How a Parry Saved Street Fighter: 20 Years of 3rd Strike

Everyone loves a comeback.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

It's primal, I think, the rush of witnessing the snatch of victory from the mouth of defeat. One competitor is on the losing side, down to a sliver of themselves. The other side's domination has only produced a gulf to cross, their continued battering of the underdog almost comical. And then by calm control, sheer will, or dumb ass luck, there is a shift almost tectonic, the tables turned. It's the Cavs roaring back from being down 3 games to 1. It's Ali stepping back in the ring after government exile. It's Daigo swatting away 15 kicks before a small, screaming crowd of true believers. We want to believe in comebacks because we want to remember what hope is. We want to see a comeback because, on rare occasion, we get to see what hope can look like.

It's ironic to talk about Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike in those terms. We used to talk about 3rd Strike as an unloved middle child. Now, grown and wise, it's the pinnacle of its form. As the fighting game maxim of "easy to learn and impossible to master" goes, the knowledge that 3rd Strike can practically never be fully mastered makes it a cruel teacher, but its followers love it for that reason alone.

Yes, time has been kind to 3rd Strike. Having been released at perhaps the worst time for a fighting game to come to an arcade, it was unabashedly targeted to the hardest of its hardcore followers. But it's to these people that we thank for keeping the fire lit for so long. The game is in resurgence in competitive circles, and has become revered amongst critics and players as the years have passed. Now on its 20th birthday, we dutifully accept it as one of the all-timers, the masterpiece that it’s always been.

Face Down on the Mat

"The Street Fighter 3 series overall is a strange duck," says former Capcom producer Seth Killian. "It got better with each iteration, and 3rd Strike is the undisputed star of the series, but the core experience always stood far apart from that of the Street Fighter 2 [series], the Alpha series, and of course SF4 and SF5."

Killian isn't wrong. It's hard to follow up a smash like Street Fighter 2 with a proper sequel. Fan expectations and the then-contemporary games media meant enormous pressure for another sea change. By the late 90s, though, 3D fighting games like Tekken and Virtua Fighter were drawing attention away from aging 2-dimensional sprites, and they worked better on home consoles of the time with the muscle to push polygons, giving normal arcade-going fans a reason to stay on their couch. The response from developer Capcom and series producer Tomoshi Sadamoto was to find ways to implement real life fighting mechanics like the 3D fighting games had, but into a world of fireballs and dragon punches. Coming off wrestling games like the Saturday Night Slam Masters series, he felt that new players needed to find a way to deal with corner pressure and impossible situations, which became a guiding principle of the design.

Another was its look. Capcom's internal fighting game divisions were cranking out increasingly beautiful games every year, but a real successor to Street Fighter 2 needed to push limits even beyond that scope. The Street Fighter 3 games animated each characters' 700-1200 frames of art running at 60 frames per second, each frame painstakingly drawn by hand, scanned, and then pixel-corrected by a small team of designers.

Akira "Akiman" Yasuda confirmed recently that Street Fighter 3 didn't begin its life as a proper sequel to its seminal predecessor, only becoming one after his own involvement according to last year's Undisputed Street Fighter coffee table book, and not with a moment to lose. The artistry slowed production, and the game needed to get on arcade floors. New Generation, the first game in the Street Fighter 3 series, was released in 1997 with 10 playable characters, eight of them completely new, and three of them head swaps of each other. It flopped.

Capcom scrambled. Developed for its expensive new compact disk-based CPS-III arcade board, the design team went back to work immediately to fix and add fundamental systems to the game as well as expand the roster. After all, this was still a point where the publisher was cranking out an impressive cascade of other arcade fighters like the Alpha series and the Darkstalkers games, their competition from crosstown Osaka rivals SNK and the aforementioned 3D games notwithstanding. Sinking time and money into a lavishly animated dud needed to be rectified post haste, with players bouncing off New Generation almost immediately with so many other options. Within the year, Capcom cranked out 2nd Impact, giving Street Fighter 3 three new characters and adjusted systems like EX moves and stat-boosting taunts.

