How Dragon Quest Inspired the First Big Console RPG Boom in Japan, Both For Better and For Worse

HISTORY OF RPGS | A survey of the innovative RPGs to emerge in Loto's wake.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This is the fifth entry in an ongoing series by Retronauts co-host Jeremy Parish exploring the evolution of the role-playing genre, often with insights from the people who created the games that defined the medium.

The Japanese public latched onto Dragon Quest in a major way… but not quite immediately. The series’ 1986 debut for Nintendo’s Family Computer saw, at best, mild interest from consumers at first. The series didn't fully pick up steam until, well, it was a series. Publisher Enix realized it could build hype for 1987's sequel, Dragon Quest II, by leveraging its relationship with popular weekly comics magazine Shonen Jump—the publication, not coincidentally, where Dragon Quest illustrator Akira Toriyama's wildly popular Dragon Ball comic appeared. The in-magazine promotions are said to have pushed Dragon Quest over the tipping point, turning the series into a genuine sensation.

By the time Dragon Quest III debuted in early 1988, the series had reached the status of genuine phenomenon. It ranked as Japan's biggest video game hit since Space Invaders. Indeed, such was the enthusiasm for Dragon Quest III that even Americans heard about it, despite the fact that the first of the Dragon Quest games had yet to make their way to the west by that point. Western publications like Nintendo Power giddily reported on the lengthy queues that formed around Tokyo as eager kids (and their parents) lined up to score a cartridge on launch day. Rumors began to circulate that Dragon Quest had become so popular that the Japanese government had to outlaw sales of the series on weekdays. RPG mania was real, and strong.

And where there are video game sales, there are eager imitators. Dozens of developers and publishers scrambled to rush their own takes on the Dragon Quest concept out the door. With the arrival of Dragon Quest III, the console role-playing market could claim to have a representative that stood toe-to-toe with computer RPGs; its massive world and complex character-building mechanics made for a deep and substantial interpretation of the genre. Sadly, only a handful of the console RPGs to hit Japan in the immediate wake of Dragon Quest's rise to fame merit remembering. For every 8-bit classic precipitated by Enix's success, there were a dozen or more less inspired efforts.

Certainly Wizardry and Ultima had seen their fair share of imitators throughout the ’80s. Wizardry in particular had provided a popular format to imitate; duplicate renditions of its first-person dungeon exploration and unforgivingly difficult combat were ubiquitous at the time. However, the numbers of Wizardry clones to appear were like nothing compared to the explosion of Dragon Quest imitators to hit the Famicom and other consoles in the Japanese market during the late ’80s and early ’90s. Dozens upon dozens of attempts to imitate Chunsoft’s groundbreaking creation sprang up in just a few short years. Few of these impersonators left any question about the debt they owed to Dragon Quest. The overwhelming majority of these games copied structure of the original game and its sequels, along with their visual style, and even their arrangement of on-screen interface windows.

Dragon Quest clones proved to be an especially popular avenue for licensed games. Perhaps it was inevitable, thanks to the Dragon Ball connection, but publishers whose catalogs revolved around cartoon and comic properties went to town on turn-based role-playing. Everything from robot space opera Gundam to romantic comedy Ranma 1/2 to post-apocalyptic combat saga Fist of the North Star saw one or more video game tie-ins built specifically in the 8-bit Dragon Quest style. Giant mech suits, funny mascot characters, hyper-violent martial arts experts, candy mascots, and time-traveling giant cats alike could all shrink down neatly into the squat, miniature avatars that populated Japan’s role-playing odysseys. Even unrelated game franchises tried their hand at the genre, too, as seen in the third entry of Jaleco’s Jajamaru-kun series, which had begun life as a simple arcade platformer.

Some of the absolute worst games ever to ship for Nintendo systems emerged from the post-Dragon Quest scrum. Due to differences in timing and logistics between regions, the Japanese Famicom library tended to be far more of an anything-goes free-for-all than the tightly controlled American NES business; the dregs of the Famicom market are far more dreadful than even the absolute worst NES fare. RPGs, a complex genre even on 8-bit hardware, tended not to mesh well with the borderline-amateur developers who sprang up during the Famicom boom. Efforts like Super Monkey Daibouken (VAP’s incompetent take on the Journey to the West legend) or Stargazer (Another’s futuristic-themed RPG that appears to operate without any sense of internal logic), both resemble Dragon Quest in many respects. Yet,quality is not among them. These disasters have gone down in history not only as some of the worst RPGs ever, but arguably as some of the worst games, period.

It’s this era of gaming that Retro Game Challenge, Bandai Namco’s DS tie-in with popular television series Game Center CX, attempted to capture with its mini-RPG segment Guadia Quest. For anyone who remembers Famicom gaming circa 1987, Guadia Quest is a mostly authentic parody of the Dragon Quest clones that appeared in such prolific numbers during that era. Guadia Quest was obviously not a real retro Famicom RPG, because it was actually competent and fun.

