic.

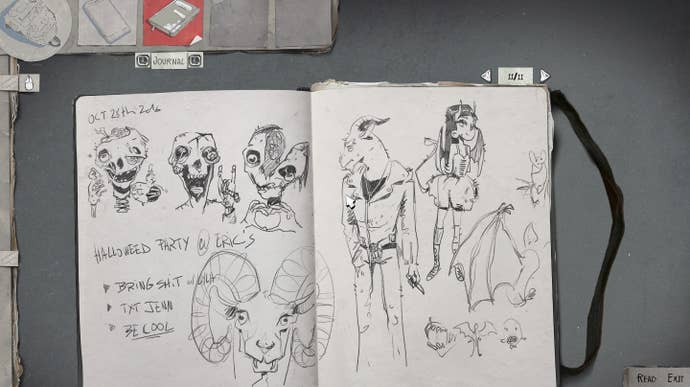

"Of course, it depends on the game you are making and what you want the player to experience. I don't see a type of game where it wouldn't make sense at all, but it all depends on who your main character is. In Life is Strange, we decided to have Max liking to write a journal, while in Life is Strange 2, we have Sean who is an aspiring comic artist, so it’s really in their characterization," Koch said.

"They like to draw, to write, they are introverts who want to put their thoughts or drawings on paper. So, it works for them and it's the way we like to characterize our main characters. It wouldn't make sense if Sean wasn't into drawing at all or we maybe we wouldn't have had a journal for him... For me what is important is that it is linked to the character and the story, to the narrative of the game."

The Journal as an Artifact

What Remains of Edith Finch begins with a shot of a journal, and the rest of the game takes place in the narrative contained within that book, as Edith reads the stories of her brothers and sisters, great-grandmother and reclusive uncle. Giant Sparrow's sophomore effort is a Russian nesting doll of family myths, communicated via ink-smeared journal pages, yes, but also in divorce filings and comic books.

For Ian Dallas— creative director of What Remains of Edith Finch and Giant Sparrow’s first game, paint-throwing sim The Unfinished Swan— journals are a way to bring humanity into a digital medium.

"By their nature, games are a collection of bits and everything in the world is made up of triangles and there's this mathematic—sort of crystalline—precision to the way that most game systems work and are operated with. They tend to fracture uncleanly and unpleasantly, they don't wear in the way that, you know, a natural leather might over time," Dallas said.

"And so, we're always looking for ways to add a little bit of the sense of a person that is creating this and experiencing it and seeing the world. So, having journals was a way to put the stink of the human onto those experiences where, as a physical object, the journal tells you a little about the person who acquired and used this thing."

For Dallas, the journal serves a mechanical purpose, to be sure, but it also serves a metaphorical purpose. It's an object with "psychic weight," something that the humans who own them may feel an outsized emotional connection to. For this reason, Dallas suspects the journal’s usefulness as a symbol will outlive its practical usage.

"In some ways the journal as an artifact in a narrative feels a lot like the record scratch as a sound effect in a film," he said. "It's this thing that is no longer part of our lives but is such a great description for a thing that we care about, and that we often want to reference, that I suspect that it will outlive its appearance in the real world. People will stop seeing journals in the way that they’ve stopped seeing record players in the world, but they will continue to experience them in their fiction."

The journal, then, is a narrative record scratch, a symbol from a vanishing era that still resonates. Thoughts may migrate to Twitter threads, blogs, podcasts, YouTube videos, Twitch streams and other newer means of expression, but the journal will remain effective as a window into a character's mind and as a symbol of their humanity, even in a medium composed of polygons and pixels.