But it wasn't enough. Arcades were withering in Europe and the U.S. as home consoles could finally rival standup experiences. Fighting games themselves were becoming esoteric and even unwelcoming to newcomers. Capcom themselves acknowledge this in Undisputed Street Fighter that games outside of the Street Fighter umbrella were only modest successes. One final revision of Street Fighter 3 was commissioned, and this time, the team took their time.

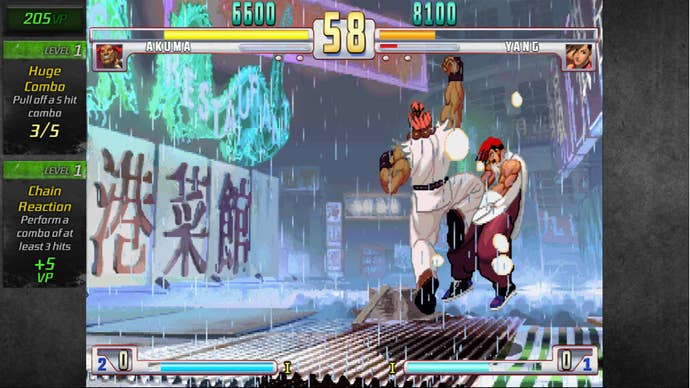

From a glance, it's hard to see how dramatically 3rd Strike improved over 2nd Impact. The differences are mostly subtle but significant, except the roster. The year and a half break between releases gave the team time to add five completely new characters while also dramatically overhauling members of the existing cast like Akuma. That means that while the majority of the development time went to animating new characters, thoughtful adjustments were still made to the underlying DNA of its high level systems, like the parries. But nobody in the West seemed to care. Arcades were effectively death rattling, and many players had written off the SF3 games as tournament draws.

Killian attributes a portion of this to what he calls "local maxima:" finding a basic strategy or playstyle that's adopted by nearly everyone. If you found yourself at a local player gathering, you'll see time and again a Chun-Li or Ken player retreating to a corner to whiff normal moves from a safe distance, which raises their Super meter so they can unload their respective dominant Super Arts. It's a drag to watch, and boredom from players and spectators is a curse for a game's meta. It needed fresher blood than the traditionally strong Southern California and New York City scenes. "LA was one of the strongest early scenes for 3S," Killian says, "and it took Hsien Chang from Austin, Texas to come and kick a bunch of asses until people realized there might be more to discover in the game."

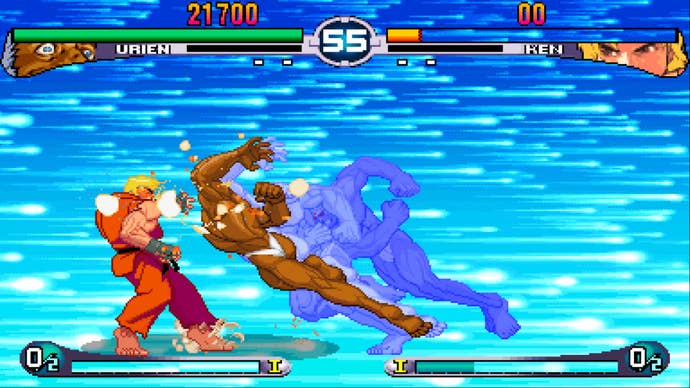

This was a turning point. In Chang's wake, says Killian, a wave of Japanese players arrived for West Coast tournaments and "showed Americans what more was possible—from Mester's early Genei Jin Yun combos to a young (and future Evo champion) Tokido with a stylish and deadly Urien." More character choices and playstyles began to develop, but outside of the cutthroat pay-per-play arcades in Japan, it was slow going. Still, 3rd Strike earned itself a newfound cult on both sides of the Pacific. Conveniently, it happened when it was the only game left in town.

The early 2000s "Dark Age" of fighting games had settled in by this point. Capcom no longer had any interest in producing new Street Fighter sequels, with even franchise founding father Noritaka Funamizu lamenting in 15th anniversary character bible Street Fighter Eternal Challenge that if the series never recovers, at least with 3rd Strike, they went out on the highest note they could.