That said, companies who tended to produce higher-grade work unsurprisingly put out more impressive variants on the Dragon Quest format. Konami, for example, created a slick sci-fi adventure called Lagrange Point. Powered by a custom-built chip that (among other features) enabled arcade-quality FM synthesis audio, Lagrange Point is arguably the technological high-water mark for the Famicom. More modest in design, though not in influence, was Capcom's Sweet Home. A horror-themed role-playing game set in a haunted mansion, Sweet Home served as direct inspiration for the original Resident Evil a few years later. And Nintendo themselves, with the help of writer Shigesato Itoi, turned Dragon Quest’s format inside-out with the metatextual Mother, a.k.a. EarthBound Zero.

And while direct Dragon Quest imitators appeared in staggering quantities, a few console developers managed to look beyond Enix’s best-selling venture for inspiration. The best RPGs to emerge from Japan’s RPG boom used Enix's hit not as a holy text but rather as a prompt. They took advantage of the nation's mania for role-playing as an opportunity to explore the greater limits of the genre. Many of these games reached further back into history, drawing on seminal PC RPGs like Wizardry and Ultima, the same way Dragon Quest had.

By far, the biggest and most successful of Dragon's Quests would-be successors was Final Fantasy. Developed by a small company called Squaresoft, Final Fantasy wouldn't come close to matching sales of Enix's RPG goliath until its seventh installment a decade later (Final Fantasy VII for PlayStation). Nevertheless, it did well enough to justify a succession of sequels, each building on the last while simultaneously striking out in innovative directions.

Designed primarily by a man named Hironobu Sakaguchi and programmed by Apple II legend Nasir Gebelli, Final Fantasy bore little overt resemblance to Dragon Quest. Sure, the overall gameplay flow worked much the same: Players began their adventure by speaking to a king in a castle town, ventured into the larger world, and slogged through an endless succession of random enemy encounters. The similarities more or less ended there, though. In terms of of its overall sensibility as a video game, Final Fantasy fell somewhere between Dragon Quest and Ultima. Its combat system avoided Dragon Quest’s first-person view in favor of a perspective that lined up both parties on opposite sides of the screen. Despite this staging, however, it lacked Ultima's battlefield positioning mechanics. Squaresoft also took inspiration not from older computer RPGs, but rather from the ur-text: Dungeons & Dragons. Even a few of the game’s enemy sprites had to be redrawn and renamed in later releases so as to avoid infringing on original D&D creations like Beholders.

Final Fantasy allowed players to build a party of four warriors, each belonging to one of six different classes that they could mix and match. Mage characters had to purchase spells rather than learning them naturally as they leveled up, and spells were ranked into level powered by "charges" for use rather than drawing mana from a general pool. Unlike Dragon Quest, the game didn't dull the sting of defeat for inexperienced players; a game over was a hard game over rather than a soft reset back to the last save point. In short, it felt like a more serious take on the genre, geared toward older players, than most RPGs on NES and Famicom.

One lesson Final Fantasy did take from Dragon Quest was the importance of memorable enemy visuals. Squaresoft hired anime designer and pop artist Yoshitaka Amano to illustrate both the game's packaging and its in-game monsters. Amano's ethereal, detailed style stood in stark contrast to Toriyama's cartoonish whimsy. Toriyama's slimes were jolly blue teardrops; Amano's were viscous blobs clinging to an unseen ceiling. Toriyama's trolls dressed like Flintstones characters and licked their lips in vrutish glee; Amano's shaggy trolls held their heads, shrieking in rage. Final Fantasy's enemies looked far more impressive than the chubby player characters—especially the main bosses, who took up a large chunk of real estate with their unique sprites.

Final Fantasy's willingness to take itself more seriously than Dragon Quest and that game’s innumerable clones made it deeply unfashionable in Japan, where cute and fun reigned, but it helped the game's fortunes abroad. The series quickly established itself as the premiere console RPG franchise in America—hardly a million-seller, but far more popular than competing console RPGs. On top of that, Squaresoft's willingness to experiment with mechanics and tone made Final Fantasy a rich source for spin-off franchises. The original Final Fantasy debuted in Japan in 1987, and within five years, the series had no less than three distinct spinoffs. Final Fantasy Mystic Quest offered a simplified take on RPG mechanics to ease beginners (specifically, inexperienced American players) into the genre; SaGa, also called Final Fantasy Legend, took the opposite tack, emphasizing esoteric mechanics and open-ended play; and Seiken Densetsu, or Final Fantasy Adventure, grafted Final Fantasy mechanics onto the action-RPG style of The Legend of Zelda.