Then, of course, lightning struck.

West Coast tournament organizers began expanding their scope by 2002 and ultimately, their size; first with Battle By the Bay, then reimagined into the Evolution Fighting Series, eventually evolving into simply Evo. Japanese players that essentially taught many Americans how 3S worked would make a pilgrimage to re-establish their worldwide dominance, legend-in-the-making Daigo Umehara among them. If it took Japan to teach the world how to play 3rd Strike, it took Daigo, however, to remind the world of fighting games' greatness.

Much has been made of the "Daigo Parry," or "Evo Moment #37," in 2004, which Killian shot himself (though other videos of the event have recently surfaced), and for good reason. A single touch away from defeat, Umehara's Ken famously baits and parries all 15 hits of Justin Wong's dominant Chun-Li in a comeback for the ages. In terms of burgeoning esports moments, it was one of the first grand spectacles at a tournament of that scale widely shared online. In regard to the fallout, though, it generated enough renewed grassroots interest in the genre that it lead to larger tournament attendance, which ultimately birthed new games and a genre Renaissance. It's often stated with no small amount of hyperbole that the Daigo Parry saved Street Fighter. Some even say that it saved fighting games as a whole.

"I think if that moment hadn't occurred," says Umehara over email, "things wouldn't be the same now."

From Killian's perspective, "To most of the video's audience, they just filed the highlights under 'Street Fighter,' or maybe 'fighting games,' with little attention to the version being played," noting that even back then, endless Street Fighter sequels and their turbo-charged names were a meme amongst gamers. "For the wider [fighting game community], seeing the reaction to the clip meant realizing that the same electric feeling we were all addicted to could translate to a wider audience. 'Normal' people could get hype about the FGC, even if they didn't understand all the details."

It's still chilling to watch now, 15 years after the fact, especially with the newly unearthed footage capturing the crowd's commentary during the match. Players were trying to coach Wong into playing conservatively at the end, an audible "don't do it!" plea to holster the loaded gun of Chun's usually game-breaking super art. Even onlookers could smell what was coming. It was in the air.

Lest we forget, though, that the Daigo Parry wouldn't be viewed by millions on the internet, have entire books and documentaries made to dissect it, or have Questlove occasionally retweet it, if it weren't a fundamental 3rd Strike moment.

"[3rd Strike] is a very unique game," says fighting game tournament commentator David "UltraDavid" Graham. "It allows for the greatest sense of freedom and control over the opponent, and at the same time, and sometimes even in the same rounds, the most frustrating feeling of not having any options at all. As imbalanced as its characters' options are, [3S] still lets the players play against each other as human beings more directly than any other game. In short," he concludes, "it's the parry."

The Will to Win

There is no better gift the Street Fighter 3 games gave us than such an avenue for amazing comebacks. The parry system, on a macro level, altered the structure of playing a 2D fighting game. No longer were projectiles tossed from mid-screen a crisis of character spacing and bad guessing. No more would a special move inelegantly placed on an opponent chip away their health for a lame win. Parries gave highly skilled players the opportunity to swat away nearly every incoming attack, and often leaving the other player open to free punishment.

On a deeper, almost primal level, though, parries changed the psychology of the game. In a fit of brilliance, Street Fighter 3 series producer Sadamoto originally wanted parries to occur when a player blocked at just the right moment. The design team vetoed the idea, though, and changed the parry input to pressing toward an attack the moment before it lands. This gives parries a significant element of risk and reward. At low health and clinging on for life, for example, a player can guess or bait where attacks are coming from. With enough skill, as Umehara has famously illustrated, comebacks can be as damning as they are flashy. Guess incorrectly or botch the timing, though, and a player is essentially walking into their own defeat. It's genius.

"I think if that moment hadn't occurred, things wouldn't be the same now."

With this system, there are no guaranteed wins. Players that can behave more erratically than their competition tend to have great success, but those that can train their opponent on the fly to bait easily parried attacks rise to the top. 3rd Strike ultimately tuned this system like a symphony violin compared to New Generation and 2nd Impact. Subtle, though significant timing was altered for when incoming attacks could be batted out of the way and jumping parries were unified to a single input for easier use. Its most important addition, though, was the red parry, which gave an opponent blocking attacks a very strict window of time to parry out of block stun. This meant that even tossing out multi-hit super moves wouldn't lock down wins if a player could red parry out of the blocking. Certainly a change aimed at players on the high end of the skill gap, but also poetic beauty for fascinated spectators.

It's hard not to blame Street Fighter 3's early missteps and ultimate slow march to fighting game fondness on such a system. A precision-based approach means that any theoretical skill ceiling for this game is infinite; hypothetically, with enough time and practice, a person may meet an opponent that can literally parry anything they throw out. As time has marched forward, so too have such frame-specific systems become harder to accurately archive now that lag-free CRT televisions are fading into memory, and input delays are inherent to every modern television.

Parries were a part of fighting games before SF 3: New Generation –SNK's Samurai Shodown 2 had a rudimentary system of proper block timing (over time termed "Just Defend") as early as 1994. But the Street Fighter games' smart implementation of the concept and 3rd Strike's refined execution of it is perhaps the greatest part of its legacy, even if it's geared toward the hardcore.

"[Some] recoil in terror, some push through to find the glory on the other side," says Killian. "With all players equally armed with the universal option to 'just parry it!,' even abusive, terrible stuff (unblockables, Makoto 100% combos, Yun's brutal Genei Jin loops, Chun-Li in general) seems like something you can handle, if only you practiced a little harder.

"The parry is such a powerful source of player hope," he says, "that 3rd Strike players can endure seemingly anything. I love it deeply."

The Champ's Legacy

And 3rd Strike has endured. It certainly has for me especially.

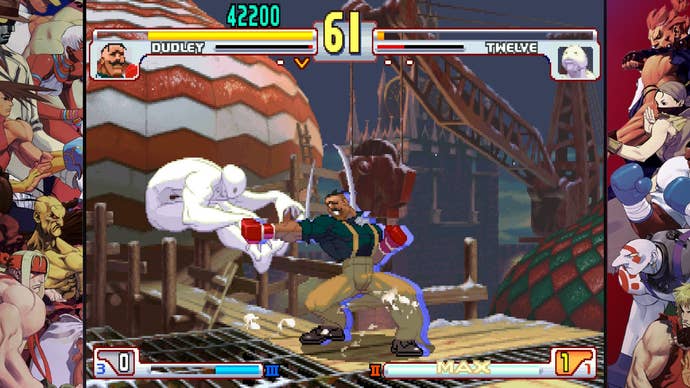

I cannot be objective when describing this game to people, though I acknowledge its many flaws. Oft cited is the game's hideous balance, with Chun-Li, Yun and Ken sitting atop every fan-made tier list for the past 20 years. While in theory the parry system levels the playing field, these characters and some of their specific tactics gnaw at 3rd Strike's critics. Some fans have taken to thoughtfully rebalancing the game themselves, with games industry professional, Skullgirls and Indivisible lead designer Mike Zaimont, even penning his own rebalance manifesto.

Umehara tells me that is just the reality of things, that older games have balancing issues. "The players have accepted that," he says. "That said, I do feel like it might have attracted more players if it had a rebalance."

For his part, Killian at least seems to have broached the topic while still at Capcom for the 3rd Strike Online Edition in 2011. "No rebalancing talk ever went very far," he tells me, "and so my mission was to see a truly faithful reproduction.

"3S is considered to be kind of a holy relic by Capcom Japan—a true study in excellence. Talking about rebalancing is as if you had an idea for a way to improve on saying the rosary—even if you're right, it's beside the point for most devotees."

For myself, our relationship is complicated, this Street Fighter game and me. By 2000 when it hit the Dreamcast in the US, I had already seen how Final our Fantasies could be with polygons and tried to decode the batshit zaniness of Tekken genealogy four times over. I was in college at this point, with no sign of an arcade for miles. But the Street Fighter 3 series of games always held an oddly sinister air about them, as if they seemed to be made for an older crowd than mine, even though I could legally drink when I finally got my hands on them. It is gorgeous and strange, as if Ralph Bakshi made anime, but really loony anime.