Over on the Sega side of the burgeoning console wars, Final Fantasy arrived day-and-date with an equally high-minded competitor in the form of Phantasy Star for Master System (or Mark III in Japan). Where Final Fantasy combined Dragon Quest with elements of Ultima's sequel, Sega looked primarily to the very first Ultima and Wizardry, combining its top-down town and world views with first-person dungeons and battle sequences. Unlike Squaresoft and Enix, Sega didn't venture out of house for its creative talent; instead, it worked with internal staff members to develop a distinctly Sega-style role-playing adventure.

One of those team members happened to be future Sonic the Hedgehog co-creator Yuji Naka, whose programming wizardry made Phantasy Star's labyrinths vastly more immersive than the first-person mazes that had appeared on PCs. Not only did Phantasy Star's labyrinths appear in full-screen, full-color glory rather than as stark windowed wireframes, they scrolled and spun smoothly, too. Advanced details like this gave Phantasy Star a distinct edge. Crisp visuals, hard-hitting music, and a science fiction-fantasy theme hearkened back to the freewheeling early days of computer RPGs while simultaneously giving off a sophisticated air that, like Final Fantasy, spoke to an older audience than standard Famicom RPG fare. Fittingly, Phantasy Star's plotline avoided clichéd genre tropes, revolving instead around the heroine’s quest for vengeance. There were no princesses to rescue or mystical treasures to seek in the player’s planet-hopping journey to stop an authoritarian force controlling the solar system.

With the simultaneous arrival of Final Fantasy and Phantasy Star at the end of 1987, console RPGs definitely seemed ready to expand beyond the jolly, kid-friendly fare offered by Dragon Quest. Granted, even Dragon Quest's first sequel had assumed from players a considerable degree of expertise with its outrageously wicked difficult level, but the series' newfound competitors matched stiff challenge with a more teen- and adult-oriented world view. In truth, however, even Final Fantasy had already been beaten to market by the first entry of a franchise that would make Squaresoft's darkest plot twists seem as frivolous as a Dragon Quest "puff puff" by comparison: Namco and Atlus's Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei.

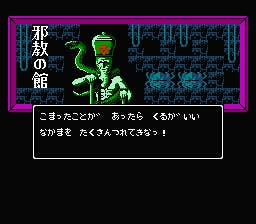

Based on a popular light novel by Aya Nishitani, Megami Tensei hewed even closer to Wizardry than Phantasy Star had. It presented a far less technically impressive take on the first-person dungeon RPG than SEGA's fare, with stilted movement in a cramped, windowed viewpoint. What Megami Tensei lacked in programming prowess, however, it more than made up for with its unique setting and mechanics.

As in the novel that inspired it, Megami Tensei took place in a contemporary version of Tokyo and revolved around the use of personal computers that served as portals through which the protagonists could summon demons. While the heavy emphasis on otherworldly monsters made it an unquestionable work of fiction, Megami Tensei's real-world setting grounded it in a way that was entirely new to Japanese RPG fans in 1987. Furthermore, players only controlled two human party members as they become embroiled in a battle of gods and demons. Their other combatants took the form of demons, who could be persuaded to join the team through battle dialogue trees under the correct circumstances. Demon management involved a number of complex subsystems, including a shifting moon-phase calendar (akin to Ultima III's) that determined the behavior and moods of monsters and a demon-fusion system that allowed players to combine their supernatural allies into stronger forms.

As the 8-bit era began to melt into 16-bit gaming, Japanese console RPGs grew more ambitious in nature. Even as countless publishers churned out dozens of by-the-numbers Dragon Quest clones, others began to explore the potential of marrying role-playing elements to other genres. From SNK's Crystalis to the the likes of ActRaiser and E.V.O.: The Quest for Evolution, hybrid console RPGs found innovative ways to combine stat-crunching and quest-based narratives with radically different styles of play. Japan's console RPG experiments of the ’80s and ’90s could easily justify an entry of this series all their own.

It is, perhaps, redundant to refer to "Japanese console RPGs" of that era; nearly all console RPGs in the late ’80s and ’90s hailed from Japanese studios, while only a handful of the country’s major publishers (most notably Nihon Falcom) targeted PCs at all. Even console ports of American PC games were typically handled by Japanese developers like Infinity and Atelier Double. Role-playing thrived on PCs in the west thanks to tremendous classics like Pools of Radiance and Wasteland. It wouldn’t really be until BioWare's Knights of the Old Republic—released in 2003!—that western RPG designers would fully treat consoles as a priority and begin to play catch-up with nearly two decades of overseas innovation. Which isn't to say that western studios were slacking when it came to RPG innovation, only that they had set their sights almost exclusively on PCs…. as we'll see in our next entry.