I bootlegged it on Dreamcast and then received it as a gift for my PlayStation 2, but I was too busy aggressively flushing my time down a sewer of dozens of subpar JRPGs to really get to know 3rd Strike; I'd play it, but never with the monastic devotion it demanded. But it was with me through my entire adult life looming behind me; a presence forever lingering over my shoulder.

The Daigo Parry struck the match. Capcom made Street Fighter 4 and fighting games were back in the collective nerd gestalt by 2009. In 2011, realizing that they needed to keep making money on these things, the publisher finally updated 3rd Strike for consoles. Okay, I told it, let's finally get to know each other. 3rd Strike took off its glasses and let its hair down. Eight years, several joysticks, a few rereleases, some DIY online services, and hundreds of thousands of matches won and lost by a wakeup parry timing later, it whispered back "what took you so long," like a goddamn Cameron Crowe movie.

To be sure, mine is not a name that will be spoken at tournaments in hushed, reverent tones. I will never fly to Japan to prove my mettle; never go down in history with glorious displays of showman-like comeback gusto (maybe!). I am no chump by most means, but I'm also not willing to live a life of lies. But, by God, I play it enough that I may as well have programmed 3rd Strike myself. A weekly meetup at a local bar with friends. Evenings at home online as my wife and baby sleep. I study YouTube matches several years-old during bored lunch breaks like one would for a state bar exam. I play a lot of video games, but 3rd Strike and I, we got a thing going on. It's devotion, and respect, and pursuit.

I feel as though I owe this game something. I've been floating around the games press as a freelancer since 2009, doing the occasional news story or review, and mostly for free sites. It was inglorious and disheartening. My first story for this very site, though, was a feature about this very game, and it single handedly altered the direction of the games writing I do. It's also why I've been spending the last year breaking the game apart, piece by piece.

I don't use Makoto, but I want to tell people about the brilliance of making a character arguably more effective when she's cornered. I don't listen to a lot of hip-hop anymore, but I can't shut up about how forward thinking it was for Japanese composers and sound programmers to embrace their Western audience with such a soundtrack. I want to play it all the time, even when I'm getting pounded on for hours on end. It annoys people—I annoy people. It is the cross I bear.

I am not alone. While the game doesn't command the tournament numbers it has pre-Street Fighter 4, its status has clearly grown. American expats move to Japan to learn 3S at ultra-high level in arcades that still attract players and neophytes. This year alone, players in the United States have taken up themselves for a grassroots tournament campaign, the Jazzy Circuit, which is part of the draw for many major American tournaments.

Most impressive, and a further testament to 3rd Strike's continued growth, is the Cooperation Cup, a monstrous 5 vs. 5 team tournament in Japan every January, with well over a hundred teams from around the world competing. In 2019, Cooperation Cup enjoyed its 17th annual tournament, with entry growth beating every previous year and streaming numbers (both in Japanese and in English) to match. It's essentially 3rd Strike Christmas. Graham says that he's not sure there's much of a groundswell for the game in terms of new players, but definitely a resurgence in keeping the dedicated 3S scene alive. "Community leaders are doing a great job on that front," he says, "and that's really great to see."

Umehara agrees. "Even now, a certain segment of Street Fighter fans have stuck with it. With anything that unique, games or otherwise," he says, "you tend to get a community passionate enough to sustain a thing's life. I think it will continue to live on as a result." As a frequent Cooperation Cup competitor, he's remained part of that community.

Tonight, I'll have a drink, connect my mangled arcade stick, and throw Denjin Hadoukens. I'll wade through lobbies of players too new to know how to handle my Aegis Reflector bullshit or too old to not punish me for trying. I'll get on social media and moan about Yun. But that's what it is—social. 3rd Strike is still in the conversation at age 20, and I'll do my best to keep it there. I'm a little proud of that. As we get older, birthdays are less about gifts and more about shared experience; people just want to see their friends and family. Every time I play the game, that's what I see.

Happy birthday, Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike.